India’s population will overtake China’s by 2021, putting a huge strain on resources and public services. And though the country’s overall birth rate has fallen a lot, it’s still explosive in rural areas (pdf).

So how to get rural women to have fewer children? As we just discussed, coercive sterilization is probably not the best way to go. But things you might expect to bring the birth rate down, like higher female literacy or urbanization, don’t necessarily seem to do so, as Stanford professor Martin Lewis explains.

However, there’s one kinda bizarre thing that does correlate with lower fertility: cable TV.

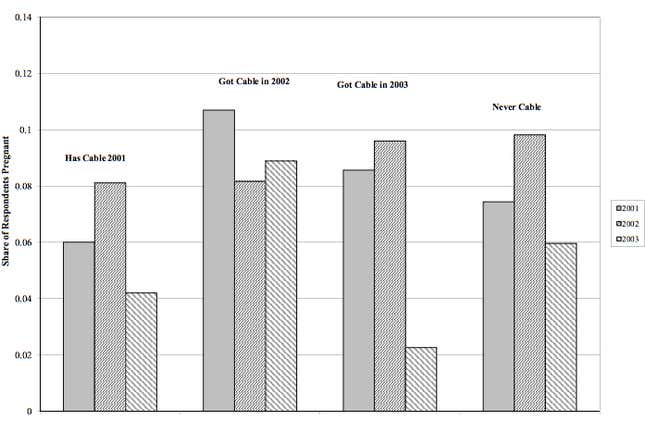

Over a three-year period, academics Robert Jensen and Emily Oster researched rural villages in five Indian states. They found that once the village got cable TV access, fertility declined within a year (pdf):

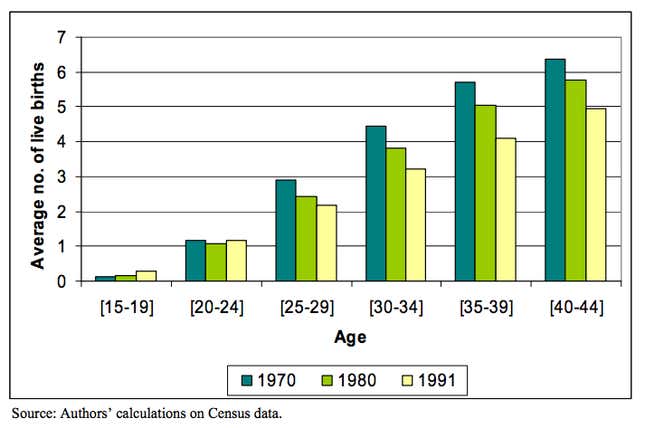

This has happened elsewhere too. Fertility dropped markedly as more and more Brazilian villages got on the cable grid (pdf) from 1970 to 1999, according to research by academics Eliana La Ferrara, Alberto Chong, and Suzanne Duryea. Here’s how birth rates declined in Brazil over the years that cable availability spread:

One thing stands out in that study, though. Fertility only declined among poor rural women who could access Rede Globo, the network with a corner on the telenovela market. Why? Perhaps because, at a time in the 1970s when fertility was running at around 5.8 births per woman, nearly three-quarters of female characters of child-bearing age on Globo’s telenovela shows had no kids and 21% had just one child.

Also notable: When Brazilian women were exposed to imported TV shows, nothing happened. The authors note that “programs that are imported from Mexico and the US…are generally not perceived as realistic portraits of Brazilian society.” This suggested to them that “TV programs that are framed in a way that makes them immediately relevant for people’s everyday life may have significant effects on individual choices.”

Though Jensen and Oster’s research in India didn’t focus on the impact of a single type of program, they too conclude that Indian soap operas, which tend to feature independent urban women, might be the critical factor in driving down birth rates. Exposure to TV also tended to accompany a shift in values—fewer rural women who had TV said they found domestic violence acceptable or expressed a preference for male children.

So perhaps the Indian government should consider ramping up the reach of cable, and churning out Bollywood-style telenovelas with strong, compelling and—most importantly—childless female leads. It’s got to be a lot cheaper than sterilization camps.