A bloated agricultural subsidy bill in the United States is aimed at Iowa and California, but will have repercussions everywhere from Brazil to Geneva.

Agribusiness versus the poor

In the US, the big debate is how much spending to cut in a time of debt anxiety, and where: the food stamps program that subsidizes nutrition for the poor, about 80% of the nearly trillion-dollar bill, or subsidies to farmers at a time of high commodity prices. In the House version of the bill, food stamps are facing serious cuts, with conservatives alleging fraud and over-generosity, but farm subsidies, though their delivery mechanism will change, face only moderate cuts. Ironically, the latter program has the bigger fraud problem.

In a surprise, that bill failed to pass the House of Representatives today as Democrats refused to support deep cuts to food stamps—which make for excellent economic stimulus—and Republicans hung their leadership out to dry because the bill didn’t cut enough. The fact that a bipartisan version passed the Senate, and the unrelenting pressure of agribusiness like Archer Daniels Midland and Cargill eager to see more certainty in agriculture policy, make it likely that a version will soon become law.

Developing economies still dinged

Farmers are richer than the average American, and US lawmakers want to stop giving money directly to farmers when prices fall, which is called direct support. While the farm bill cuts these programs, it makes up for them by increasing the generosity of already-generous crop insurance programs, including a plan to insure the deductibles on the insurance.

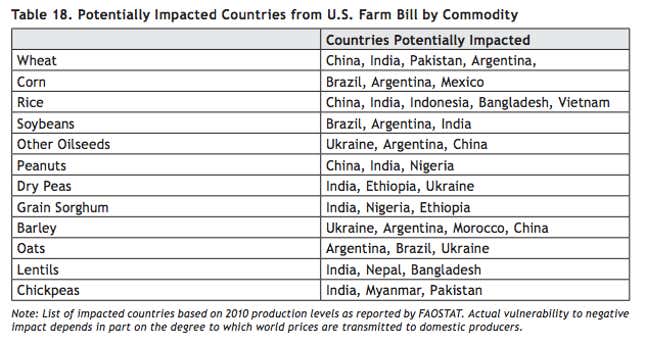

While the end of direct subsidies is seen as a step away from market distortion and more in-line with international trade rules, advocates for sustainable agriculture fear the new approach will lead farmers to switch to crops that put them in direct, subsidized competition with developing nations. The bill contains boosters for everything from sushi rice to catfish, not to mention milk. If prices start to fall, that means trouble for all kinds of countries, including Brazil, India, Mali, and Pakistan:

Too sweet a deal

Protection for sugar, in particular, will irritate Brazil, which would love to sell its far-cheaper sugar in the US. Companies that use sugar to make food and candy say that consumers are spending $3.5 billion more than they have to because of the lack of competition. Sugar producers say they need the protection to compete with global suppliers, but it seems clear that the way farm bill’s approach is creating an over-supply: The US will spend $100 million in 2013 buying excess sugar and selling it at a loss to ethanol manufacturers.

Trade deals turn on agricultural subsidies

Economists don’t like to see any industry subsidized, and agriculture is no exception. Subsidies distort markets and make it harder for developing economies to advance. Disagreements about state support for farmers has gotten the US in trouble with the World Trade Organization, and advanced economy ag subsidies are perhaps the single largest divide keeping the Doha Round of global trade talks stalled. They are also a hurdle before a potential US-EU free trade agreement. While this bill makes technical changes to move closer to world standards, it still represents a divisive amount of state support.

Adding aid insult to injury

Another failure in the bill was a plan to reform US food aid. President Obama had hoped to change a policy that insisted any food supplies sent to countries facing disaster or famine must come from the United States and be transported by US ships. This is obviously slower and less efficient than simply purchasing nearby food and transporting it to the affected area, and also denies the local region the economic benefits of the aid money. However, amendments that would change the policy did not pass.