It’s been a while now since I wrote this article on how Greece’s fertility bust and our unenlightened response to it helped build our mountain of debt in the ’80s and set us on course for the sovereign debt crisis of 2009. I’ve been thinking a lot about this issue of fertility lately, and I don’t like the economics of it. Especially the combination of debt rising exponentially and a population no longer on the increase.

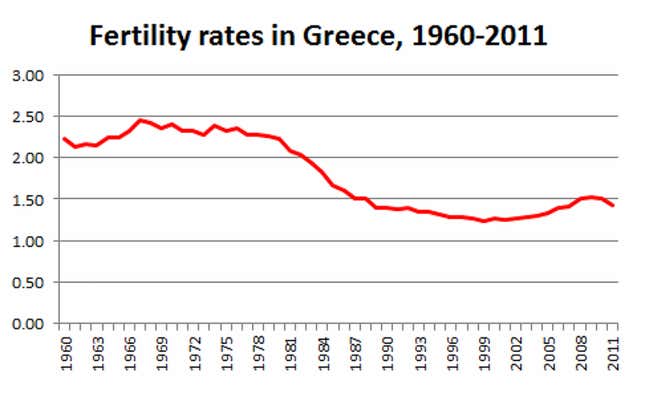

This is how I came across the near-mystery of the Greek fertility rate. You’d never guess it, but Greece’s fertility actually rate grew as we entered the recession in 2008 and continued to rise until 2011, when the last data were collected, and it remained higher than at any point during the ’90s. You can see the data for yourselves here. Fertility rose to levels unseen since 1987—an apparent reversal of a decades-long slowdown in fertility also experienced by most other European countries.

But look more closely (or perhaps, zoom out a little) and you’ll find that the reversal really started in 2000, and is reflected elsewhere in Europe. Eurostat explains it thus:

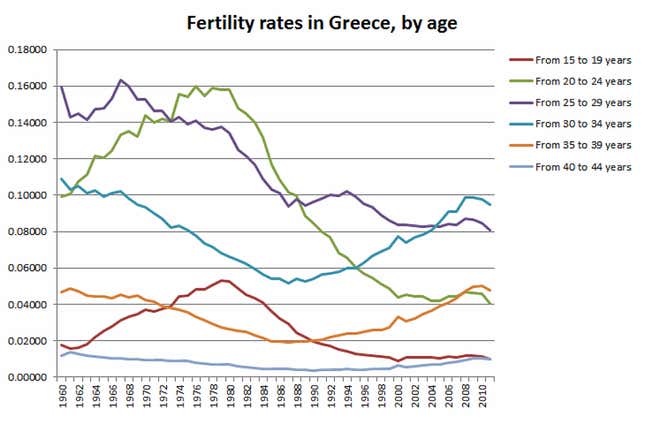

The slight increase in the total fertility rate observed in recent years may, in part, be attributed to a catching-up process following a general pattern of postponing the decision to have children. When women give birth later in life, the total fertility rate tends to decrease at first, before a subsequent recovery.

In particular, zooming in on women’s fertility rates by age group in Greece, it becomes obvious that what really happened since the naughties was that the persistent fall in fertility among women in their 20s paused briefly, while fertility rates among women in their 30s and 40s continued to rise. Both of these groups are now roughly as fertile as they were in the 1960s, thought for different reasons. Essentially, the long trend of Greek (and other European) women delaying their first births is slowly grinding to a halt, and we’re seeing the demographic equivalent of a dead cat bounce. The effects of the crisis, however, are also observable. Every age group has seen a dip in fertility since 2010, and they are likely to continue to do so.

One thing that’s interesting in studying demographics is to see how fertility rose and fell in different regions. Greece’s true demographic black hole is Western Macedonia, which managed to lose fertility even in the boom-times, and was among the worst-hit regions during the crisis. Unemployment there is the highest in Greece, at just over 30%, and most worryingly it is a border region, situated between Albania and the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. As more of our national politics turns to exploiting nationalism, this region is going to become a testing ground for all manner of extremist tactics.

On the other hand, Attica, Crete and the South Aegean did fairly well in terms of fertility, and unsurprisingly the islands in question had the lowest unemployment rates in all of Greece as of late 2011, which would explain some of their fertility performance (Attica of course boasts a mega-city, which tends to distort trends).

Stand by then, for the next chapter: the inevitable discussion about the link between unemployment and fertility.