America prides itself as the “land of opportunity,” where all it takes to get ahead in life is hard work. But Donald Trump’s election victory revealed that many people believe they aren’t reaping the rewards they feel they deserve.

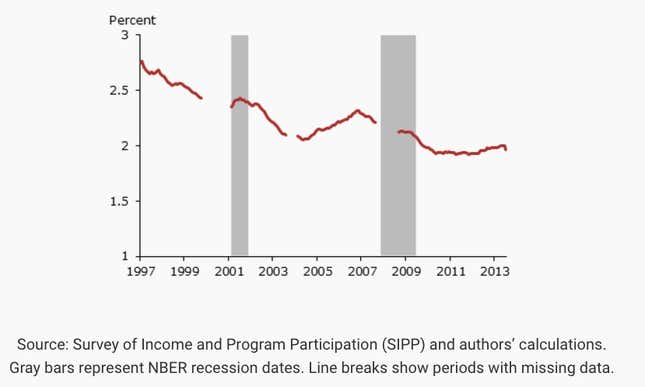

They have a point, according to the job-to-job transition rate. This somewhat obscure economic indicator measures how often people move from one job to another without a spell of unemployment in between. These moves reflect a healthy economy with opportunities for the upwardly mobile, as people tend to change jobs this way for higher pay or to learn new skills. In the US, this rate has been falling for almost two decades, according to researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

Using data from the Census Bureau, Canyon Bosler and Nicolas Petrosky-Nadeau show that between 1997 and 2013, the share of workers switching jobs from one month to another fell from almost 3% to 2%—about a 25% drop in relative terms.

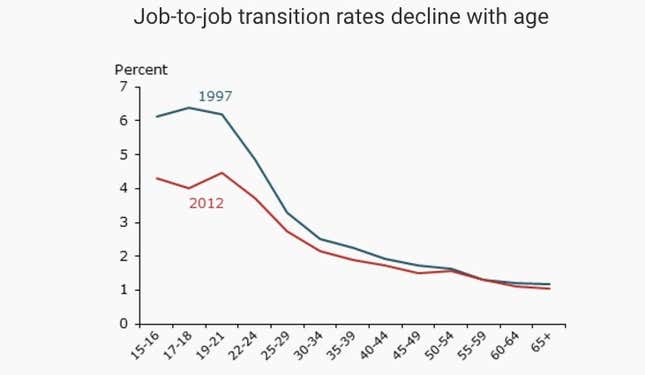

Bosler and Petrosky-Nadeau’s research also finds that the decline in the job-to-job transition rate has been much worse for people under 30. For older age groups, it hasn’t changed much since the 1990s.

Bosler and Petrosky-Nadeau are only able to speculate about the causes of the decline, a conundrum that several other academic studies this year have attempted to figure out.

Stephan Danninger, an economist at the IMF, published a paper in June (pdf) showing that people were switching jobs less often in all age groups and across all education levels. But demographic changes, including the aging of the labor force and changes in education levels, didn’t explain the decline.

The link between job mobility and social mobility is also tricky to measure, but there is probably some connection. As Danninger explains it, declining job mobility is likely a barrier to upward social mobility, because many people change jobs for higher pay.

But it’s more complicated than that. Danninger’s research suggests that since the financial crisis, low-skilled workers have suffered the worst decline in job mobility. So even if sluggish job turnover impacts the economy as a whole and everyone’s wages grow more slowly, it’s relative position that matters. “If that unwillingness to change jobs is more prominent among some subset of workers—let’s say the unskilled—then it would hurt those more than others and they might perceive it as a loss in social mobility,” he says.

One theory about why labor mobility is declining may also shed light on the source of slowing social mobility—or at least the perception of it.

Like the other studies, recent research led by economists at the Federal Reserve in Washington, DC found that labor mobility has been broad based, affecting all types of workers and industrial sectors. This study also argues that the decline began all the way back in the 1980s—mobility has diminished by between 10% and 15% since then, according to a comprehensive set of measures.

The Fed researchers dismiss the notion that a lack of job-hopping is for positive reasons, such as better matches between workers and firms, better pay, and better on-the-job training. Instead, they say there is some evidence that a decline in “social trust” has made people less willing to change jobs as readily as before.

“States with larger declines in the fraction of people who think that strangers are trustworthy have also experienced larger declines in labor market fluidity,” according to the research. People with smaller social networks have to rely on more costly, formal methods to find new jobs, while a lack of trust also makes employers more risk averse in the hiring process.

These cultural factors can stoke fears about lost opportunities, as much as an actual decline in social mobility might. That’s why some voters may have been drawn to Donald Trump, who blames immigrants and free-trade deals for taking locals’ jobs and, by extension, impeding their social mobility. But to some extent what people are experiencing is a lack of movement in the labor market, with non-economic factors playing a role.

Regardless of the cause of the decline, the implications are far reaching. Lower mobility in the labor market means workers have fewer chances to negotiate a better deal. Not only is this bad for workers, but it can hurt productivity. If fewer people move between industries, it could make the US economy less dynamic and responsive to new growth opportunities. Then, everyone is worse off.