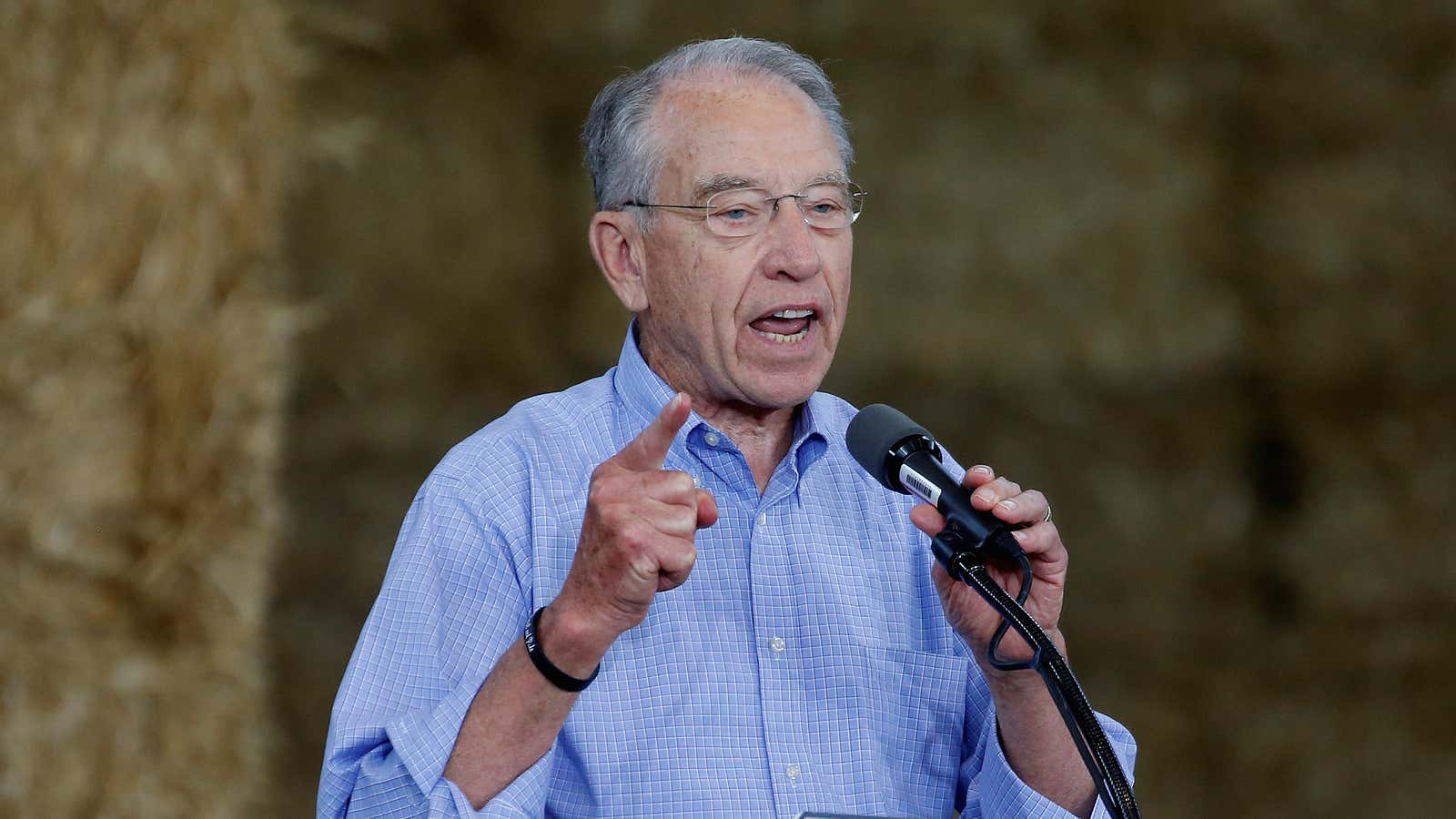

The most important US national election on November 8 is for the presidency. But the second most important contest, at least symbolically, is Republican senator Charles Grassley’s reelection bid in Iowa.

Every Senate contest is important, of course. Democrats have a solid chance of winning back the chamber, but it’s by no means a done deal. Currently, 538’s projections give Republicans a 25% to 30% chance of retaining control. Among other things, the balance of power in the Senate will determine whether a president Hillary Clinton (if there is a president Clinton) will be able to appoint a liberal justice to replace former Justice Antonin Scalia, a staunch conservative—or whether she’ll get to appoint any justice at all.

This is why Grassley is so vital. Grassley is the head of the Senate Judiciary committee. He’s been a key figure in the Senate’s refusal to hold hearings on Merrick Garland, the judge nominated by president Barack Obama to replace Scalia, who died in February.

The Senate’s decision to wait eight months to hold Supreme Court nomination hearings is unprecedented. But at the same time, it feels inevitable. Over the past twenty years, Republicans have become more and more committed to the kinds of tactics political scientist Jonathan Bernstein refers to as rejectionism. Rather than working for compromises, Republicans have increasingly defaulted to simply trying to block everything they can. If Grassley were to lose his Senate seat, it would send a clear message to Republicans to reconsider this strategy. Unfortunately, he looks likely to win—which means the American public can expect more stonewalling in years to come.

The decision to stonewall Garland—a moderate candidate whose age means he will have a relatively short tenure on the court—is a perfect example of this strategy. Republicans could do much worse, and may do much worse if Clinton and a Democratic Senate are able to put a young fire-breathing leftist on the court. But the GOP leadership has decided its better to risk total defeat later than to compromise now.

Part of the reason for this is that Republicans currently are terrified of their own voters. Since the rise of the Tea Party in 2010, a number of sitting Republicans have lost primaries to more radical candidates. This happened most recently to House Majority leader Eric Cantor, who lost his seat in a stunning upset in 2014.

It’s very rare for an incumbent like Cantor to lose a primary. No Senators did this year, and the only GOP House primary loss not involving redistricting (paywall) was Tim Huelskamp, a Tea Party radical in Kansas targeted by business interests. (A Democratic representative, Chaka Fattah of Pennsylvania, lost his primary after being indicted on corruption charges.)

But federal legislators aren’t necessarily rational actors; they’re always scared of losing their seats. And a dramatic surprise loss like Cantor’s—or a dramatic surprise win like Donald Trump’s—instills a sense of urgency in a way that Huelskamp’s loss has not.

But if Grassley lost, now that would be another matter. Based on the strength of public disapproval over the Garland debacle, Democrats were able to recruit former lieutenant governor Patty Judge to run against him.

If Judge were to win, that would send tremors through the GOP. It would be an iconic story about how obstructionism has electoral consequences. It would give Republicans a reason to worry about not compromising. They would still be working towards conservative policy goals, of course. They’d even be working towards those goals more effectively, in many cases. But they’d also have an incentive to fight for their priorities through good faith negotiation, rather than through a blanket refusal to govern.

Alas, Judge’s initial promise has not panned out. Grassley is a popular politician who has served as Iowa’s Senator since 1981. He thumped his Democratic opponent in 2010, winning almost 65% of the vote.

While popular with Democrats, Judge is still down by double digits, according to the Huffington Post poll average.

Meanwhile, without the fear of consequences, Republicans have begun to double down on their obstructionism. On Oct. 17, Senator John McCain in Arizona promised that if Republicans retain control of the Senate, “we will be united against any Supreme Court nominee that Hillary Clinton, if she were president, would put up.”

McCain’s comments were widely criticized, and he has since half-heartedly walked them back. As Laurel Harbridge Yong, a political science professor at Northwestern, notes, it’s unlikely McCain or a Republican Congress would actually follow through on such threats, even if the wanted to. “It would definitely be unprecedented if they continue to block any nominee and didn’t even bring them forward for a vote,” she said. “Realistically I just don’t think they could hold up an appointment of new justices.”

The fact that McCain, a former compromiser who is himself embroiled in a tough reelection campaign, has voiced support for knee jerk obstructionism underlines the problem, though. Grassley and McCain don’t look like they’re going to suffer for their unprecedented embrace of obstructionism. Meanwhile, Mark Kirk, a Republican Senator from blue Illinois who criticized the Garland policy, looks poised to go down to defeat.

Until they are given a striking reason to change their minds, Republicans are likely to continue viewing obstruction as the safest path. This means that unless Grassley, or McCain, or someone else gets unexpectedly defeated at the polls, the Supreme Court nomination fight, and governing in general, is just going to get uglier, no matter who becomes president on November 8.