This month, prime minister Shinzo Abe will begin unveiling Japan’s “national growth strategy,” the structural reforms from the “third arrow” of Abenomics. This will include a crucial one: boosting female employment. Already, Abe has called on corporations to have at least one female executive per company (paywall). The government also plans to open 250,000 daycares over the next few years.

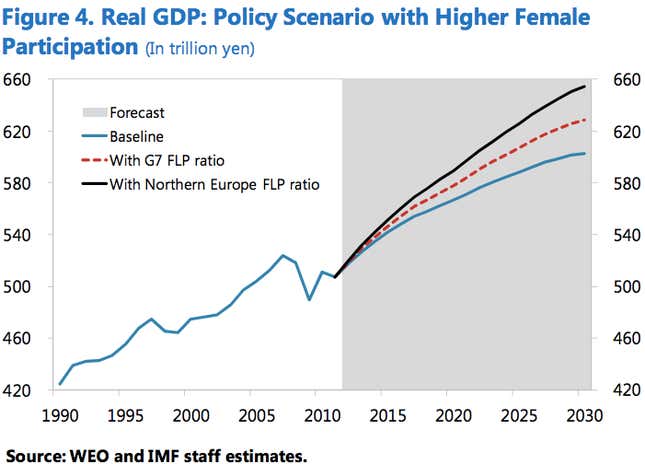

Let’s hope Abe and company have a few more ideas up their sleeves. Making good use of what Goldman Sachs economist Kathy Matsui calls “its most underutilized asset”—the some 8.2 million women who would be employed if the female labor participation rate were equal to that for men (62% vs. 80%)—could add up to 15% to Japan’s GDP. Failing to do so will sink Abenomics.

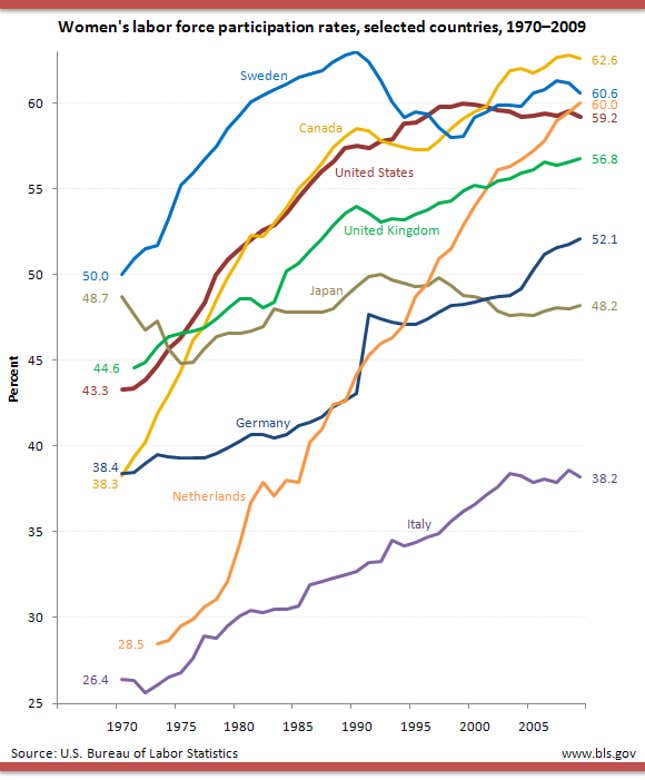

Right now, Japan has one of the lowest female participation rates of developed economies; only one-third of Japanese mothers work.

Meanwhile, Japan desperately needs more workers to offset its elderly overhang, boost productivity and pay more taxes. The workforce might also be more competitive if, say, more than 1.6% of executives at listed Japanese companies were women, as the FT reports. And though women have fewer jobs and earn much less than men, they tend to control the purse strings more than men, and according to Goldman (pdf), their spending has stayed more constant during the downturn. Here’s a look at the IMF projections of how female labor participation could boost GDP (“Northern Europe” female labor participation is around 80%):

Achieving that will require more than policies focused on women alone—the Abe government should also encourage men to spend more time with their families.

For instance, while more—and hopefully, cheaper—daycare will make it easier for women with toddlers to work, it doesn’t help women with older children. They’re still expected to work long hours, the norm in Japanese corporate culture, and one of the chief reasons women cite for staying out of the workforce. And they’re competing with men who feel pressured to be “Japanese workaholics” and to participate in post-work socializing.

The Japanese government recognizes this problem—in 2010 it reformed parental leave laws to guarantee a generous paternity leave (pdf, p.61). But only 2.6% of Japanese men take it. Data aren’t available, but it’s probably safe to assume that rates of care for elderly parents are similarly skewed. And though Japan has employment protections for parents, it doesn’t enforce them enough to guarantee job security, the way Sweden does. Instituting flexible working hours for all employees, as the Netherlands has, would help immensely.

Abe and the LDP currently have a lot of administrative clout. They should use it. Failing to do so promises that Japan’s dwindling supplies of workers and babies will scuttle the benefits of whatever third-arrow reforms they prioritize instead.