Squeeze your employees, and you’ll pay the price. Seems obvious—but Ernst & Young has actual evidence. For its annual fraud report the firm surveyed 3,000 company board members, managers and their teams in 36 countries across the world, and found that employees feeling the double pinch of increased demands and fewer financial perks are alarmingly likely to respond by doing anything from fudging the numbers to bribing officials and clients.

Practically everyone, it seems, is feeling the pressure to grow their businesses and meet their targets in a tough economic climate, but at the same time, “the vast majority” of people reported that they’re not getting the bonuses, raises and other perks that they used to. Oddly enough, this is true not just in the sputtering engines of Western capitalism but also in hyper-competitive rapid-growth markets “where the battle for talent remains fierce.” In India, for instance, 43% of respondents were witnessing what E&Y delicately describes as “downward pressure on pay and remuneration.”

“Greater pressure to deliver growth and downward pressure on reward can be a risky combination,” E&Y concludes. “Both pressures can, in some cases, drive actions that could damage the business, such as fraud, bribery and corruption.” Compounding that problem, E&Y said, is the fact that the twin focuses on growth and cutting costs—especially at the expense of employees—”can weaken the systems and teams in place to prevent and detect these actions.”

Unfortunately the report contains no specific data that might give the hard-driving manager a pointer as to just how much more sweat he can squeeze out of his employees before they start to cook the books. But it says that the pressure to perform can lead to various kinds of dubious conduct. For instance, employees feeling a financial pinch may either bend the rules themselves or turn a blind eye when others do so. E&Y notes that “an alarming number appear to be comfortable with or aware of unethical conduct.” In other cases, especially in rapid-growth markets, employees are willing “to make cash payments or offer personal gifts or entertainment to win or retain business.”

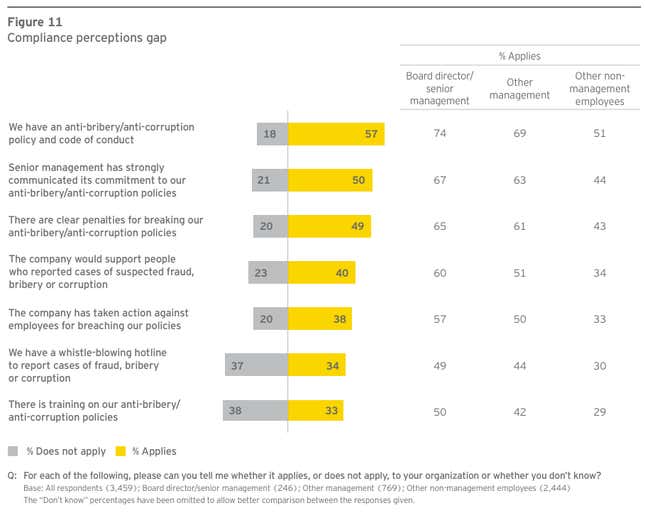

But company bosses would do well to note one thing: E&Y found that the higher up managers are—and presumably the more they are paid and get regular raises and bonuses—the bigger the “perceptions gaps” between them and other employees about how the company is dealing with corruption. Senior staff are considerably more likely to think the company has clear policies, training and sanctions for corruption than their subordinates do—which might mean they’re a little too trusting that such safeguards will catch things before they get out of hand.