Since the election of Donald Trump, the controversial term “alternative-right” or “alt-right” has emerged in mainstream media to describe a loose configuration of people who rally behind incendiary, white nationalist polemic in the US.

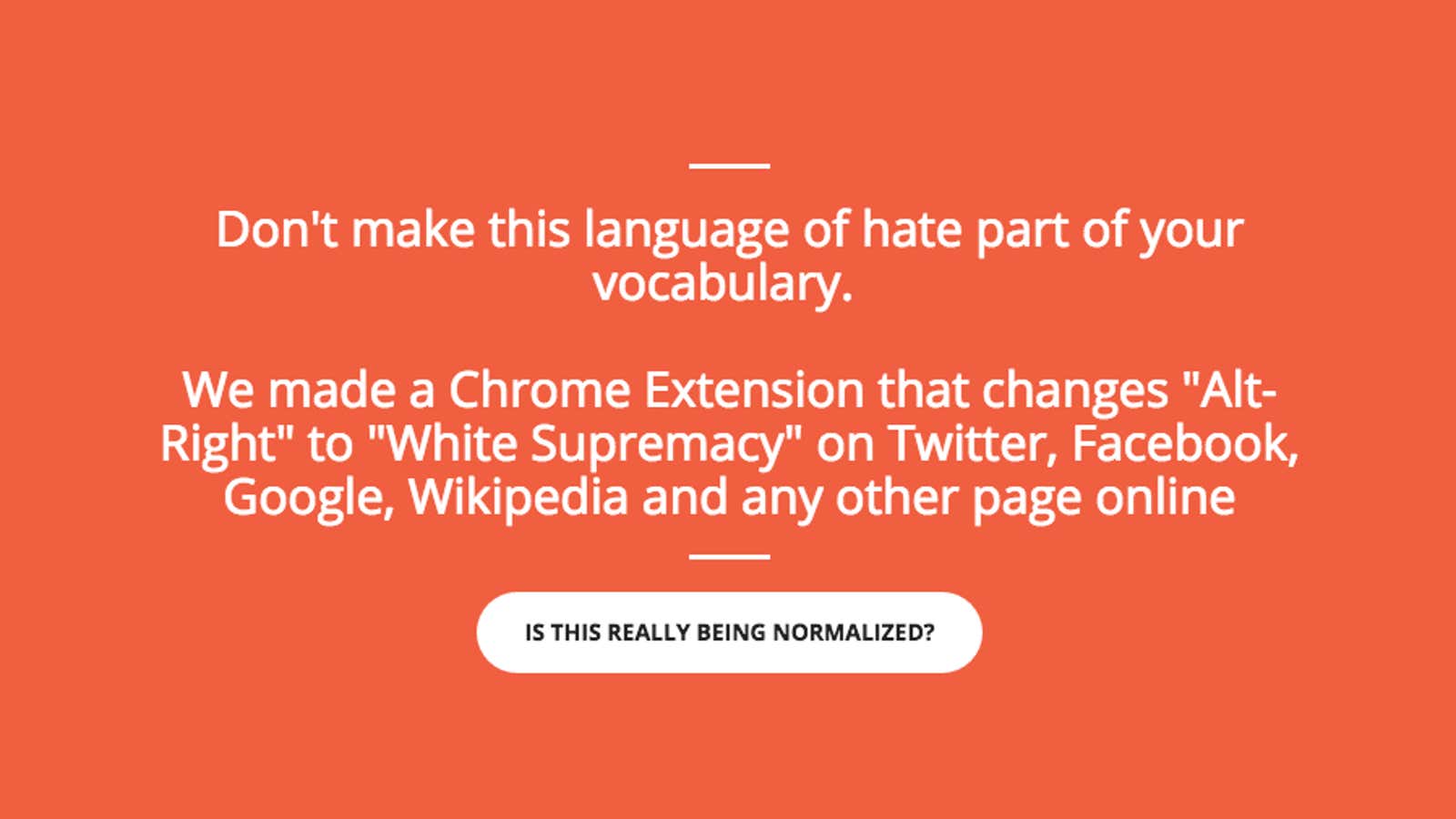

But an anonymous New York City-based activist says that the use of “alt-right” instead of “white supremacist” is nothing more than “linguistic sanitation,” and has created two Google Chrome extensions to fix that. The extensions automatically replace all instances of the term “alt-right” on the internet with “white supremacist” or “Neo-Nazi.”

“This gentle sounding name is the rebranding of White Supremacy and White Nationalism, and its normalization must be stopped,” the designer, operating under the pseudonym George Zola wrote on their website.

They are not the only one to call out the term “alt-right.” On Nov. 28, the AP updated its style guide stating that “alt-right” should only be used in quotation marks and with a definition. In a blog post, John Daniszewski, AP’s vice president for standards noted that the news agency has simply described such beliefs as “racist, neo-Nazi or white supremacist” in the past.

The term “Alternative-Right” originates with Richard Spencer, president of the far right advocacy group National Policy Institute (NPI) who used it in a speech in 2010 speech and recently led members in a “Hail Trump” salute, as the Atlantic captured on video. It was propagated by fringe media exec Steve Bannon, now a senior strategist for Trump.

The free web browser extension for “white supremacist” was downloaded 1,200 times on its first day, Nov. 16. As of Nov. 29, links to the extension had reportedly been shared 63,000 times on Facebook.

Zola tells Quartz that they developed the Neo-Nazi version in response for a clamor for the more loaded term. The designer is now focusing on getting the extensions ready for FireFox and Safari.

“I’m not sure how much further we’ll take the Chrome Extension approach, we have larger goals of making noise,” Zola explains. “Any way we can prompt conversation and get people to consider the importance of their own word choice as well as question the word choice of the media is what we’re aiming for.”

Zola also shares that the response to the project has been shockingly positive: “When we started this, I expected a lot of hate mail. However, the response has been overwhelmingly positive and personally touching.” The project has even drawn out personal stories from those affected by Nazi occupation. “We’ve received messages of hope…we’ve inspired them by presenting simple yet powerful messages of defiance.”