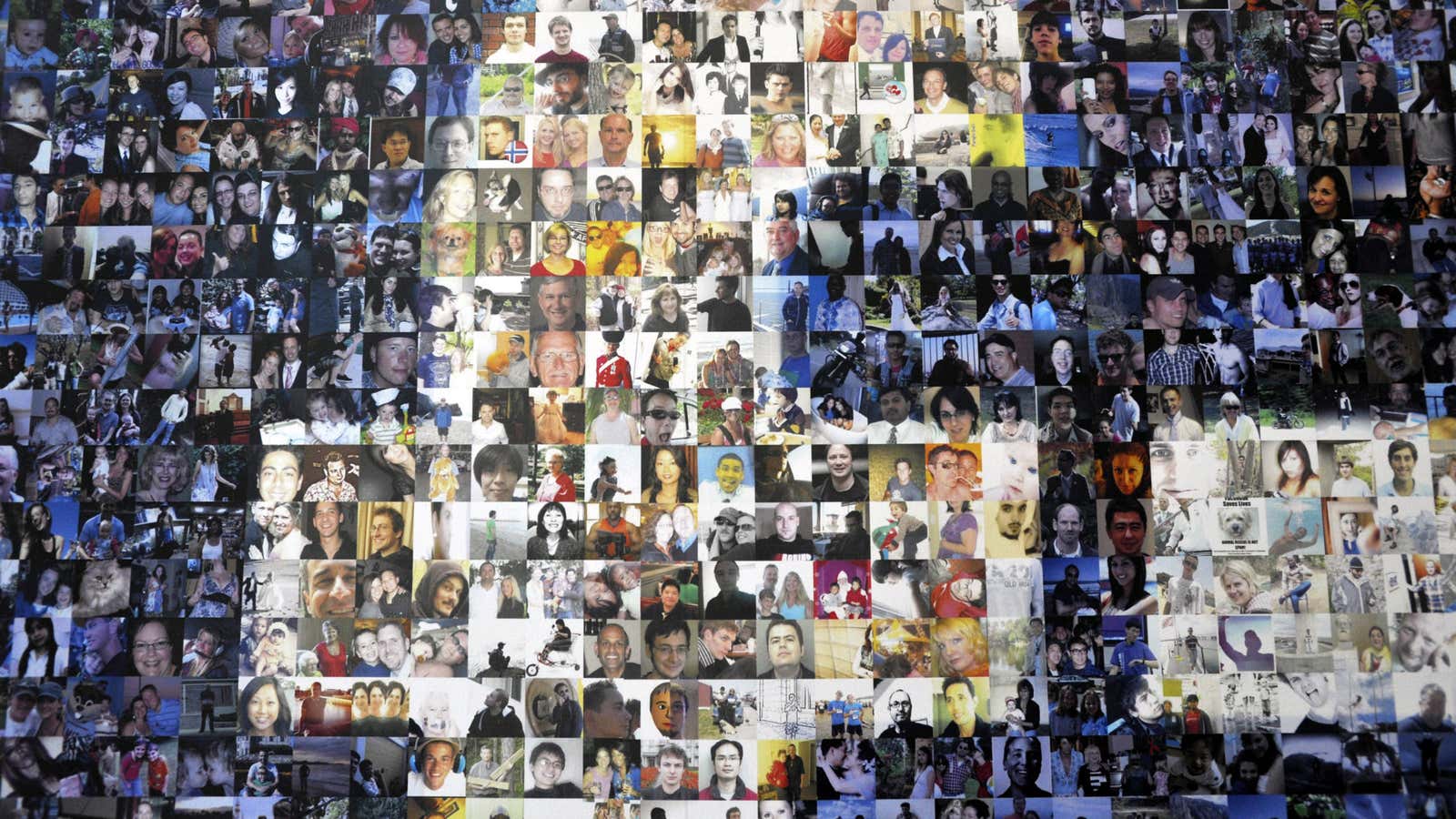

Human beings are notoriously bad at visualizing large numbers. So getting a handle on the sheer size of Facebook’s 1.1 billion users is understandably difficult. Imagine Manhattan’s population density in an area twice the size of the state of New Jersey (a little over 8,700 sq. miles) and you’ll get an idea of Facebook’s sheer scale.

With all of those people sharing untold billions of moments every day, Facebook has faced unremitting scrutiny regarding user privacy—specifically, what is public to whom and the degree to which users control their own data. For the most part, Facebook has done a pretty good job in establishing clear data usage policies that govern what information is private and what information can be used by advertisers without your permission.

The core paradigm is that of opt-in: you control what data you post, how public or private it is, and which 3rd party apps can access it. This is as it should be. But a new service, Lulu, abuses opt-in to such an alarming degree that it’s a wonder Facebook has not already shut it down.

The basic premise is this: A girl meets a guy at a party, but wants to know what other women think of him. She signs into Lulu where, if the lucky man is in her extended Facebook network, she can find anonymous reviews left by other women covering everything from his looks to his earning power to his sexual prowess (or lack thereof).

Lulu’s founder, Alexandra Chong, says that the service is simply the natural extension of women’s longstanding desire to see if a guy is everything he’s purporting to be. And while some may consider that a worthy goal, the site’s methods should draw serious scrutiny from anyone remotely concerned with their digital privacy.

Men, whose Facebook profiles provide the foundational content for the site, are explicitly banned from the app. Furthermore, they are not notified when their information is captured, nor when their profiles are viewed, saved, or reviewed. In fact, the only way a man can have his information removed from the site is to email his Facebook profile name to privacy@onlulu.com or to download a separate app (conveniently also made by Lulu) and then deactivate his own profile.

One doesn’t need to be John Rawls to imagine the public outcry that would meet a service that crawled Facebook for women’s names and profile photos for the explicit purpose of rating them as potential partners—almost solely based on their appearance. Facebook itself started as much less innocuous version of that, and was promptly harangued in the press and shut down. That women have actually taken to defending Lulu is even harder to understand.

That women want to discuss guys they may know in common is hardly surprising. What is surprising is that investors have put more than $3.5 million into a service that furthers that aim by stealing the information of hundreds of millions of people without their knowledge or permission in order to subject them to public scrutiny.

In an age where opt-in is the accepted standard for all social networks, it is horrifying that one exists where the profile owners are banned and the profile reviewers are anonymous. Lulu disgraces not just the women who use it but also the companies that allow it to exist.