American immigration reform won’t cost taxpayers an arm and a leg as some opponents say. But maybe the real worry is that it will be bad for the 12% of Americans without a high-school degree. Giving unauthorized workers legal status and giving more low-skilled foreign workers temporary visas could force down wages and take away jobs for low-skilled Americans. Right?

It might be easier if we talk about manicures.

The manicure business in the US has been driven by immigrants. It’s low-skilled, low-capital service work. For instance, Vietnamese immigrants and their families make up nearly 80% of manicurists in California, and 40% of manicurists across the nation.

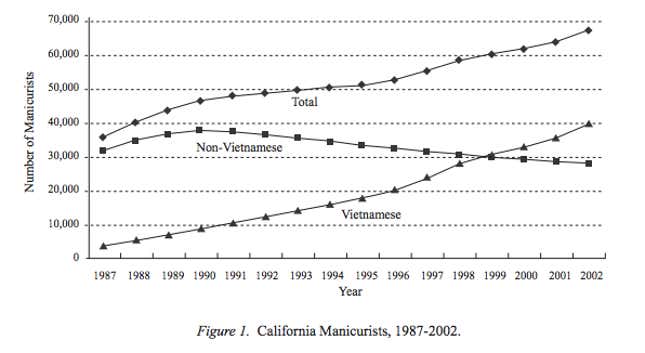

So you could say that foreign manicurists have taken the jobs of hard-working American hand-and-foot maintainers, but the reality is more complicated. A study in California (pdf) found that between 1987 and 2002, 35,700 Vietnamese manicurists went to work there. But they didn’t exactly put native-born workers out of business. For every five Vietnamese who entered, two non-Vietnamese workers were displaced—but the authors are quick to note that most of that effect came from workers choosing not to enter the profession, rather than people who already worked as manicurists losing their jobs.

Why was this possible? Because the immigrants were—wait for it—innovators in the manicure space. They developed the idea of the standalone nail salon that reduced costs, “making a once-exclusive service commonplace.” That meant more nails to paint, not just more workers per nail. The benefits of immigration accrued to people who got their nails painted, to the new immigrants, and even to the remaining non-Vietnamese manicurists.

While nail-care business might not be the perfect stand-in for all low-income work, it does reflect what economists find more broadly: When new immigrants come, it does mean new competition for similarly-skilled local workers, but the new immigrants may also create opportunities that lead to more investment, which maintains wage growth and leads to economic growth. Indeed, with more immigration, average wages seem to rise, not fall.

But the American workers most similar to low-skilled immigrants are uneducated Americans. Economists looked at how immigration affected them between 1990 and 2006, when a lot of unauthorized workers were coming into the country. If they assumed every new immigrant had the exact same abilities as a native worker (which obviously isn’t true, starting on the language front), the effect of immigration on the wages of native workers who didn’t finish high school fell 0.6% over 16 years, while those of everyone else improved. In a more accurate simulation, they found that less-educated natives saw their wages increase by 0.3% due to immigration, and average wages increased 0.5%. That’s not so bad at all.

And, of course, immigrants coming to the United States see huge increases in their wages and productivity, but most Americans aren’t taking that into account when considering the bill.

Which makes this a good opportunity for a correction: Actually, the most similar worker to a low-skilled immigrant is another recent low-skilled immigrant. This group faces the largest downward pressure on wages from increased immigration. That could mean that low-skilled services performed by recent immigrants, from nail care to landscaping or child care, will remain cheap if the immigration bill passes. That depends, too, on how many currently undocumented immigrants move up the path to citizenship and better jobs.

But high school dropouts face bigger problems than new immigrants—they lack basic education when those skills have never been more important—which probably should have been obvious from the beginning.