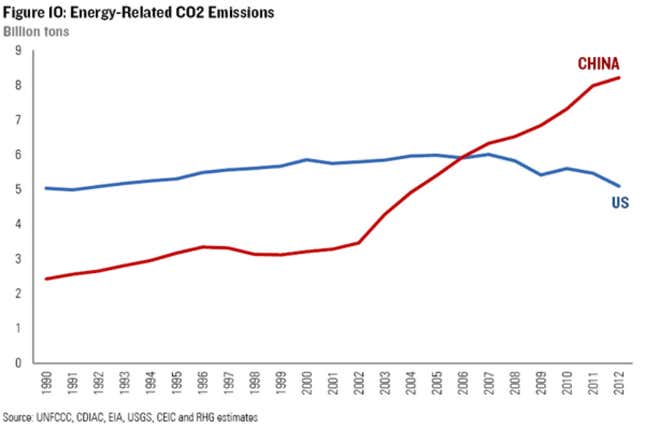

Environmental websites are buzzing that China, the world’s biggest emitter of carbon and other heat-trapping gases, is on the cusp of breaking the persistent logjam on global climate change policy by placing an absolute cap on its carbon emissions. Beijing’s impending move, writes Grist, would show that, compared with the US, “China is either the more mature of the pair, or just majorly sucking up to Mama Earth.”

The reports are inaccurate: Seven Chinese cities are enacting experimental carbon-trading programs as of 2014, and Beijing is fast reducing how much carbon is burned per unit of GDP (known as “carbon intensity”). But China hands in Beijing and the US tell me it has made no firm decision on capping absolute emissions. (The rumor began with a May 20 report by the reputable Chinese newspaper 21st Century Business Herald.)

Yet the hubbub underscores an expectation among environmentalists and others that Beijing is moving toward doing more to avoid the most catastrophic climate forecasts. Beijing already has ambitious goals for sharply reducing carbon intensity by 2015. Against the backdrop of rising local unhappiness with air pollution, China’s leadership has signaled the possibility of an even faster cleanup. Climate activists hope for another iterative jump by China—from a proportional approach to emissions reduction (reducing carbon intensity), to an absolutist strategy (a cap on total emissions).

“An absolute cap simply makes management simpler,” Deborah Seligsohn, a China expert at the University of California at San Diego, told me. “An intensity target depends on expected GDP, and so localities try to game it. They can’t game a cap.” That’s why a cap would be “a big deal domestically and internationally,” she said.

Since Deng Xiaoping launched China’s modern age in 1979, Beijing has prized economic growth over every other metric of success. No prominent expert believes that China’s emissions will decline this decade—David Fridley at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory told me that the only scenario for such a fast reduction is economic collapse or stagnation. The only hope is that China’s emissions growth can be tapered.

Many experts wonder how Chinese leaders will enact even the goals they have set. “Achieving these targets eventually would come at considerable economic cost, and so how China will strike a balance between local air pollution, which has become dire in some places, and the cost of controlling these pollutants is still unclear,” said John Reilly, an environmental economist at MIT.

Yet self-preservation is a powerful force. The tradeoff between economic growth and cutting emissions will become less stark if China’s leaders conclude that pollution is a serious political threat. Environmentalists are betting that China’s leaders will decide that it is.