Come December, the storefronts of Paris fill up with a familiar-looking log. Thick and brown, with a sugary sheen, the bûche de Noël, or Yule log cake, is a holiday spectacle in France. Patisseries roll out their chocolate sponge cakes with a thick layer of cream in classic and inventive forms, an act of cultural pride.

But elsewhere in the world, the famed French cake has its own legacy. The journey of the bûche de Noël in Vietnam and its subsequent diaspora is a story of geopolitics, socioeconomics, and cultural preservation.

It should come as no surprise that the French, who ruled Vietnam for 67 years, left behind a trail of breadcrumbs when it was forced out of the country in 1954. Vietnamese cuisine had previously been influenced by the Chinese in the north and to an extent by Indian flavors by way of Khmer and Cham traditions. But in the late 19th century when the French arrived in southeast Asia, Vietnam’s rice, noodle, chili, fish sauce, and herb-forward dishes were joined by foods using butter, bread, milk, and sugar.

As early as 1910, a newspaper based out of then-Saigon called Lục Tỉnh Tân Văn advertised for Pâtisserie Roussenq and its “’delicacies made in the Parisian manner,’ including cakes made with sweet fruit liqueurs,” says culinary historian and independent scholar Erica J. Peters. By then, coffee and baguettes could be found in Vietnamese cities for breakfast. According to Peters, the amount of chocolate imported into French Indochina increased by 189% over a decade, from 75 tons to 142 tons in 1923.

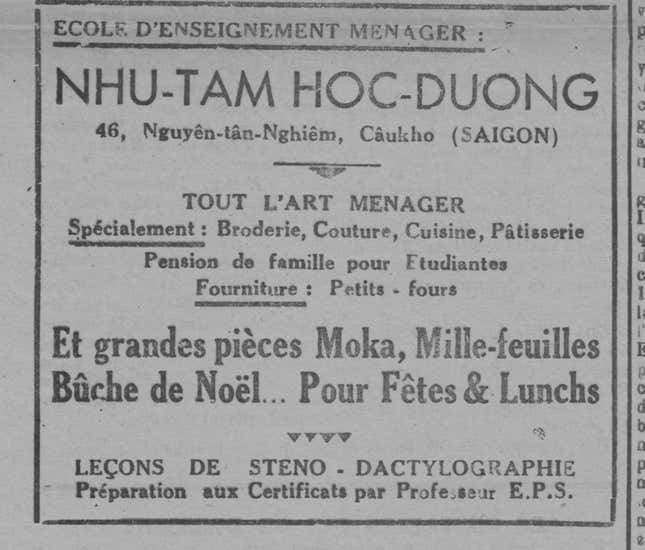

Then in August, 1941 the French paper L’Écho annamite ran an ad selling lessons in Saigon in baking, cooking, embroidery, and sewing. The lessons included classes on making petits-fours, chocolate cake, mille-feuilles, and bûche de Noël.

“The Vietnamese have an affection for the bûche de Noël,” says Andrea Nguyen, author of five cookbooks, including one about phở coming out next February. Nguyen left with her family in 1975 like so many other refugees fleeing the imminent fall of South Vietnam. They landed in San Clemente, California, where her mother set up a tailoring business. To celebrate with their new American friends at Christmas time, the Nguyen family baked 25 mini- and full-sized bûche de Noël cakes to distribute.

Her father writes that they shared bûche de Noël with friends because they “wanted to express that the Vietnamese people coming to the USA are having something ‘sophisticate’ with them.”

By the time Nguyen’s family left the country, the cake was a specialty item in Vietnam (certainly not for everyday consumption). Butter, refined sugar, and white wheat flour were (and are) expensive in the country—not to mention the prohibitive cost of an oven—so people weren’t making cakes at home. People—those with money—were ordering them. Says Nguyen, “If you have means, if you’re sophisticated, urbane, you’d know about it.”

Today, Vietnam is less than 10% Christian, but Christmas festivities are serious (video in Vietnamese), especially in Ho Chi Minh City. The holiday is for socializing, going out in the street, and taking kids out to play, not a night for staying home with family, like in the US. Giving out the bûche de Noël is a key slice of the fun. It mimics the Yule log burned in homes to symbolize a new year and harvest, and is traditionally eaten at the culmination of the Christmas Eve meal, called the Réveillon.

Each year in Vietnam, bakeries trot out their sugary versions of the beloved French cake. Kinh Đô Bakery, a chain in three Vietnamese cities, reported in 2010 (link in Vietnamese) that they made 140,000 cakes in 50 different varieties, including a slew of different flavored logs. Of all their cakes, Sweet Home Bakery in Ho Chi Minh City tells Tuổi Trẻ newspaper, the yule cake is still the favorite (link in Vietnamese). In 2007, the bakery’s celebrations included gifting a 22-meter-long version (video in Vietnamese) of the log, and the following year they served 50,000 people with their 4-ton cake (link in Vietnamese).

The cake goes by “bánh khúc cây giáng sinh” (Christmas stick cake), “bánh bông lan cuốn” (rolled sponge cake), or simply “bûche de Noël.”

Just as in Paris, where some bakers have abandoned the traditional scored frosting and meringue mushroom caps for more avant-garde shapes and flavors, Vietnamese bakers have given their own twist on the log by adding flavors like matcha, mango, and coconut and cranking up the kitsch and cuteness.

Image by Steve Rainwater on Flickr, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.