On Friday, June 21, the longest day of the year, the Royal Shakespeare Company will launch its latest production of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” It will be no ordinary show. The performance will last three days—from Friday night (midsummer night) through to Sunday, matching the timeline of the script—but most of it won’t be in front of a physical audience.

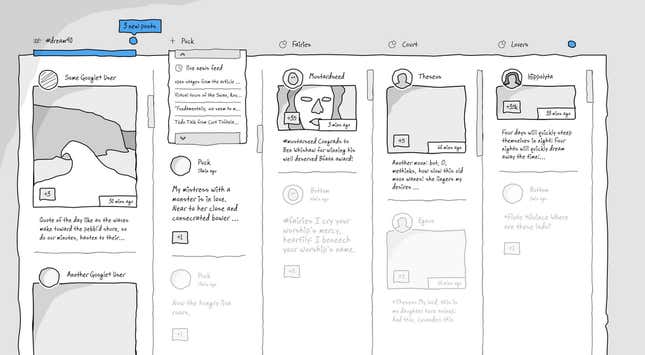

Instead the action will be broadcast on a “virtual stage”, an accretive layer of activity unfolding online as characters important and peripheral blog about what’s going on, post video clips, and interact with each other—and the public—on Google+. The only more-or-less conventional part of the performance will be the wedding scene between Theseus and Hippolyta—and that will take place at a huge party open to the public at the company’s home town of Stratford-upon-Avon.

The idea behind the production, which the RSC has titled “Midsummer Night’s Dreaming,” is to recreate the online chatter that surrounds any event in the real world, such as breaking news or an unfolding scandal, says Geraldine Collinge of the RSC. The experiment is one of a spate of recent efforts to fuse digital technology with the performing arts. The company tried something similar in 2010, when it produced “Such Tweet Sorrow,” a retelling of Romeo and Juliet through Twitter. (It received mixed reviews.)

Opera, often seen as a fusty relic for pensioners and one-percenters, is also embracing new technologies. Michel van der Aa, a Dutch composer, teamed up this spring with the novelist David Mitchell to make “Sunken Garden,” which uses 3D film as an important part of the production. Video projection can be found in everything from modern opera such as Philip Glass’s “Satyagraha” to re-interpretations of classics, such as Terry Gilliam’s mind-bending production of Berlioz’s “The Damnation of Faust.”

Technology has long been used to make live theater and opera reach more people. It started with the recording and broadcasting of performances on TV and radio. The internet opened up new possibilities: On December 30, 2006, New York’s Metropolitan Opera live-streamed Mozart’s “The Magic Flute” in high definition to cinemas across the world, and its productions now reach 60 countries this way. Britain’s National Theatre took up a similar approach with NT Live, which allows many thousands of people to watch a single evening’s work.

Now, though, technology is being used not just to broaden the audience, but to create depth in the production. Putting a 3D film in an opera might be thought of as gratuitous, and the very idea of Oberon, Titania and Puck trading quips on Google+ may seem perfectly ghastly, but the reasoning is sound. “Culture should hold a mirror up to society,” says Tom Uglow from Google, which is working alongside the RSC for Midsummer Night’s Dream. “So if you’re a contemporary mirror, you should use contemporary tools to do this.”

Through the glass, down the hole

“We all grew up with technology—it’s so much part of our daily lives,” says Michel van der Aa, who composed and directed “Sunken Garden”. “I don’t see it as an extra layer but I find it a very organic thing to embed in my work.” Van der Aa has been mixing digital technology into his productions for much of his career. His 2006 opera “After Life” combined film projection interacting with live artists, a trick he repeated in different form with ”Up Close,” a 2010 cello concerto.

His latest work, “Sunken Garden,” is about a place between heaven and earth. It also relies on mixing live opera singers with recordings, but at scale: the entire backdrop turns into a giant screen showing a 3D film of the eponymous garden and its inhabitants. With 3D glasses on, it is easy to forget that half the characters aren’t actually in the hall.

Perhaps less obvious as a tool for adding richness to a production, but no less ambitious, is video projection, which has become increasingly common over the past few years. A particularly impressive example is “Dr. Dee,” created by director Rufus Norris and the musician Damon Albarn, which ran at the English National Opera last year. Telling the story of an Elizabethan scientist and mathematician (and also a bit of a loon), “Dr. Dee” used elaborate video projections to communicate the visions and calculations of Dee’s mind. The projection received as much acclaim as the rest of the opera.

It was well deserved. The projection, designed by Lysander Ashton, was a character in its own right and involved a tremendous amount of work to get right. “At the heart of it is a media server, which is a computer that does a lot of graphic compositing live,” says Ashton. “We break the artwork down into multiple layers that can be laid up in real time each time a show is done.” At the other end of the hall, Ashton responded to what was happening on stage, controlling two projectors that beamed video on moving targets like sheets of cloth flying across stage.

Ashton is a part of 59 Productions, a film and new media production house in London that, among many other projects, did “Dr. Dee” and has worked on video in ballet, theatre and operas like “Satyagraha” and Nico Muhly’s “Two Boys” (itself a story about internet friendships), as well as the supersize projections in the London Olympics opening ceremony.

Making it disappear

59 Productions uses a lot of different media in its projections—video, text, animation—and getting it all right takes a lot of computing power. Yet Ashton says his ambition is to make the technology responsible for his work disappear.

According to Andrew Dickson, theater editor at The Guardian, ”Digital projection is just one tool that theater directors can use, just as they would use a lighting box. It is almost part of the furniture.” That suggests Ashton may be succeeding in his goal. The relative novelty of social networks and 3D film, at least in theater, means they face bigger hurdles before they can become commonplace. But the same could probably have said of masques when Shakespeare started including them in his plays, says the RSC’s Collinge, because it challenged the way people thought and gave the actors new ways to express themselves.

Technology pervades the arts. From moving sets to mechanized lighting, a modern production has dozens of tools at its disposal that Shakespeare could only have dreamed of. Yet we barely notice most of them. The ideal result for experiments like the RSC’s or productions like van der Aa’s would be if we stopped noticing the technology there too.