It’s been a tough few days. But while we were distracted by Trumpocalypse 2016, Marvel’s latest cinematic opus, Dr. Strange, crossed the $150 million mark at the domestic box office—and is fast approaching half a billion in revenues internationally. Whatever its final total, Dr. Strange is clearly going to be another one of the Marvel Cinematic Universe’s biggest hits, possibly the biggest that doesn’t feature Robert Downey Jr. as Iron Man or Chris Evans as Captain America.

But for those advocating inclusion, diversity, and authentic representation, whether in politics or pop culture, Dr. Strange’s success is less welcome. While it has received generally favorable reviews, the Benedict Cumberbatch film highlights Marvel’s resolve in refusing to showcase Asian characters in its iconic narratives. At a time when Asian American stars are lighting up television screens, why is Hollywood lagging so far behind?

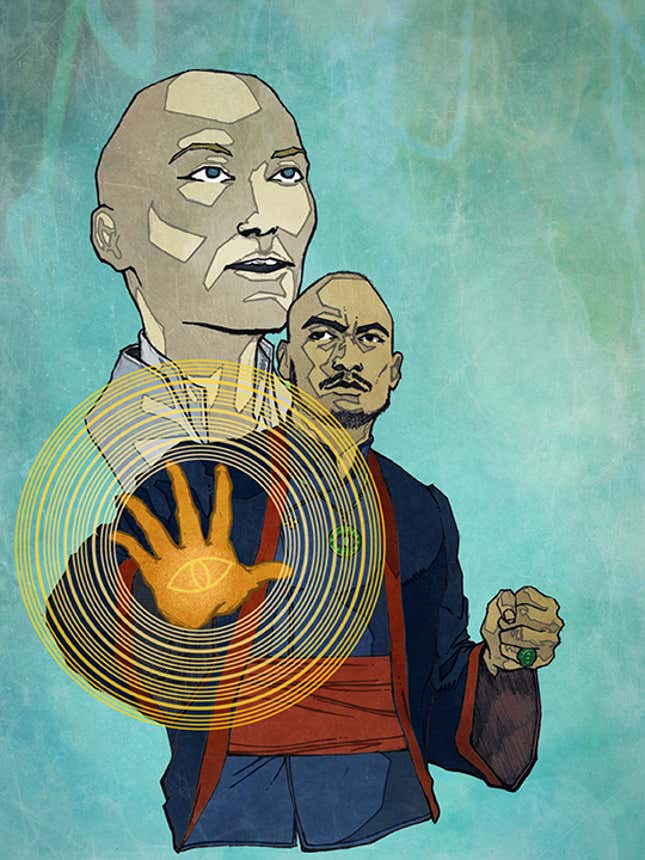

Importantly, the studio has shown little hesitation in altering established canon to create opportunities for talented actors of other backgrounds. The most obvious example was Marvel’s decision to transform comic hero Nick Fury, a cigar-chomping white New Yorker, into the bald and beautiful character played by Samuel L. Jackson. Despite initial controversy, Jackson’s portrayal was so perfect that the comics themselves have since adopted him as their new, true-blue Fury.

But there’s never seemed to be room for Asians in the Marvel Cinematic Universe. There have been sidekicks and cameos—the god Hogun in Thor, played by Tadanobu Asano; Dr. Helen Cho in Avengers: Age of Ultron, played in a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it cameo by South Korean actress Claudia Kim—but no roles of consequence. (A good test for the importance of a character to a film: Consider whether an “airplane edit” of the movie, shortened to fit a 90-minute flight, would still contain that character.)

Even the opportunity to cast Asians as canonically Asian villains, like Iron Man 3’s Mandarin, have been deleted with a few writerly keystrokes.

With Dr. Strange, Marvel Studios had a chance to rectify this pattern of erasure. After all, the story of Stephen Strange has the dashing and arrogant neurosurgeon losing the use of his hands, and flying to Asia—to Asia!—on a desperate recovery quest after science fails him. The master he meets in this magical quest, the Ancient One, is revered as the Sorcerer Supreme, the greatest mystic in the known cosmos, and he ultimately takes Strange in as his apprentice.

Now, anyone who’s watched the development of the Dr. Strange movie in the headlines knows Marvel eventually decided to cast Scottish actress Tilda Swinton—whose ginger hair, porcelain skin, ethereal blue eyes and upscale Harrod’s-greeter accent make her perhaps the whitest of all possible casting choices—as its cinematic version of the Ancient One.

After an outcry led by the Asian American community, the cast, crew, and executives behind the film began offering up excuses.

Terrible ones.

First, Swinton told The Hollywood Reporter that the interpretation of the character in Strange was not intended to be Asian or male at all. “[The Ancient One] is not actually an Asian character—that’s what I need to tell you about it. I wasn’t asked to play an Asian character, you can be very well assured of that.”

But why was the Ancient One was being reimagined as non-Asian, then? Director Scott Derrickson said it was because the original character was itself offensive: “We weren’t going to have the Ancient One as the Fu Manchu magical Asian on the hill being the mentor to the white hero. I knew that we had a long way to go to get away from that stereotype and cliché.”

Forget that Fu Manchu was a villain, not a guru—Derrickson’s response begged the subsequent question of why the Ancient One couldn’t simply be written as a non-stereotypical Asian character.

He had an explanation for that as well: “As we started to work on it, my assumption was that it would be an Asian character, that it would be an Asian woman…. We talked about Asian actors who could do it, as we were working on the script, every iteration of it—including the one that Tilda played—but when I envisioned that character being played by an Asian actress, it was a straight-up Dragon Lady… I just didn’t feel like there was any way to get around that because the Dragon Lady, by definition, is a domineering, powerful, secretive, mysterious, Asian woman of age with duplicitous motives—and I just described Tilda’s character. I really felt like I was going to be contributing to a bad stereotype.”

In other words, Derrickson decided to cast a white woman in this prime role because he couldn’t imagine any version of the role that wouldn’t be offensive to Asians. As a result, he turned the Dragon Lady into a Celtic Tiger. (Oddly, the filmmakers were able to rewrite the equally stereotypical, but much smaller role of Wong the Manservant in a way that accommodated the criminally underused British Chinese actor Benedict Wong—so we do know such feats of scripting sorcery are possible.)

Meanwhile, Derrickson’s co-writing partner C. Robert Cargill dropped another flashbomb with his uncensored comments about the casting decision: He said the studio was afraid of alienating China, the second-biggest movie market in the world.

So here’s the question I want to pose to Derrickson, to Marvel Studios and to Hollywood in general. Let’s accept the curious premise that you couldn’t possibly have written the Ancient One in any way except in one that ended up with Swinton in the role. And Swinton is good in the movie—she’s a good actress, so that stands to reason. But she’s not a trained fighter, and for a non-stop action film, she has no transferable martial arts experience.

But if you had to rethink the Ancient One as a Celtic mystic, why keep the storyline set in the mist-shrouded landscapes of the high Himalayas? (To evade potential Chinese critiques, the movie has been controversially relocated to Nepal rather than Tibet, but even in China audiences will be hard-pressed to tell the difference.)

Why engage in the bizarre and unexplained pantomime of placing a white guru in a cultural and societal landscape that makes little sense plot-wise, and does nothing but provide you permission to incorporate orientalist exotica—chanting monks, dusky faces marching in procession, elaborate mandalas and temples and artifacts with spooky, tongue-twisting names?

The end result is maddening. There’s some terrific stuff in the film. The visuals are stunning. The action, as noted, is pulse-pounding and mesmerizing, even if it substitutes CGI, stunt doubles, and camera tricks for authentic cinematic combat because of the limitations of its cast. But Swinton’s bald-headed, saffron-dusted appearance in Southeast Asia is jarring, and the lack of narrative definition around her presence is glaringly obvious.

It’s a storytelling misstep that could’ve easily been fixed in way that preserved the filmmakers’ vision while transforming the movie into a historic Hollywood breakthrough. If they were determined to cast Swinton as the Ancient One, they should’ve cast a Chinese actor as Dr. Strange.

Now, Benedict Cumberbatch loyalists are undoubtedly going to go ballistic over this suggestion. (For what it’s worth, he’s great in the movie, although the British actor’s American accent is painfully forced throughout.) But let’s take a look at this from a purely business and narrative standpoint.

While the movie is poised for boffo box office receipts, Marvel Cinematic Universe movies are not at all dependent on star power. Indeed, the MCU’s signature move is taking lesser-known character talent and putting it in showcase roles, because the writing and special effects and comic book extravagance of their films allow audiences to revel in performances that aren’t anchored in “superstar” resume. Robert Downey Jr. brought his career back from the abyss by playing Iron Man, and Chris Evans had already been in a failed non-Marvel Studios superhero film, Fantastic Four, before being handed Captain America’s shield.

In short, MCU movies are the ideal vehicles for the creation of stars. And Dr. Strange was the ideal vehicle to create an Asian “movie star,” the lack of which that Hollywood has been musing over for decades.

Let’s review. First of all, Dr. Strange is a world-class physician. Casting a neurosurgeon as Chinese or Chinese American is hardly implausible. In the comics, he looks like a dark-haired, goateed man of no explicitly defined ethnicity. In fact, given his appearance, anyone could be forgiven for thinking Strange is Asian already.

From a financial standpoint, having a hero of Chinese ethnicity would set the world’s second-biggest (and most profitable) cinematic market on fire. Yes, they’re happy to watch white people on screen—the movie has earned $84 million so far in China, topping the box office for two weekends in a row.

But in China Strange is currently running behind Now You See Me 2 (which featured Taiwanese pop star Jay Chou); well behind the Jackie Chan/Johnny Knoxville’s actioner, Skiptrace, which hasn’t even been released in the US; and even behind the execrable Warcraft animated film, featuring Daniel Wu, Chinese American turned greater-China superstar. Imagine what a full-blown Marvel Cinematic Universe movie with a Chinese protagonist might have done at the box office.

As for Swinton and the inexplicability of her presence in Asia, an Asian Dr. Strange could’ve truly pulled a rabbit out of a hat, with a radical inversion of its storyline that actually makes complete sense.

Hear me out: What if Dr. Strange, 奇医生 (Qi Yisheng, literally “Dr. Strange”) was a Chinese American doctor on a highly publicized Doctor Without Borders volunteer stint in China—showboating his surgical skills for awestruck television cameras while “revisiting his roots.” Let’s say it’s all a part of a campaign to get him a cushy Sanjay Gupta-style talk-doc role on TV.

He loses the use of his hands in an accident, driving the mountainous roads of rural China, and his world comes crashing down. Desperate and with nothing to lose, he travels to the Emerald Isle on the advice of an Irish expat. There he is directed, with warnings, to the spectral far reaches of the country, full of standing stones and untouched forests, and ends up going “beneath the mountain” into the land of faerie, where he encounters the Queen of the Sidhe, the Ancient One, played by Swinton. 奇 ultimately realizes that the philosophy of the fey is similar to that of his ancestral culture’s Taoist beliefs. That one must achieve balance. That one cannot give without taking, or take without giving.

Dormammu, the movie’s villain, is the “one who takes without giving.” And the sacrifice that 奇 ultimately makes to defeat Dormammu is to give up use of his hands in exchange for taking the power needed to stop him. That’s a story that makes sense. And undoubtedly would make money.

Sadly, a risk-averse Hollywood is undoubtedly going to instead take Dr. Strange’s success as an affirmation of its business-as-usual white-hero-normative approach to storytelling.

Meanwhile, this past weekend saw the release of the first full trailer for Hollywood’s live-action cinematic adaptation of Masamune Shirow’s cult Japanese animation franchise Ghost in the Shell. The film stars Scarlett Johansson as Major Motoko Kusanagi, though they refer to her simply as “the Major” as a discreet acknowledgment of yet another casting outrage. At one point, DreamWorks and Paramount had apparently considered using CGI to “Japanize” Johansson, and thankfully thought better of it. As it is, the trailer’s depiction of Johansson and other white characters in an otherwise Japanese world—complete with jet-black dyed hair and updated traditional Japanese outfits—plays cosmetic chicken with yellowface.

Like Dr. Strange, Ghost in the Shell ecstatically brings us into an alternative cosmos in which everything is Asian, including its thugs, villains, and window-dressing background characters, but the most prominent protagonists are uniformly white.

Is there a mystical sling-ring or cybernetic uplink that can free us from this bizarre parallel dimension? Time, and more importantly money, will tell.