As Americans head to the polls today to elect the person in charge of the world’s largest and most powerful economy, the rest of the world is watching more closely than perhaps ever before.

That’s because outside the US, the rise of Republican candidate Donald Trump is rarely viewed in terms of income inequality or changing demographics, as it is at home, but as a movement that runs counter to the very idea of America. While Hillary Clinton’s long history in public office—and questions about everything from her cyber-security practices to her husband’s financial connections—are issues overseas, too, it is the Trump campaign that seems to be the most unsettling.

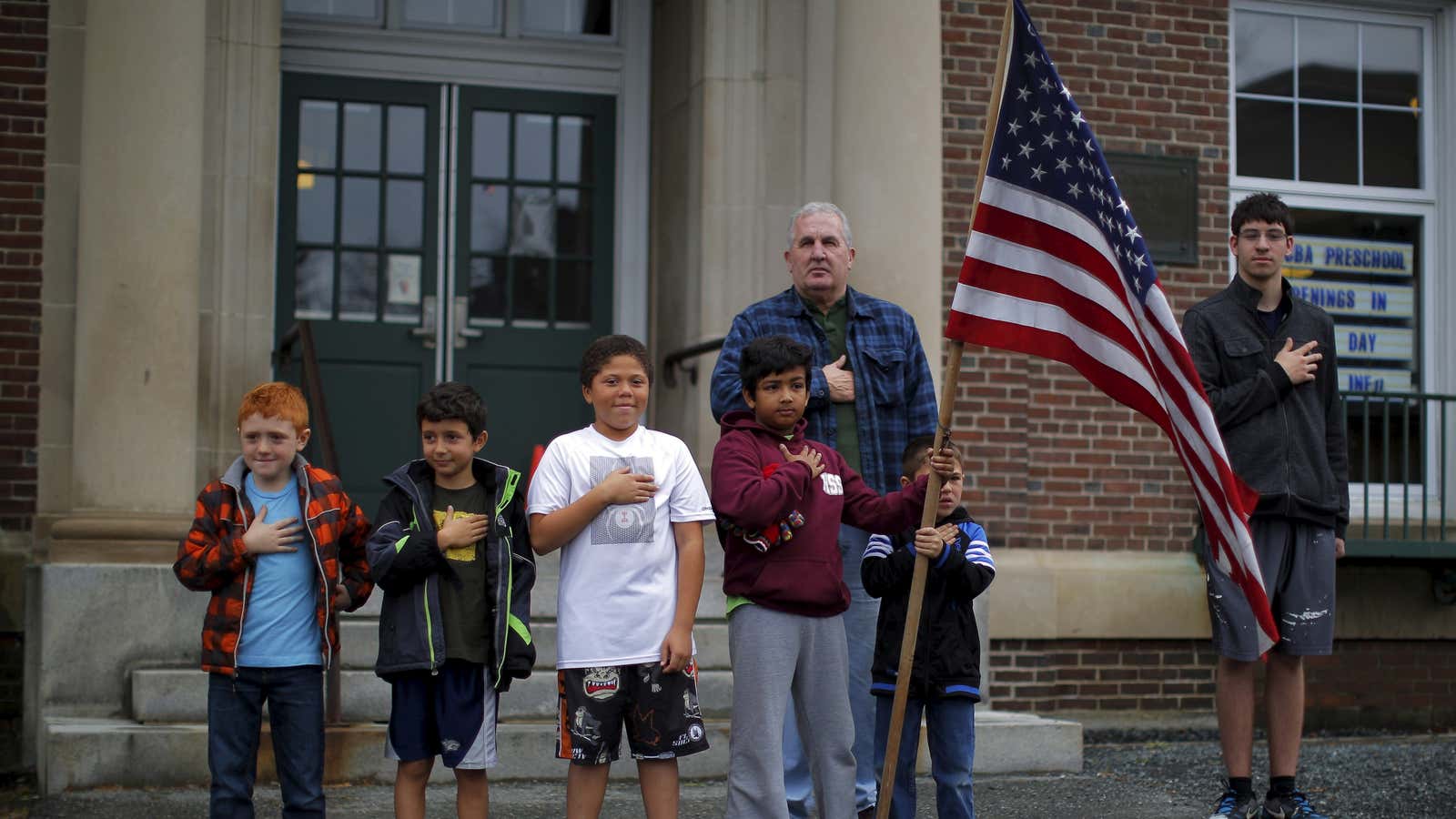

Watching a country whose history and economic strength is rooted in embracing waves of immigrants, and based on founding documents that declare all men “created equal,” turn to racism, sexism, and xenophobia has profoundly shaken how non-Americans view the US. Being an American overseas during the past year has meant facing a barrage of questions from friends and strangers that all boil down to, “What the hell is going on? I thought your country was better than that.”

No matter who the victor is, the ugly campaign will have a lasting global impact.

The election has “diminished that idealistic view of America,” says Gucharan Das, an author and historian based in New Delhi. “You realize that Americans are like everyone else… this kind of nationalism and jingoism, it is universal,” he added. “Join the club. American exceptionalism is over.”

While the US’s foreign policy mistakes and swashbuckling overreach are rarely overlooked outside the country’s borders, the darker forces at work in this election have made non-Americans question the US’s stated global goals. How serious is the US about fighting corruption, or pushing for fair trade, democracy, and global human rights, anyway?

This presidential campaign has caused the “moral standard” set by the United States abroad to erode, said Steven Goh, an Australian tech entrepreneur based in Hong Kong. “There are other countries, like Russia and China, who have their own successes, but appear in the public domain to rationalize their shortcomings by picking US examples of failure. Trump is providing them with an awful lot of fodder,” he said.

The campaign has been especially alarming for residents of countries where journalists and political opponents are regularly jailed, minorities systemically suppressed, and dictators reign with impunity.

“My colleagues from China say ‘please, please tell me Trump isn’t going to win,’” said Christopher Balding, an American living in Shenzhen, where he teaches economics at the University of Peking. These are people from mainland China who have lived in the US before, are positive toward the country, but harbor “valid and understandable concerns” about this race.

The world looks to the US for “world leadership,” Balding said, “for how a country is run respectfully between political enemies, and it is just not there.” The tone of the televised debates and other campaign events has made it hard not to think, “oh my god, this is nothing more than a high school food fight,” he added.

Zhang Zongliang, a 25-year-old from Guangzhou, is heading to Boston’s Northeastern University to study computer science next year, but he might rethink those plans, depending on the election results. “If Trump becomes the president, I am worried that US will fall apart, then what’s the point of going to the US? I would rather return to China,” he said.

This year’s presidential race is the most “emotional” and “irrational” of any recent US elections, said Lian Qingchuan, a Chinese political commentator and former reporter, who was a Columbia University fellow in the US for several years. What strikes him the most, though, is how the mentality of US society has seemed to change, with Trump successfully using nationalism, xenophobia, and social inequality to stir up emotions.

Now there’s little non-Americans say they can do but pray, and try to appeal to Americans to vote against Trump.

The Irish Times summed up the feelings of many non-Americans in a recent editorial titled “Why we hope Hillary Clinton wins”:

The choice is between continuity and wild unpredictability, internationalism and xenophobia, economic rationality and voodoo economics, a commitment to the rule of law or a contempt for everything except self-interest. But we don’t get to vote—all we can do is hope, for our sake and theirs, that Clinton wins this election. America, listen to the better angels of your nature!

Zheping Huang, Echo Huang Yinyin, and Josh Horwitz contributed reporting.