The bank’s future may be very different—but more profitable

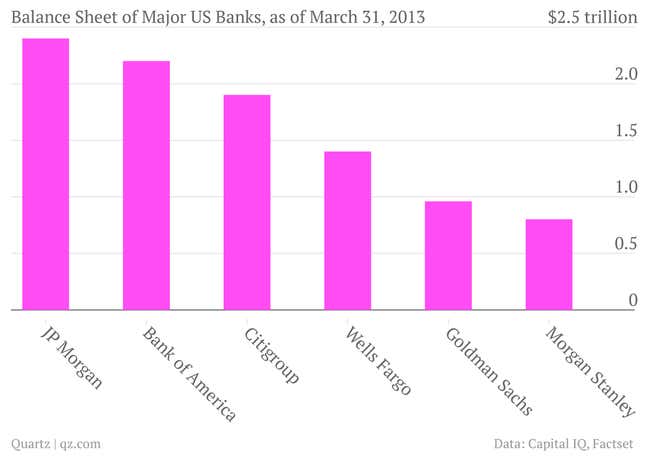

In the hyper-competitive world of finance, Wall Street banks have certain characteristics for which they are known. JP Morgan has the biggest balance sheet. Bank of America and Citigroup are major retail banks. Goldman Sachs is, well, Goldman Sachs.

What does Morgan Stanley stand for? It has long been known as an investment banking powerhouse, often going head to head with Goldman Sachs in several areas such as mergers and acquisitions (M&A) and initial public offerings (IPOs.) But Morgan Stanley’s investment banking operations have faded a bit from the spotlight and its trading arm had been disappointing though is staging a comeback, while its wealth management arm is getting more attention—and seeing more success. Overall, Morgan Stanley hasn’t completely adjusted to the world after the financial crisis. In Wall Street’s map of the world, the bank is in something of a no-man’s land.

Morgan Stanley’s transformation reflects the broader changes facing the finance industry, which is dealing with a new normal that includes increasing regulation, rising costs in what are deemed risky business areas and falling compensation. Bankers and traders who used to consider themselves masters of the universe are having to come to terms with a more mundane, but steadier workplace, instead of the high-flying days of huge profits coming on the back of risky bets.

Although it’s growing stronger, Morgan Stanley is still seen as one of the weaker Wall Street firms that survived the financial crisis, and it’s the smallest of the big banks. In his annual letter to shareholders in March, Morgan Stanley CEO James Gorman indicated that it was revisiting three existential questions: “What do we do? How do we do it? With what result?” The bank, in short, faces something of an identity crisis.

A new Morgan Stanley, years in the making

Properly speaking, “investment banking” refers only to advisory services (helping companies with M&A) and underwriting (arranging for them to issue shares.) A modern investment bank, however, has a much broader portfolio, which also includes lending money to corporations and trading various financial products such as stocks, derivatives, bonds and currencies. The relative size of each of these divisions varies from bank to bank.

Morgan Stanley was formed in 1935 as the investment banking half of JP Morgan, after the newly passed Glass-Steagall Act forbade banks from engaging in both commercial banking and investment banking. Morgan Stanley immediately became a player in underwriting, gaining an almost 25% market share in IPOs within its first year of business. In the 1970s, it established divisions for equity sales and trading, an M&A group, and asset management.

In 1997, the bank merged with Dean Witter, which sold stocks and bonds to retail investors. The deal was an attempt to create the world’s biggest brokerage, combining Morgan Stanley’s worldwide menu of investment options with Dean Witter’s millions of customers. But Morgan Stanley’s highbrow ways didn’t mesh with the hometown feel of Dean Witter, whose brokers took a more suburban, laid-back approach. A 1997 New York Times analysis likened the deal to a merger between the populist superstore Sears and the snooty fashion emporium of Saks Fifth Avenue.

Meanwhile, investment banking remained at Morgan Stanley’s heart. Despite losses and scandals after the burst of the dot-com bubble, the bank saw successes in the 2000s. In 2004, it boasted that it held the top spot in global equity trading, equity underwriting, and IPOs. It was number two in global debt underwriting and global M&A.

It was risky moves in the non-brokerage part of the business that almost brought Morgan Stanley to its knees.

Under John Mack, who became CEO of the bank in 2005, it took increasing risks. In December 2007, Morgan Stanley had to write down $9.4 billion it had lost betting on iffy subprime mortgages—the first quarterly loss in its 72-year history. The bank got a $5 billion capital infusion from China Investment Corp that year. But the credit crisis roiled Wall Street and a year later, it needed another $9 billion cash injection from Japan’s Mitsubishi UFJ, which saved it from collapse.

Doubts about Morgan Stanley’s stability remained, partly because of how much debt it held from troubled European countries. In 2011, ratings agency Standard & Poor’s downgraded Morgan Stanley, and its market capitalization fell to $25 billion, from about $47 billion a few months earlier. At that size, Wall Street watercooler talk in November 2011 turned to whether Morgan Stanley could be a takeover target for Wells Fargo or another bank. By the summer of 2012, investors feared that Moody’s would slash the bank’s rating by a full three notches, taking it to the second-lowest investment-grade ranking of Baa2. (In the end, the cut was only by two notches.)

There is still speculation that within the next five years, it could be absorbed by another firm—whether it’s minority stakeholder Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group or another financial institution. Morgan Stanley has recovered to some extent; its market cap is now back to around $47 billion.

A shift in focus

Since the financial crisis, Morgan Stanley and other banks have not only had to recover from the turmoil but grapple with tougher regulations (designed to prevent another crisis), declining revenue, and pressure from shareholders for higher returns. It’s been up to Gorman, who took over as Morgan Stanley’s CEO in 2010 in the aftermath of Wall Street’s meltdown, to overhaul the bank for the new, more austere environment.

In its present form, the bank consists of three business areas: wealth management (encompassing financial advisory services and investment products), institutional securities (investment banking operations, equities, fixed income, commodities, and currencies), and asset management (investment funds mainly for institutional investors). For Gorman, a key part of the answer to the questions he posed in his March letter to shareholders has been to shift the focus away from Morgan Stanley’s investment banking roots, and towards its wealth-management business.

That’s not surprising given Gorman’s background. He is neither an investment banker nor a trader but instead came from the bank’s retail brokerage unit, which he helped turn around. A former McKinsey & Co. consultant, he also led the the January 2009 deal to acquire a 51% stake in Citigroup’s Smith Barney brokerage business, combining it with Morgan Stanley’s own wealth-management unit.

Last July, the bank announced it was going to take full control of Smith Barney. It closed that deal last month, marking a major milestone for Gorman in his four-year effort to acquire the entire business. The bank’s first national ad campaign in four years launched recently, focusing on wealth management.

Gorman’s background is not the only reason for the new emphasis. Post-crisis, some banks have turned to wealth management as a more dependable, less volatile business. ”The benefits to Morgan Stanley of owning a wealth management business of scale are unmistakable: sizable and stable revenues, a substantial deposit base, low relative capital usage and a growing demand for professional advice,” Gorman said in his March letter to shareholders.

More than 40% of the bank’s revenue now comes from wealth management, as compared to 25% in 2008. At the same time, investment banking revenue has been going down over the last five years, and trading revenue has been volatile (it dropped 42% in the first quarter).

Sources close to Morgan Stanley argue that investment banking has not taken a back seat and the strategy is to have both a premier institutional securities business along with the largest wealth management division in the world, which complement each other.

When Morgan Stanley releases its quarterly earnings tomorrow, analysts will be watching its trading figures, particularly since both JP Morgan and Goldman Sachs reported strong trading revenue in what analysts had expected would be a difficult quarter. They’ll also be watching to make sure that Morgan Stanley’s wealth management is continuing on a profitable path.

By owning 100% of its wealth management business, Morgan Stanley can now use the largest retail distribution sales force in the world to market IPOs, municipal bonds, secondary offerings and other products from its institutional securities business to individual investors. Morgan Stanley will also get an additional $56 billion in deposits from owning all of the brokerage business, which the bank can use to expand its lending on the institutional securities side.

Unhappy bankers

The perception that Gorman has downgraded investment banking in his priorities has irked some of his employees, many of whom were already upset over cuts in pay. At a time of general austerity in the industry, Gorman tightened belts more than most. Last year, the bank capped cash bonuses at $125,000 and this year deferred 100% of bonuses for some senior bankers and traders, which means they will get a bulk of their compensation in the future. Employees in wealth management didn’t face similar bonus deferral. Gorman made clear he had no tolerance for complaints, saying if bankers were really unhappy, they could leave.

Some have taken his advice. A particularly significant defector was Paul Taubman, the co-head of investment banking, who decided to leave after Gorman in November made the other co-head, Colm Kelleher, the sole head of the division. Taubman was a prominent rainmaker, known to have great client relationships that helped Morgan Stanley win deal assignments. Choosing Kelleher, who came from a trading background, over Taubman signaled to staffers in the investment banking division that they were no longer the favorite children.

Another signal was the departure of Kate Richdale, head of Morgan Stanley’s Asia-Pacific investment banking business. In the past, sources said, the bank would have fought to keep her, but with investment banking becoming less of a priority she was let go to arch-rival Goldman Sachs.

Since then, Ji Yeun Lee, the deputy head of investment banking, has left, too. The firm has also lost a host of M&A bankers, many of whom went to smaller boutiques; one was hired by Twitter. Even its industry-leading technology practice, which includes M&A and IPOs, has seen some losses, which were unheard-of in the past. One banker who recently left the firm said he felt like investment banking had become a “second tier” business within Morgan Stanley.

A source close to Morgan Stanley said that investment banking is a treasured and supported part of the firm, and its performance since Gorman became CEO reflects that. Morgan Stanley still competes head to head with Goldman Sachs and others when it comes to M&A deals and IPOs. For the first half of 2013, Dealogic data showed Morgan Stanley ranked third in global M&A and number four in the US. It’s in second place for global IPOs and for global equities.

But numbers aren’t everything. “None of the banks are in the same shape as before the crisis, but Morgan Stanley seems like it’s changed the most and it’s still going through the shift,” said one senior banker who has thought about leaving. “Depending on what it looks like in the end, I don’t know if I’ll recognize it or want to stick around for it.”

Cautious optimism

Less controversial are Gorman’s moves to eliminate risky assets and trading, measures that have also been taken by other banks in the aftermath of the financial crisis. And like other banks, Morgan Stanley is also slashing jobs, cutting around 1,600 positions.

Investors have every right to be nervous. The company’s share price has fallen almost 20% since Gorman took the helm, and progress on the restructuring has been slow. In 2010, Gorman characterized 2009 as a year of transition, 2010 as a year of execution, and 2011 as the year it would all bear fruit. Then he pushed that estimate back to 2012. In 2013, the process still seems to be continuing.

However, there are signs that Gorman is gaining traction. The bank’s shares are up almost 40% this year. In the last five years, the bank’s stock has underperformed compared to the S&P 500, Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan, while it has done better than Bank of America and Citigroup.

Analysts note some promising signs. “The biggest day in Morgan Stanley’s corporate lifecycle was July 8, 2012, because that’s the day when Morgan Stanley finally completed the largest brokerage merger in history,” Mike Mayo, an analyst at Credit Agricole, told Quartz, referring to the day the bank inked the deal with Citigroup. He recently named Morgan Stanley as his top bank stock pick. “I think the brokerage business at Morgan Stanley is one of the undiscovered stories in the financial services world.”

Its equities trading team is also back near the top. “The gap to #1 has never been closer,” Credit Suisse analysts led by Howard Chen wrote in a note on May 16. ”We believe Morgan Stanley has done a very admirable job of closing key revenue gaps in the equities business over the last few years.”

A key measure for investors is Morgan Stanley’s return on equity (ROE). That bank has forecast a 10% ROE by 2014. It will take some work to get there. ROE in the first quarter of this year dropped to 7.5%, from 9.2% a year ago. By contrast, Goldman Sachs had an ROE in the first quarter of 12.4%; JP Morgan’s was 13%.

The weak link is in its fixed income, currencies, and commodities business, or FICC. If Morgan Stanley were to sell off any of its business, FICC would be the one, analysts speculate. “Half the company is brokerage and asset management, and that half is revved up and ready to go,” says Mayo. “[FICC is] really the weakest part of the company.” The FICC group fell well short of analyst expectations in the first quarter of this year, and, Nomura analyst Glenn Schorr pointed out in a research note, its revenues are also volatile.

All the same, the bank is generating returns in its other businesses, many of which depend less on fickle markets. Optimists also hope the firm can do more in Asia. There, points out Credit Suisse’s Chen, its partnership with Mistubishi UFJ gives it an edge, in the form of access to Japanese borrowers and Mitsubishi’s more than $1 trillion of deposits.

Morgan Stanley is still a force to be reckoned with in investment banking—but if it will henceforth be known more for its prowess in wealth management, that may not be a bad thing. After the drama the bank has been through, the dependability of boring, steady growth could be just what Morgan Stanley needs. ”Gorman is taking the not-so-great situation given to him and making it better,” one senior banker said. “A lot of people here recognize that and are behind the effort.”