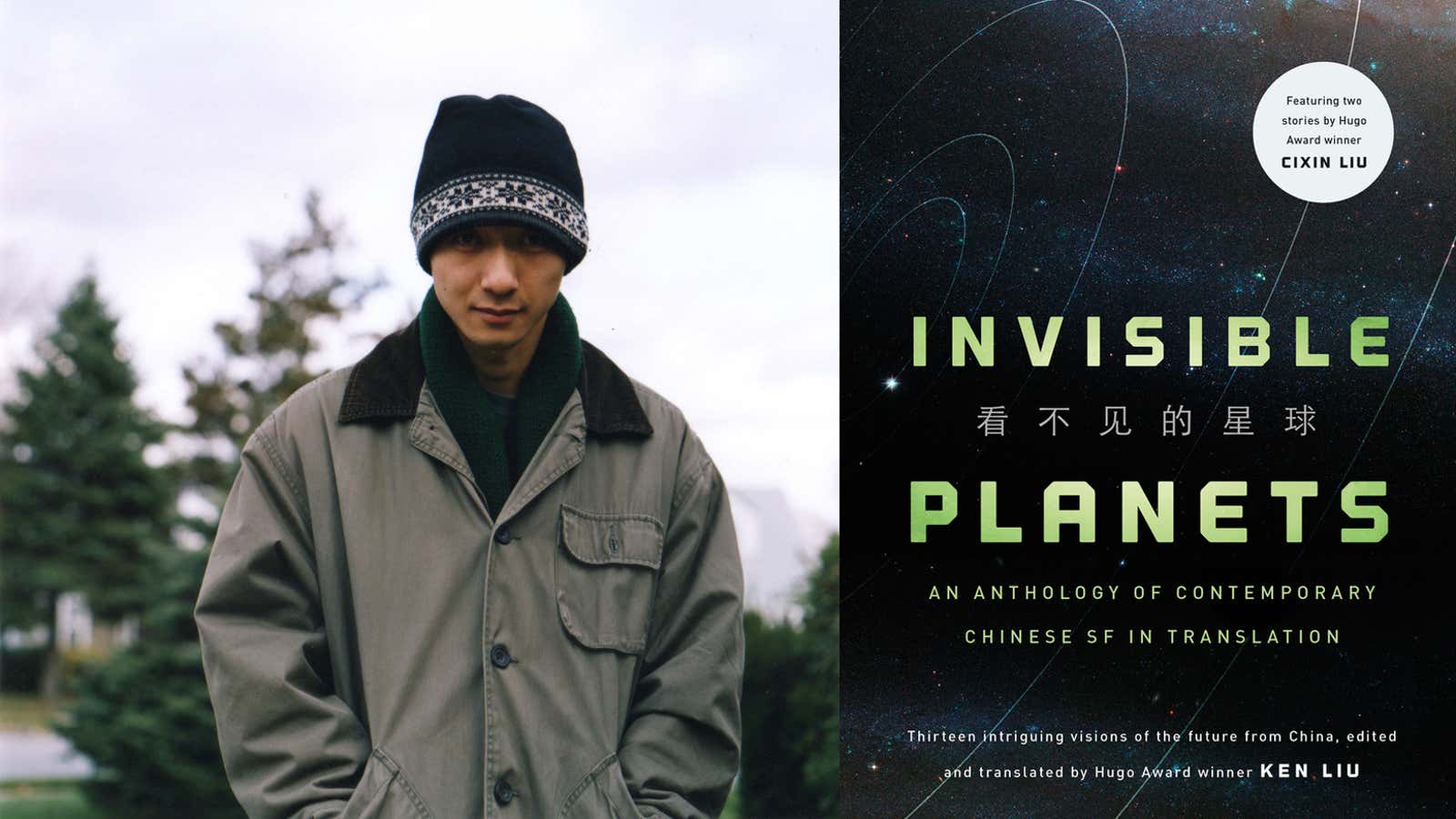

In 2015, The Three-Body Problem by Liu Cixin became the first translated novel to win the Hugo Award, one of the highest honors in sci-fi. A surprise hit inside and outside China, the book left English-language readers unsure about where to get more Chinese sci-fi. Now, Three-Body Problem translator Ken Liu is here to help: His new anthology, Invisible Planets, is a collection of excellent contemporary Chinese sci-fi short stories, by seven different authors, in English translation.

Liu and I discussed Invisible Planets, the process of translating sci-fi, and how Chinese authors see the future, at New York’s Book Riot Live festival in early November.

Quartz: When people outside of China are introduced to “Chinese sci-fi,” an initial reaction might be to ask, “What’s the difference between Chinese and Western sci-fi?” Is that a useful question?

Ken Liu: No, not really. You know, if you ask one hundred American authors, “What is unique about American sci-fi versus sci-fi written in the UK,” you’re going to get one hundred different answers. I think if you ask one hundred Chinese authors the same question, you’ll get one hundred different answers as well.

What tends to happen when people talk about Chinese sci-fi in the West is that there’s a lot of projection. We prefer to think of China as a dystopian world that is challenging American hegemony, so we would like to think that Chinese sci-fi is all either militaristic or dystopian. But that’s just not the reality of it. That’s just not how people in China think. To them, the West is the dominant force in the world, and they have to make do as a peripheral culture trying to reemerge from centuries of historical oppression and colonial dominance to take their place on the world stage. Trying to project our expectations and our desires onto the sci-fi being written in China now isn’t terribly helpful.

QZ: You’ve got a really wide range of authors and themes in your collection Invisible Planets. Could you pick out a couple to give people a sense of what’s in there?

Liu: Sure, yeah. One author that I like a lot in the anthology is Chen Qiufan. He’s a fascinating figure. He’s very linguistically talented, his English is excellent, and he speaks Cantonese as well as Mandarin and his topolect [a regional language]. He’s lived all over the world and worked at big tech companies including Google and Baidu. So he has a very worldly, cosmopolitan personal background.

When you read his fiction, his being erudite in both Western and Chinese traditions is very evident. He tends to make references to contemporary Western theory in sociology, psychology, and science, as well as classical Chinese poetry, sometimes within the same paragraph. Translating him is often quite a challenge.

He has this amazing voice—very wry, very mordant, very sharp. He has a great way of observing the situation and coming up with just the right way to get you to see the reality of it. He often writes tales that do feel superficially dystopian, about the state of China’s future and development. He has a lot that could be read as subversive commentary on China’s imbalanced development and political oppression. But at the same time there’s also a hope for change, for the ability of society to evolve and move forward, to emerge from that darkness. Overall the tone of the stories may come across as cynical and cold, but underneath there’s a humanistic heart.

QZ: I read two or three of the Chen Qiufan stories in the anthology, and I laughed the hardest I have in a long time.

Liu: Oh good, good! Right, they are hilarious. He’s got such wit in his stories. You have scenes that are so absurd and so funny. He really captures that absurdity well.

Xia Jia is another author who I think readers would really enjoy getting to know better. She is a scholar of sci-fi—in fact one of the first, if not the first, person to obtain a PhD studying sci-fi in China.

She tends to write in a style that’s very distinct to her. Chinese fans describe her style as “porridge sci-fi.” This means it’s not “hard” sci-fi—because it’s not all about engineering and calculations and so on—but it’s Ray Bradbury-like in the way that she uses sci-fi metaphors to get at deeper questions about the human condition.

She writes these wonderful stories that talk about how traditional Chinese values can evolve or coexist in a technologically advanced, futuristic world. One of these values is respect for the elderly. That is a theme in a lot of her stories. Tongtong’s Summer, which is in the collection, is a story about exactly that. It’s about the elderly and the difficulties they have in a cosmopolitan, contemporary world in which their children are super busy. They have a hard time finding a role in the extended family, now that the children are constantly working and there are no longer four generations living under the same roof.

The story really is about how the elderly manage to find a way to solve this problem, to solve their loneliness, their feeling of being useless and passed over, of waiting to die. The elderly use technology to overcome that by reaching out to each other and helping each other. I think it’s a wonderful vision, an amazing story about how, ultimately, it’s up to each of us to use technology to find the path forward for ourselves.

QZ: This is always an issue in translation, but with Chinese there’s often an assumption that the reader has a certain set of historical knowledge, or cultural knowledge. Is it right to say that this is a particular problem with Chinese? And how do you deal with it?

Liu: I don’t think it’s a particular problem with Chinese. If you try to read a translation of the Iliad or the Odyssey, you have the same issue. The distance between contemporary American culture and classical Greece is so large that, even though all of us are educated to some degree in classical Greek myth and the more well-known works, if you read a translation of the Iliad or the Odyssey, you’ll be lost. There are references upon references to, you know, the seventh monster in birth by the second goddess who came out of the second creator of the Cosmos, or something like that. And you’re expected to know exactly what that kenning is referring to, to be able to make sense of the line.

This is not something unique to the classical Greeks or classical Chinese. We do the same thing. People my age might say something like, “oh that looks like Rachel’s hair.” You might know that means Rachel from Friends, and what particular hairstyle that refers to, but go to a younger generation, or to somebody who hasn’t seen Friends, this would sound like nonsense. What is this an allusion to? We do that all the time, we make shortcuts, we make cultural references.

The issue is that, because China has a very long, deep literary tradition that is largely unknown in the West, when writers make these references to the classical tradition, it’s very hard to render the meaning in translation. We don’t get the impact of it. Just like when you’re reading the Iliad and you see the reference to some minor deity and you have to read the long footnote and you’re like, “Ok, what am I supposed to get out of that.”

I don’t have a good way to deal with it. I know that traditionally some people like to do this thing where you substitute a cultural reference in the target culture with one that is similar to the original reference, and hope that the reader will get it. For example, in Chinese, when you describe a man as being very handsome, you would say mao ruo Pan An.

What that means is the man “looks like Pan An,” a famous historical figure known for being like the Edward Cullen of his day. So when you translate that into English, some translators would advocate that you render that as, “he was an Adonis,” because Western readers would get that meaning. I generally don’t like doing that, because I think it is misleading. It often brings in allusions and semantic references that are not intended, and it often creates a confusion in the reader’s head about what was actually meant.

My preference is to try to explain the reference as much as I can in the text, and if I can’t, drop a footnote and hope that readers who are really interested will be able to look it up on Wikipedia, or on the web in general, and find out.

QZ: Chinese literature has a famously long history, but how can we trace the history of Chinese sci-fi?

Liu: Well, it depends on what you mean by “Chinese” and what you mean by “sci-fi.” If you construct the English canon, you say, “Well we can start with Beowulf.” Unfortunately Beowulf survives only because of this manuscript that was rediscovered by luck. So arguing that it’s the root of English literature is somewhat problematic.

Chinese sci-fi is the same way. Sci-fi, as we understand it, is an invention of 19th-century Europe, chiefly the UK and France in the industrial revolution. Books by Verne and Wells made their way first into Japan, and then via Japan into China at the very end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th Century. These translations were done by some of the most famous writers in vernacular Chinese.

I think in some ways the translation work they did was related to and relevant for the task of constructing the vernacular literature. And so these earliest translations of Western sci-fi ended up inspiring the first written works of sci-fi in Chinese by authors in China. Some of them are derivative of their western models, and some are quite original. For example, Tales of the Moon Colony is often considered one of the first original works of Chinese sci-fi. That was done in the first decade of the 20th century.

But even though we sort of think of that era as the beginning—with this wave of translations and original creation—a lot was forgotten. So it’s not really accurate to call those the “root inspiration” of Chinese sci-fi either. They were there, yes, but many were rediscovered later on, and were not influential for writers during the 1950s and 60s.

QZ: What is different about translating sci-fi, versus other genres?

Liu: You know, that’s interesting. I think that what’s unique about sci-fi—at least from the view of a lot of Chinese writers—is that sci-fi is least-rooted in the particular culture that they’re writing from.

There’s a phrase among Chinese writers that says, “there are no glazed tiles on Mars.” What it means is this: Chinese palaces, traditionally, are covered with glazed tiles, or glazed shingles if you will. The point of the phrase is, when you go into space, you become part of this overall collective called “humanity.” You’re no longer Chinese, American, Russian, or whatever. Your culture is left behind. You’re now just “humanity” with a capital H, in space.

Now of course, for most of us, and also I think for most Chinese readers, that kind of ideal is not necessarily desirable and is simply impossible. How can we possibly imagine a future without reference to where we are now? Maybe there will be no glazed tiles on these Martian structures, but there will be concepts of Western privacy, of Western division of structures into rooms, there will be all kinds of things that are clearly influenced by the culture from which the astronauts originate. The idea that somehow the way forward is to abandon the past, to me, is preposterous, and both undesirable and unrealistic. But I get the sense that at least a significant minority of Chinese writers really do push for that vision.

For a lot of Chinese writers, their view is that sci-fi ought to be the easiest genre to translate because it relies the least upon culture. I have found that not to be true.

QZ: Do you think that sci-fi in translation is a good way for Western readers to begin to understand Chinese literature?

Liu: That’s interesting. I really question the extent to which Chinese sci-fi is a good representation of Chinese literature.

To give a little background, most Chinese literature these days is written in what’s called modern standard written Chinese, which is very different from classical Chinese. It’s a new language as far as literature is concerned. It has a history not much longer than 100 or 120 years.

Because it’s a relatively new language, the literature written in it shows all the same kind of roughness and unsettledness and complexity that you would expect of a vernacular literature still young and in development. Just as English and French literature went through centuries of instability when they were first being written in these vernaculars, as opposed to Latin.

The contemporary Chinese literary tradition is different from the classical one that came before it, too. Even though it draws on that classical tradition all the time, in the same way that the English language’s earliest vernacular works drew on the classical Latin tradition.

So what you end up with is, reading contemporary Chinese sci-fi is a good introduction to contemporary Chinese literature. It is, however, not necessarily a good introduction to “Chinese” literature, understood as a whole.

This transcript has been edited for concision and clarity.