One day we won’t need technology, because we’ll be the technology.

At least that’s the promise of tech leaders like Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg, and Regina Dugan, who have all expressed interest (and Musk even started a company) around the idea of merging our brains with computers. At Facebook’s F8 developer conference, Zuckerberg said this will undoubtedly be the future, and Regina Dugan, head of Facebook’s secretive Building 8 research lab spoke at length about the company’s pursuits.

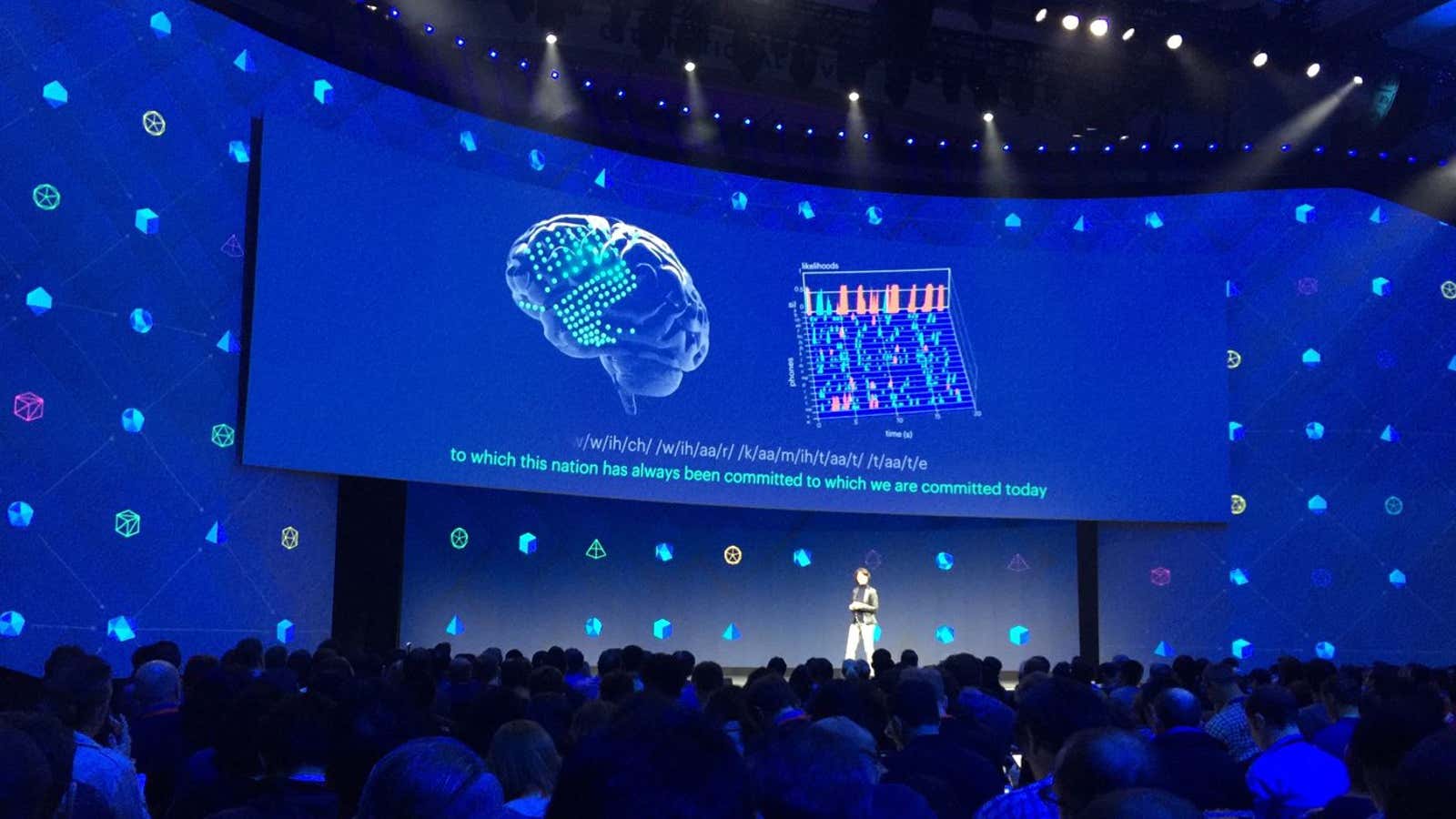

“You have many thoughts, you choose to share some of them. We’re talking about decoding those words, the ones you’ve chosen to share,” Dugan told an F8 audience. “The ability to send a quick text without taking out your phone, or respond to an email without leaving the party.”

Such technology as we know it today, referred to as “neural lace,” has been described by early researchers as a fine mesh that could be injected into our brains so our electric thoughts can be easily translated into machine-readable bytes. While neural lace has been an area of research for decades, what Musk envisions as a recreational device is still many years away.

Preliminary research, like the neural lace published in Nature Nanotechnology (pdf) in June 2015, has focused on the mechanism of injecting such a device into a mouse’s brain. The neural lace can actually function after being injected. But “functioning” is somewhat deceptive, because we don’t necessarily understand the signals coming from a mouse’s brain, and certainly can’t decode the rodent’s thought. Neural lace is more a marvel of material design than neuroscience, according to the paper’s lead author. (And by the way, we shouldn’t trust mice to accurately mimic humans.)

“At the outset no one, and a lot of reviewers of that first paper, believed we could even inject electronics through a needle and then not destroy the electronics. A lot of it was actually not related to anything biological. It was really about the materials science, and also showing that you could literally inject this into other kinds of structures,” Charles Leiber, a Harvard researcher leading the study, told Nautilus.

The scientific adviser for another neural lace company, Kernel, told Wired that the idea was a “non-starter” as a recreational device in any foreseeable medical climate, due to the inherent risk of neurosurgery.

“Neurosurgeons are completely reluctant to do any surgery that is not a required surgery because the person has a disease state,” said David Eagleman, Stanford neuroscientist and Kernel adviser. “The implanting of electrodes idea is doomed from the start.”

However, limited medical tests for those who have lost their ability to communicate have had success. For instance, after a brain implant, a woman suffering from Lou Gehrig’s is able to move a cursor around a screen fast enough to type eight words per minute, according to IEEE Spectrum.

Dugan has a more realistic approach for a consumer product. Methods which require surgery aren’t reasonable and “don’t scale,” she said. ”No such technology exists today,” she said on stage, further noting that the company will have to invent a new mechanism for decoding thought. She detailed a bit of research the company has explored that uses a myriad of light and blood-oxygen sensors. Facebook hopes this undefined technology will enable humans to type 100 words a minute by simply thinking.

Dugan had spoken about different ways to bridge humans and technology when she was head of Google’s Advanced Technology and Projects. Then, the idea was easier to deploy—a wearable “tattoo” that could interact with a person’s smartphone. ”Electronics are boxy and rigid, and humans are curvy and soft,” Dugan said at a 2013 AllThingsD conference. “That’s a mechanical mismatch.”

Facebook is apparently stocking up on talent to bypass that mismatch—on stage at F8, Dugan said Facebook has 60 engineers working on the problem. TechCrunch reported that the company is hiring a Brain-Computer Interface Engineer and a Neural Imaging Engineer. The job postings describe a two-year project within Building 8 that focuses on a “non-invasive” brain-computer interface. In interview with MIT Technology Review, Dugan said that two years should be enough time to tell whether it’s viable to build neural interfaces into a consumer product.

But consider this: Those leading Silicon Valley think they can master an computer’s interaction with the human brain, but the companies they lead can’t yet master virtual reality without people getting sick, nor can they build an augmented reality headset, or code safe self-driving cars.

So let’s hold the applause for now.