For around a year now, the Chinese government has been trying to curb “shadow banking,” as lending to local government investment proxies and other insolvent vehicles through difficult-to-trace channels is known. Shadow banking is now thought to be as big as 36 trillion yuan ($5.8 trillion), according to JP Morgan.

There’s been more shaking this last week. The government rolled out two new policies directed in most part at limiting the creation of wealth management products (WMPs), which securitize a good deal of shadow banking financing, selling the products on to retail investors. As of the end of March, WMPs had securitized debt worth of 8.2 trillion yuan.

Will this have more effect than the measures taken so far? Not necessarily, says Patrick Chovanec, chief strategist at Silvercrest Asset Management and expert on China’s economy.

“[The government has been saying] ‘We need to crack down on risks in interbank and shadow lending.’ Obviously there’s a growing awareness of risks,” he tells Quartz. “But if you look at what has happened since [the new administration effectively took over] in October, there’s been a renewed credit boom to try to prop up investment. That’s what policy has been in practical terms with almost no control over expansion of shadow credit.”

Take for instance the aggressive, multi-pronged crackdown in March that sent financial markets into a tailspin. Société Générale’s Wei Yao called them “the harshest and most concrete tightening measures” on WMPs that China had yet seen.

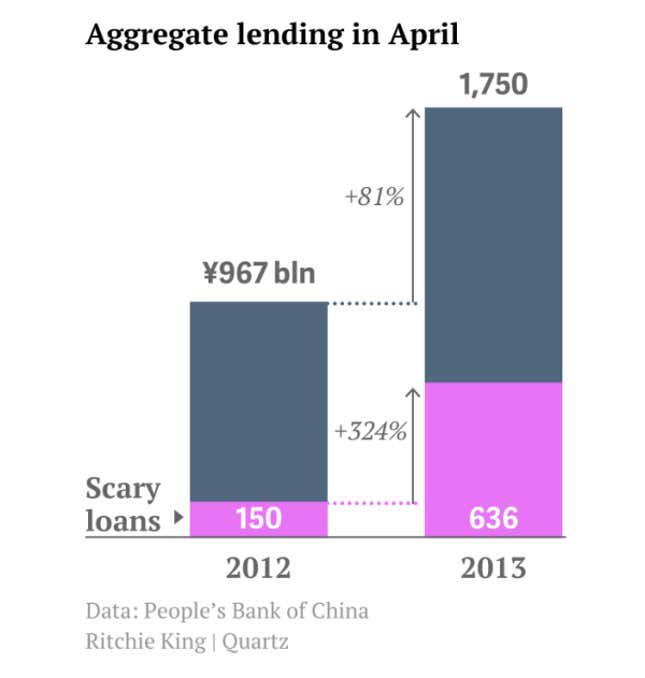

April’s lending data should give a sense of how effective those were. In April alone, the composite growth of loans associated with shadow banking (link in Chinese)—namely, entrusted loans, trust loans, bank acceptances and financing to non-financial enterprises—increased 324% (see above chart).

Why has the government’s effort to stamp out shadow banking been so ineffective?

Probably because, after years of aggressive lending to boost growth, the Chinese economy is now perilously dependent on new credit for growth—half of Q1 GDP came from investment. That puts the government in a tough spot. Either it clamps down on lending and watches growth sputter, or it lets credit keep flowing—and bad debt keep piling up—in order to spur economic growth.

Lending data for April suggest that, despite government efforts, it’s choosing the latter.