In the film Arrival, Amy Adams plays a linguist charged with figuring out how to communicate with aliens who have landed on Earth. Visually, the aliens—called heptapods—are a testament to masterful movie magic: Everything from their subtle, fluid movements to the dense atmosphere in which they breathe fits with our idea of biological possibility. These otherworldly life forms seem truly feasible, even real.

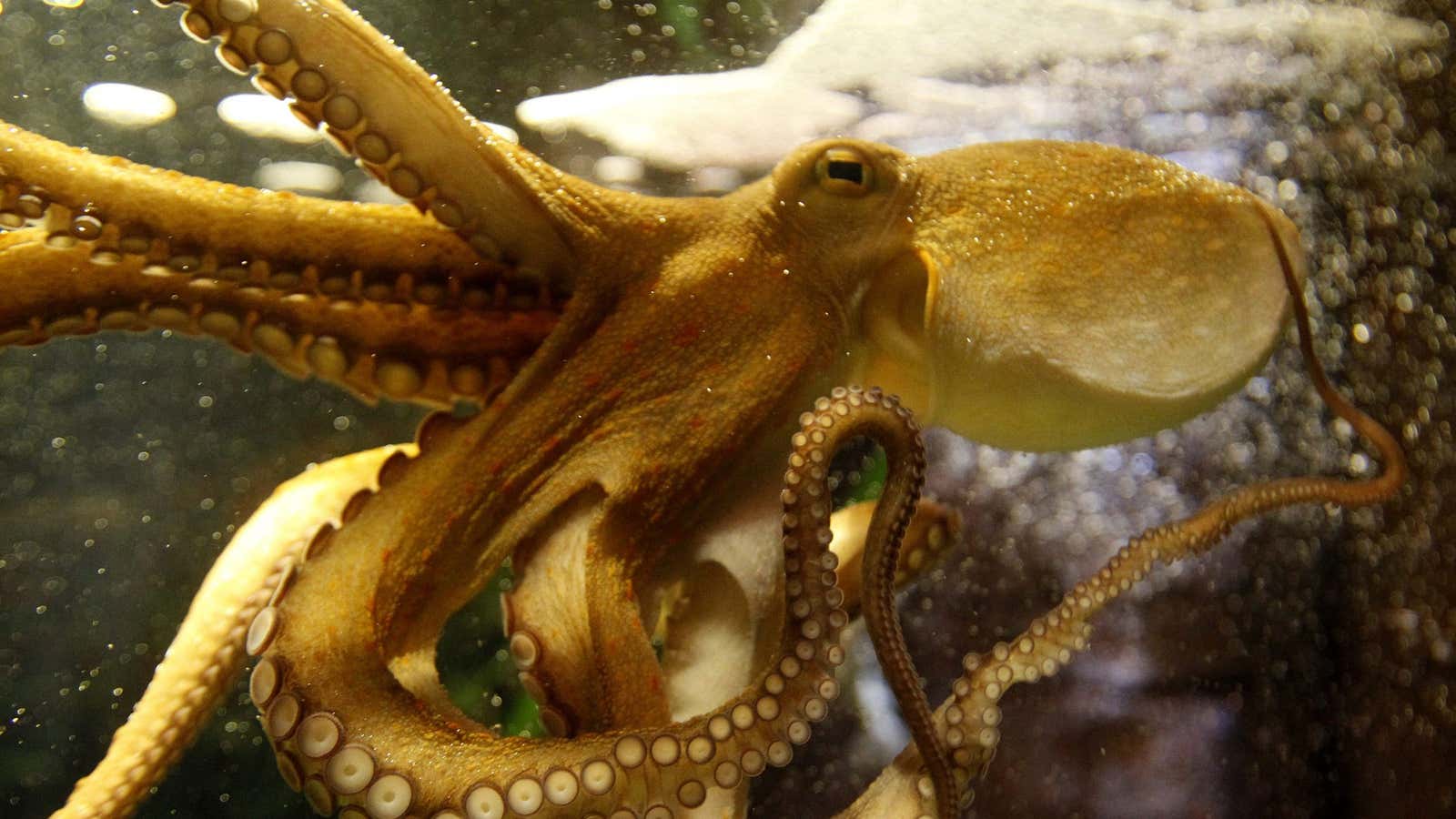

But perhaps what makes the heptapods in Arrival most believable is that they are not all that alien to begin with. From their body shape to their tentacles to their ability to squirt an ink of sorts, heptapods bear a strong resemblance to Earth’s most alien intelligent life: cephalopods (squid and octopus).

“The big eyes, outreaching and slithering tentacles and boneless body of the cephalopod make for good horror,” says Eddie Bullard, a historian specializing in UFOs and aliens. “They do indeed seem alien in the sense of very much unlike us, utterly different and without any empathy or common ground.”

Our species has always been fascinated by the idea of alien life. Centuries before Jesus Christ was born, scholars suggested life might exist on other worlds, including our own moon. Given the alien nature of octopuses and their relatives, it perhaps comes as no surprise that they have inspired creative minds. The 19th-century author Camille Flammarion described a planet full of perpetually swimming, tentacled seal-like beasts, for example. And of course, every sci-fi enthusiast remembers the slimy, brown invaders with their “Gorgon groups of tentacles” brought to life in H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds. But besides these few exceptions, before World War II, the imaginations of science fiction authors rarely strayed far from humanoid reality. Tales of the extraterrestrial generally consisted of green or grey men with large eyes from planets within our solar system.

It wasn’t until after the 1940s that science fiction exploded with a diversity of peculiar alien forms. Octopoid creatures have since become fan favorites. From the cartoonish Zoidberg (Futurama) and Kang and Kodos (The Simpsons) to the aliens of Prometheus and Arrival, modern storytellers seem particularly fond of drawing upon the deep for inspiration.

In many ways, it makes sense to use the squid and octopus as models for alien life. The oceans are like an alien world, with an atmosphere we cannot breathe that gives birth to bizarre forms beyond our imaginations. And cephalopods are about as far from the classic mammalian arrangement as you can get—yet they display surprising intelligence. Octopuses use tools; they play; they can solve problems and puzzles; and they may even engage in warfare with improvised weapons. They are the only invertebrate that displays a level of thinking scientists ascribe to consciousness. Indeed, any aquarist who has attempted to keep such creatures in captivity learns quickly just how smart these animals are and just how much work is required to keep them happy and healthy.

Individuals exhibit different personalities, with some that are cooperative and friendly and some that are markedly not. Researchers have also found that without enough mental stimulation, captive octopuses quickly become distressed and even harm themselves—not entirely unlike the behavior that we humans exhibit in response to solitary confinement.

And so what makes these animals such ideal models for alien life is that their intelligence, which some researchers believe is on par with our own, is still foreign to us. For example, their minds aren’t completely centralized in their walnut-sized brains—scientists have shown that octopus arms can “think” independently, not only moving when separated from the body but performing “thoughtful” actions like grasping food and directed movement. Each arm contains neurons that work without the oversight of their brains. We cannot imagine what it would be like to have autonomous limbs, as ours are so dependent on our central nervous system.

The differences between our minds and theirs are evolutionary. Cephalopod intellect evolved under very different conditions than most creatures we consider intelligent, like parrots or apes. Almost all the animals we consider smart are long living, social creatures whose intelligence was at least partly driven by the need to form complex relationships. Our minds were shaped to be able to remember individuals, keep scorecards of who has helped us and who has not, and maintain relationships that span of decades.

Cephalopods, on the other hand, live brief, antisocial lives. Even large species like the giant Pacific octopus last but a few years, and want little to do with other octopuses outside of copulation. Their minds didn’t evolve to form social bonds or lasting relationships. We don’t really know why they’re so smart or what evolutionary pressures led to their relative brilliance, though some think it may have to do with adapting to a life without a shell (an hypothesis that could also explain their short lifespans). Their intelligence, like their eight-legged, boneless bodies, is truly alien, even though both are from this world.

While cephalopods have inspired countless science fiction authors, it’s intriguing that they are almost entirely absent from abduction accounts. “I’ve seen no more reports of tentacles on UFO aliens than I could count on my fingers,” says Bullard. The aliens that show up in purported real-life encounters “are a bit like us… something we can relate to.”

Bullard hypothesizes that when it comes to face-to-face encounters with otherworldly creatures, most people would prefer “something at least a little like us.”

“Cephalopods may not offer that toehold of reassurance,” he says, “and we shy away from them in our imaginative creations, leaving such monsters to the movies.”