Over a five-year period in the 2000s, Central Asia’s Fergana Valley saw two revolutions, the bloodiest government-ordered crackdown on protestors since China’s Tiananmen Square, and a wave of authoritarian abuses. The time was laced with geopolitical intrigue: The US had military bases in the region for the entire period, erected as supply hubs for the war in Afghanistan.

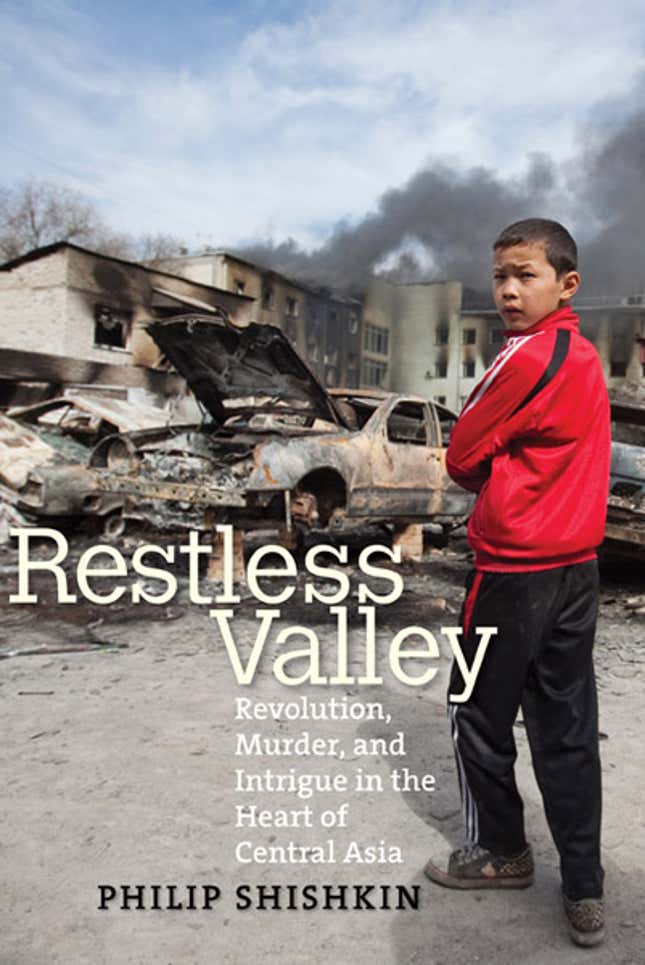

In his absorbing Restless Valley: Revolution, Murder and Intrigue in the Heart of Central Asia, Philip Shishkin reconstructs these events and others through the eyes of its participants. He succeeds, not by trying to provide a definitive or analytical account, but through an investigative eye for detail, probing interviews, biting wit, and insights refreshingly informed more often by references to contemporary popular culture than to the 19th-century travelogues that writers of such regional primers tend to fall back on.

The “restless valley” of the title refers to the Fergana, a densely populated agriculture-rich region straddling Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. Shishkin, who covered the region for the Wall Street Journal following the US-led military campaign in Afghanistan, begins his journey with the toppling of Kyrgyz president Askar Akayev in the “Tulip Revolution” of March 2005. Among the characters we meet are locally well-known personalities—Medet Sadyrkulov, who remarkably served as chief of staff to both Kyrgyz presidents before his death in a faked traffic accident in March 2009 as he turned opposition leader; and Gennady Pavyluk, a journalist and government critic who was thrown from a high-rise window in neighboring Kazakhstan, lured there by an email promising to fund his investigative reporting.

But the most poignant moments are portraits of previously unknown witnesses and victims. They include Rahima Mamajanova, pulling the sheets from the faces of more than a hundred dead bodies piled beside a road as she tried to identify her 16-year old son, who was killed by a hail of bullets from Uzbek security services in the May 2005 Andijan Massacre.

Restless Valley uncovers many of the informal networks and actors that permeate the region. Shishkin travels a heroin route in Afghanistan and Tajikistan, interviewing farmers and traders, police, couriers and border guards, and discovers creative smuggling techniques, such as a small motorized parachute loaded with 18 kilos of heroin that flies over the Panj river. He maps the shadowy financial networks of former Kyrgyz president Kurmanbek Bakiyev, showing how his family and business associates turned the nation’s main financial institution into a money-laundering vehicle with global reach, including Western correspondent accounts and political backers.

A key figure is Eugene Gourevitch, an “enterprising financier” who became a trusted confidant of the Bakiyev family, especially the president’s son, Maxim. Now in Italy facing charges related to offshore tax avoidance schemes, Gourevitch recounts to Shishkin how the overthrow of Bakiyev left him stranded in Bishkek, where he had to rely on a Chechen mafia to smuggle him and his family to neighboring Kazakhstan. From there, he joined the Bakiyevs in Minsk under the protection of Belarusian dictator Alexander Lukashenko before turning himself in to US authorities under a plea deal that led to charges against Maxim Bakiyev. (On May 10, a US federal judge dismissed securities fraud charges against Maxim, who lives in London.)

Shishkin has a keen sense for political relations and personal agendas, but he over-simplifies some key episodes, and omits others. For instance, he gives credence to a theory popular in the region that the United States actively supported the ouster of president Akayev in the Tulip Revolution. But he does not explore similar allegations that Moscow used “soft power” against the Bakiyevs five years later. The book explores in considerable detail the mysterious offshore companies that gorged on nearly $2 billion-worth of Pentagon fuel contracts for the US-run Manas Air Base, including allegations of their corrupt ties to the Bakiyev family and US intelligence. But he offers no comparable insights into the logistics contracts of the Northern Distribution Network that traverses neighboring Uzbekistan, and which have netted the Central Asian countries more than $500 million in transit fees.

Similarly, a chapter titled “Restless Valley” recounts bloody clashes between ethnic Kyrgyz and Uzbeks in June 2010 in the wake of Bakiyev’s toppling. That fighting claimed some 400 lives, dislocated tens of thousands, and destroyed 2,000 buildings. Shishkin persuasively characterizes the interim government as “too weak and incompetent to prevent the outbreak of violence.” But he refers to the violence as a “civil war.” The term seems to suggest organized and armed combatants on both sides, but is inappropriate given the relative defenselessness of the Uzbeks. Several external observers have instead called the episode a pogrom to emphasize complicity by the local Kyrgyz government, including its security services. While Shishkin skirts the politically fraught issue of culpability, he does recount the plight of Azimjon Askarov, an Uzbek Kyrgyzstani human rights advocate who was jailed for life while documenting the violence, mostly on evidence provided by Kyrgyz police in a flawed trial.

Ultimately, the restless valley in Shishkin’s fine book emerges not as a smoldering isolated area, as it is commonly portrayed, but as entangled within a web of regional networks that have helped to stoke political and social unrest. He is wise to refrain from speculating about the future of the region, especially in light of the coming drawdown of NATO forces. But his own compelling portrayal of the major episodes of 2005-2010 suggest that the underlying sources of volatility remain.