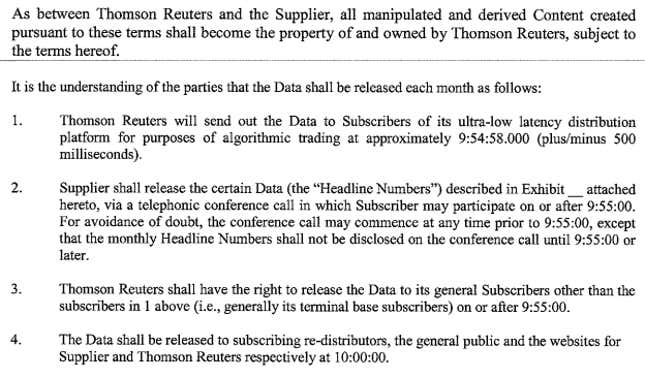

High-speed traders have a distinct advantage in the way Thomson Reuters distributes its University of Michigan Consumer Sentiment Index, a monthly report compiled by Thomson Reuters and the university. In court documents filed last week, the data provider revealed that it distributes data to “‘ultra-low latency’ subscribers” at 9:54:58 AM ET. That’s a full two seconds before most of its subscribers get access to the data at 9:55:00. Non-subscribers are supposed to get access to the data at 10:00:00 AM ET, but the data is widely shared well before then.

Thomson Reuters came under fire last week for a “minor clock synchronization issue” that caused it to release data on the US ISM manufacturing index to high frequency traders 15 milliseconds early. The data leak led to $28 million in trades, according to trading consultancy Nanex, LLC, partly because the data came in particularly weak.

But where last week’s issue seems to have been a mistake, the two-second lead on the consumer data is not. In fact, it’s inked in the deal between Thomson Reuters and the University of Michigan, according to a copy of their contract obtained by Quartz:

The consumer sentiment index is at the center of a lawsuit between Thomson Reuters and Mark Rosenblum, a former employee who sold financial data for the firm. Rosenblum says that while working at Thomson Reuters he spoke to officials at the FBI about the two-tiered data distribution system, because he believed that giving high-frequency traders a head start might violate insider-trading laws. He was fired on August 3, 2012, and in April, he took the company to court for wrongful dismissal.

In its court filing, Thomson Reuters denies that it fired Rosenblum for bringing up these issues. It also denies his allegation that its practice of giving data to high-speed traders two seconds early gave them a trading advantage, though it doesn’t explain how. The suit is ongoing. Thomson Reuters had not responded to requests for comment by press time.

However, there are reasons to suspect that data may have leaked out even earlier than this two-second window. Emails obtained by Quartz show that Thomson Reuters employees who were selling financial information to clients had access to the data well before the official release time—as early as 9:00 a.m. ET, nearly an hour in advance. Rosenblum told Quartz that he believes employees with early access might not always have kept that information to themselves, though he could produce no evidence of it. But a look at trading on the markets backs up that suspicion.

Nanex’s founder, Eric Hunsader, took a closer look at University of Michigan consumer confidence data published on December 7, 2012. If everything went according to plan, he explains, markets should have seen a flurry of activity right around or even slightly after 9:54:58. That’s when algorithms would have kicked in and begun trading on the data.

What he actually sees is activity at 9:54:57.18—nearly a full second before the data was supposed to be released. Moreover, the trading took place in Chicago, which would have received the data about six milliseconds after it was published in New York. Hunsader concludes that the weird, early movement likely happened because someone received the data even earlier than they were supposed to.

“I really believe that this was a case where someone knew this [number] early,” Hunsader said in a phone interview. If you had early information, he reasons, “you wouldn’t want to take a position until really close to the release,” both because you’d want to avoid other adverse market moves ahead of the release and because investors cancel orders prior to a release, making it difficult to find someone to trade with. Hence the trading about a full second before the release. “That tells me that someone was getting as close to the trigger point as possible.”

Hunsader added that this wasn’t the only time he’d seen strange trading activity before the University of Michigan Consumer Sentiment release. In particular, the market has been reacting less violently than it should be at release time. “In the past, we had seen a lot of market reaction at 9:54:58—spectacular market reaction—and we haven’t seen that as much [lately],” he said. If data were going out early by more than a few seconds, “[the reaction] would be buried. Once it goes out even 10 seconds early, we wouldn’t see it at all.”

It’s hardly news that data centers and exchanges give out better information and better trading options to subscribers—and some of their most important subscribers happen to be high-frequency trading firms. But this advantage often comes at the expense of most retail and institutional investors. “I guarantee you none of those people have any idea that a handful of people have access to [University of Michigan Consumer Sentiment] data two seconds earlier,” Rosenblum told Quartz. Legal or no, it’s worth reconsidering whether early data distribution gives the biggest and wealthiest firms an advantage.