For many movies these days, the shortest route to the top of the charts is through the alphabet.

Film studios have figured out that, all else being equal, it’s better for a movie to appear toward the top of the A-to-Z listings where people increasingly pick what they’re going to watch next.

“We call it alpha-stacking,” says Paul Bales of the Asylum, an independent studio that specializes in straight-to-video horror films. Last year, the company generated $16 million in revenue with movies that included Adopting Terror, Air Collision, Alien Origin, American Worships, and Abraham Lincoln vs. Zombies.

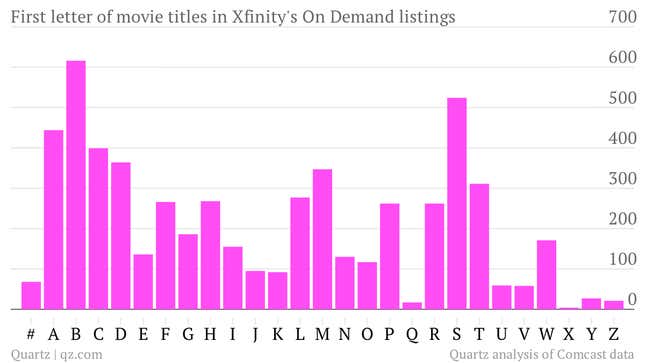

It’s not just the Asylum playing this game. Below is the distribution of video-on-demand movies available from Comcast’s cable television service Xfinity. Some letters, like “A” are commonly used at the start of English words, but the frequency of “B” and “C” are less expected.

Bales is hardly bashful about the practice. “It’s not something we’re doing. It’s a choice the consumer is making,” he reasons. “Americans are lazy people. They can’t be bothered to go past ‘L.'”

His only regret is that, with others catching onto the idea, starting a movie with “A” is no longer enough. In most alphabetical listings, letters are preceded by numbers, and indeed, films produced by the Asylum recently include 100 Below Zero, 13/13/13, and 500 MPH Storm. Bales’s favorite example, released last year, is #holdyourbreath, the hashtag symbol in its first character topping both letters and numbers in video-on-demand (VOD) listings. “It worked,” he says proudly. “It’s one of our best-performing VOD movies.”

(This, by the way, is coming from the same movie studio that produced Sharknado, a made-for-TV thriller about shark-infested tornadoes, which briefly captured the imaginations of Americans earlier this month.)

Playing the alphabet is hardly limited to on-demand movies. Phonebooks are typically front-loaded with small businesses that all seem enamored of the letter “A.” Authors writing under pseudonyms have been known to pick names that appear closer to the start of fiction shelves in bookstores.

But it’s worse for digital media, with seemingly endless supply but few good ways of navigating among the competitors. Companies depend on their products to appear in hand-selected feature menus, crowdsourced most-popular lists, or algorithmic picks. (Netflix recently said that 75% of viewing on the service is driven by its personalized recommendations.) Short of that, it comes down to tricks. People who make mobile apps, for instance, admit to naming conventions they hope will compete alphabetically in crowded app stores.

Alpha-stacking should, in theory, become less effective as more companies do it and better systems for discovering media are developed. Bales thinks the jig may be up soon: ”I’m hearing that there is push-back from the cable companies. I suspect that the push-back is coming from the major studios. Their titles come later in the alphabet. They’re not as shameless as we are.”