I’d like to tell you about a little utopian community nestled in some faraway mountains where caffeine is heavily regulated. Everyone is 20 percent prettier than average and owns a modest home outright. There is no divorce or attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder. But this place does not (yet) exist as a model. A few European countries have moved toward regulation—in Sweden, for example, many grocery stores do not sell energy drinks to people under 15. The United States is not likely to lead the charge into federal regulation tomorrow or next year, but when Michael Taylor, deputy commissioner for foods and veterinary medicine at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, was asked last week, “Is it possible that FDA would set age restrictions for purchase?” he responded:

We have to be practical; enforcing age restrictions would be challenging. For me, the more fundamental questions are whether it is appropriate to use foods that may be inherently attractive and accessible to children as the vehicles to deliver the stimulant caffeine, and whether we should place limits on the amount of caffeine in certain products.

Taylor’s comment came in the context of the FDA’s announcement that, as the organization put it, “in response to a trend in which caffeine is being added to a growing number of products, the agency will investigate the safety of caffeine in food products, particularly its effects on children and adolescents.” It’s a kind of nonchalant way to say that the organization in charge of making sure everything we eat and drink is safe for us is, decades into the mass marketing and sale of heavily caffeinated products without regulation to all U.S. markets, going to look into their safety.

The only time the FDA explicitly approved adding caffeine to anything was for use in colas in the 1950s, not long after coca leaves were taken out of soda—after Coke was implicated in a string of rapes. Much as the Second Amendment did not anticipate M45 Quadmount anti-aircraft machine guns, that mid-century caffeine allowance by the FDA was not meant to speak to today’s energy drinks: Red Bull, 5-Hour Energy, Monster, Full Throttle, CHARGE!, Neurogasm, Hardcore Energize Bullet, Facedrink, Eruption, Crakshot, Crave, Crunk, DynaPep, Rage Inferno, SLAP, and Venom Death Adder. Not to mention caffeinated water, gum, lip balm, socks (probably in development), etc.

In January, I asked “How much caffeine before I end up in the E.R.?” That was in response to a report from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (a government behavioral health agency) that called energy drinks “a continuing public health concern” and noted that “energy drink-related” emergency department (ED) visits increased nearly tenfold between 2005 and 2011.

According to Taylor, the FDA’s primary concerns center on the idea that:

Energy drinks’ with caffeine are being aggressively marketed, including to young people. An instant oatmeal on the market boasts that one serving has as much caffeine as a cup of coffee, and then there are similar products, such as a so-called ‘wired’ waffle and ‘wired’ syrup with added caffeine. … The proliferation of these products in the marketplace is very disturbing to us … We have to address the fundamental question of the potential consequences of all these caffeinated products in the food supply to children and to some adults who may be at risk from excess caffeine consumption. We need to better understand caffeine consumption and use patterns and determine what is a safe level for total consumption of caffeine.

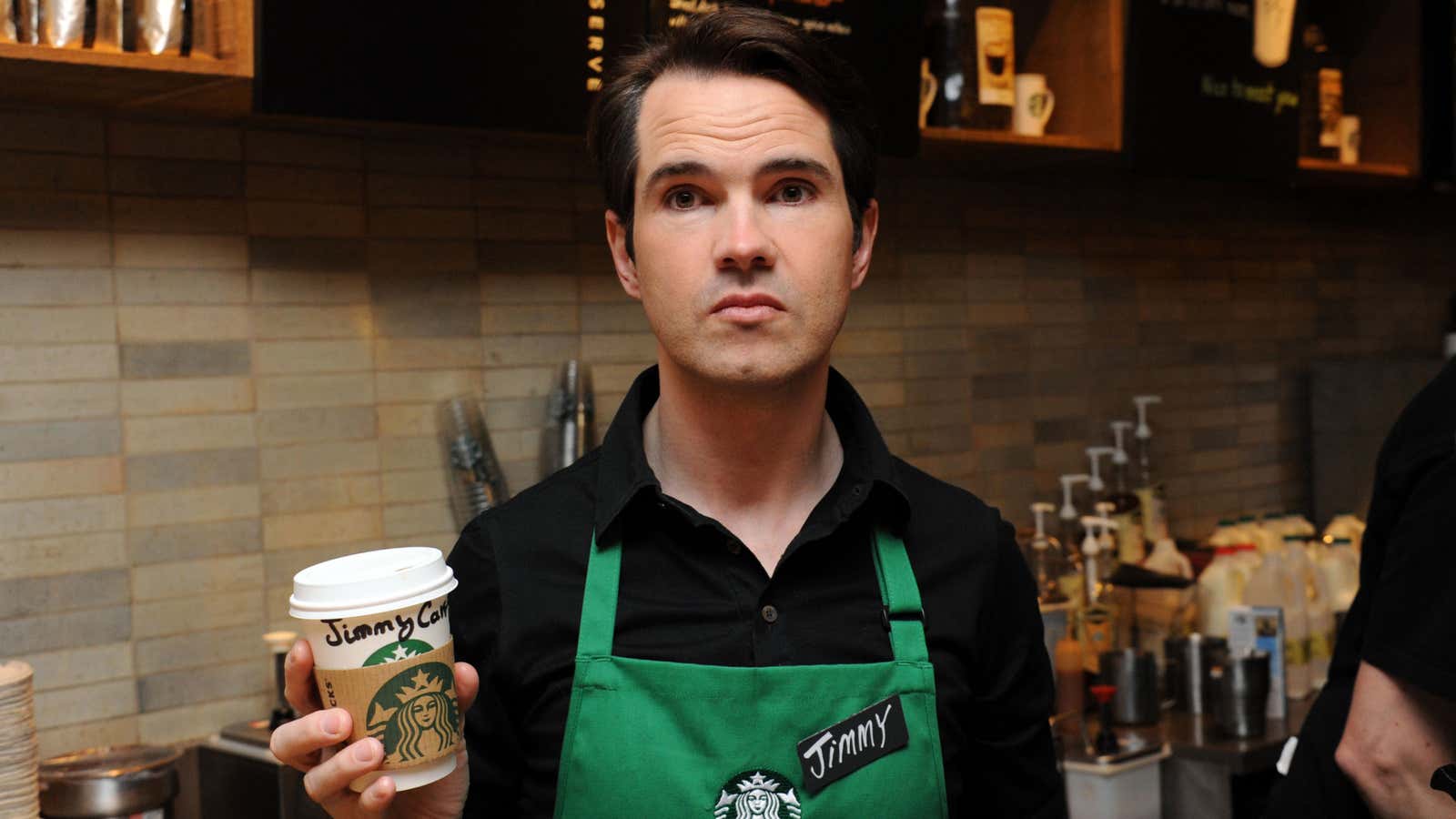

There are of course a ton of extremely successful, healthy people who drink inordinate amounts of coffee. Voltaire was rumored to have drunk 40 to 50 cups per day. Meanwhile the FDA has set a pretty arbitrary limit of 400 milligrams of caffeine per day as healthy, which is like one Starbucks venti or two 5-Hour Energies. A huge number of people are drinking a lot more than that. When it’s in our oatmeal, though, that’s a call to action.

The FDA has not set a level for children, but “the American Academy of Pediatrics discourages the consumption of caffeine and other stimulants by children and adolescents.”

It feels right that the FDA is uneasy about marketing stimulants to children, at least in the context of an organization that is convinced about regulating marijuana and alcohol as it does. It also seems weird to address it now and not years ago. Sometimes, in the vein of guns, lead, and soda, it takes tangible health concerns and a crescendo of moral outcry before we seriously evaluate the prudence of products long on the market. At that point, their use culturally ingrained, reactions can be exaggerated and emotional. (“You can take away my Rockstar Energy Drink when you pry it from my cold dead hands.”) So while the outcome of all this is not likely to be as extremely reactionary as setting an alcohol-like drinking age for coffee, that’s not an altogether impossible outcome depending on where they draw the line in the grounds. As Taylor put it, “If necessary, and if the science indicates that it is warranted, we are prepared to go through the regulatory process to establish clear boundaries and conditions on caffeine use.”

James Hamblin, MD, is The Atlantic’s Health editor.

This originally appeared on The Atlantic. Also on our sister site:

The biggest mistake conservatives make about Keynes

Latvia is the new hope for zombie economics

The strange Thai insurgents who like sorcery and get high on cough syrup