The sociologist Robert Bellah once wrote that the real purpose of Memorial Day, a US holiday that’s celebrated this Monday and commemorates those who have died in battle, is to re-indoctrinate the American public into the “national cult.”

His point is that federal holidays serve to reinforce American values, which can be viewed as a kind of religion. If Bellah were writing about the subject today, he would certainly mention one ceremony conducted with religious fervor all over the country on Memorial Day: the barbecue cookout.

And increasingly, those Americans are cooking at the altar of the Big Green Egg.

Created in 1974, the Big Green Egg is a barbecue grill that can be used as an oven or smoker, as well. The design is based on slow-cooking clay pots from Japan that date back centuries and were brought to the US by American soldiers after World War II. The clay was ultimately ditched in favor of NASA-developed ceramics that can withstand much higher temperatures without cracking.

Emphatic users of the Egg, many of whom own two or three, are known as “eggheads.” They can be found contributing to online forums, proffering tips and recipes and gleefully extolling its virtues. It really locks in the moisture. It cooks so evenly. It smokes even as it grills. It can be used to make real Italian brick-oven pizza…

“Our customers are the best sales people,” says Jodi Burson, the product’s marketing manager. She says the privately held Big Green Egg Company has seen double-digit sales growth for over a decade, thanks to a cultish following that would be the envy of any business startup. So what is it about the Big Green Egg that inspires such passion?

1. It’s kitschy

The Big Green Egg has the name and appearance of a product that just might be marketed with the promise of changing your life for six easy payments of $19.95 (it in fact costs more.) But the Egg’s infomercial-like qualities actually seem to stoke, not dampen, the ferventness of its following.

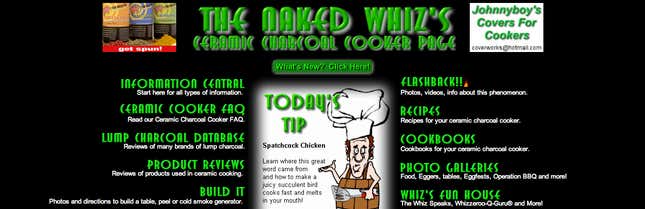

Images of “Eggfests”—official gatherings where eggheads get together to cook, including the annual Eggtoberfest—make the events look far tackier than the ceramic cooker itself. The same could be said of a lot of websites dedicated to using the Egg.

And then there’s the informal Egghead vocabulary, which consists entirely of egg-based puns. For eggsample. The company encourages this kind of word play by referring to its supplementary products as “eggcessories.” A collection of these terms can be found in the “eggictionary” section of a popular egghead forum. Eggheads adore the product’s kitsch.

But kitsch in and of itself does not a cult make. A product has to also be uniquely functional. The combination of the two seems to be the key. Take Crocs, the groan-inspiring foam clogs that come in an unlimited array of bright colors and that quickly rose to consipicuous popularity in the US. The footwear found an early following among backpackers, who need lightweight shoes to slip on at camp, and cooks (Mario Batali, famously), who simply want something comfortable to stand up in for hours.

2. It makes a statement

The Big Green Egg couldn’t have succeeded if it didn’t produce decent food; it’s just too expensive. Even the smallest model costs about $400. The large Egg is close to $800, more comparable to a high-quality laptop than a barbecue.

So, obviously, people buy their Eggs because it works well. But owning a Big Green Egg also makes a statement about how seriously you take barbecuing. This is important, since cooking out is such an American pastime.

The skilled preparation of meat—producing steaks or burgers that are exactly medium rare, roasting a turkey without drying out the breast meat, smoking a pork shoulder to perfect succulence—is highly venerated, especially among men. Cooking meat in an Egg signals dedication to doing it right, and it does so in a very public fashion.

3. It’s easy—but not too easy

The Big Green Egg is far from the only home appliance with an evangelical following. If you know anyone with a Dyson vacuum or Wolf stove, then you’ve probably been subjected to a fair share of proselytizing.

The Egg fits into a particularly special sub-category of appliances that don’t simply make life easier, but actually make it possible to create things in your own home that you couldn’t otherwise. Slow-smoked ribs. Neopolitan-style pizza. As a do-it-yourself appliance, the Egg is similar to a SodaStream, the popular and religously espoused counter-top device that lets you make carbonated water and soft drinks on demand.

The Big Green Egg markets itself as incredibly easy to use. “The first time you cook, you get great results,” Burson, the marketing manager told me. Others have more or less echoed that sentiment. A first time user blogged on Wired that “it took a little getting used to, but…within a week, we had it down to a science.”

But the cooker isn’t so simple as to make it impersonal. In a TED talk he delivered late last year about the psychology of motivation, Dan Ariely, a behavioral economist and the author of Predictably Irrational, told a story about the development of processed cake mixes. Early formulations required the baker to simply add water, but market research showed that left people unsatisfied. They didn’t feel like they had anything to do with the cakes they made. Removing the egg and milk ingredients from the powdered mix and requiring bakers to add those things themselves gave them a greater sense of accomplishment and ownership of the end result.

Egg users have a lot of control over what they do with their cookers, which is ultimately why there is a vibrant community of eggheads who share techniques and recipes with each other. The SodaStream may have its die-hards, but even the biggest fans probably wouldn’t know what to do with themselves at “Streamfest,” if such a thing ever happened.