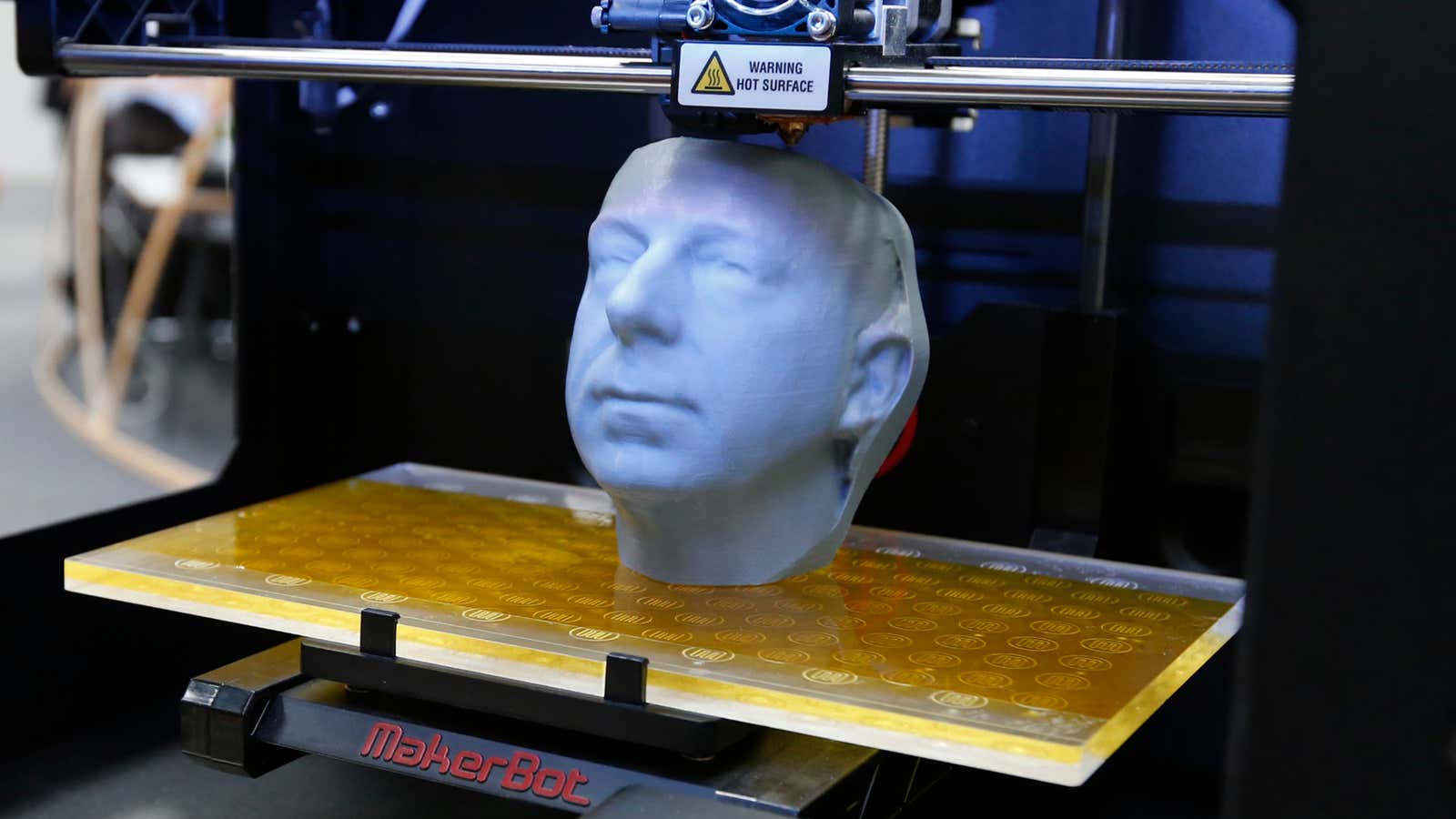

In his living room in San Diego right now, Cosmo Wenman has two life-sized reproductions of the British Museum’s Head of a Horse of Selene, a magnificently life-like sculpture with nostrils flared that dates to around 432 B.C. The original in Britain is made of marble, about three feet end-to-end. Wenman’s copies, created with an older digital camera and a MakerBot 3D printer, are clearly reproductions as soon as you lift them up. Created out of plastic, coated in a bronze patina, they weigh about 8 pounds each.

For the last year or so, Wenman has been casing some of the world’s great sculptures for at-home replication, photographing them from every angle in plain sight inside the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, the Louvre in Paris, the Tate Britain, the British Museum and a few others.

“I’ve gotten some hairy eyeballs from some guards who think I look like just a really enthusiastic photographer,” says Wenman, who describes himself as an informal art student all his life. He snaps maybe 200 images for each piece. That’s more than he needs to construct the 3D files in an Autodesk program. But he figures the software will keep improving, and when that happens, he wants to be ready with as many images as possible. This all looks, as you can imagine, a little strange.

“They’ve thought I might be taking pictures of the museum itself,” he says of the security guards. “Like ‘why are you taking pictures of our lighting and security cameras? Why are you taking pictures of the way the painting is mounted on the wall?’ And I tell them I’m just taking pictures of the object, I’m not prepping for a heist.”

Wenman’s plan is to make all of his 3D files publicly available in the MakerBot Thingiverse, where anyone could freely recreate sculptures that are currently accessible only in art museums. This is understandably an idea art museums might not love. Then again, Wenman is currently drumming up money on Kickstarter to travel to Switzerland, where he’s actually been invited to do this by the The Skulpturhalle Basel Museum.

Wenman’s own Head of a Horse of Selene. Courtesy of Cosmo Wenman.

Art museums have been scanning pieces like this for archival purposes for years. What’s new is that just about anyone can now walk into a gallery—assuming that photography is allowed—and do this, too. “To me,” Wenman says, “it seems very analogous to the potential behind the Napster-like free-for-all of unauthorized reproduction and sharing and remixing of music.”

Schoolchildren, he suggests, could reproduce their own art instead of flipping the pages in a text book. Artists could use the 3D designs to create modern sculpture inspired by famous antiquities, in much the same way that musicians sample each other. Smaller local museums, in particular, might use this as a way of drawing attention to little-known collections. And, of course, any 3D printing amateur could download these files to experience art that lives thousands of miles away.

Many major art museums around the world have already begun to post online for public viewing high-resolution digital images of their collections. “We’re a public institution,” the director of collections at the Rijksmuseum recently told the New York Times, ”and so the art and objects we have are, in a way, everyone’s property.”

The prospect of 3D printing, however, takes this sentiment literally. Imagine if art museums became the place you went to see… originals. Or, imagine bypassing the giftshop because you could make your own Rodin at home.

Wenman is sticking to antiquities to avoid any copyright concern. Art created during most of the 20th century is protected under copyright for the life of the artist, plus the next 70 years. It’s easy to imagine those pieces tucked into the “no-photography” room in a future full of digital cameras and amateur 3D printers. Wenman says he isn’t wringing his hands over the possibility of counterfeit art (it’s quite possible, though, to use these 3D-printed plastic sculptures to model more realistic bronze reproductions).

Critics have raised similar objections, Wenman says, upon the arrival of all kinds of other technology, including the printing press (people will republish original manuscripts!). “Those are the most unimaginative objections you could possibly hope to throw at a new technology,” he says.

He’s more interested in what else people could create with these 3D files, not whether they’ll create cheap knock-offs. And the stakes for museums are much more interesting than simply whether or not copy-cats get to reproduce their goods.

“The way that music today is just completely informed by previous generation’s music, that’s all happening because of low-cost digital music transfer and storage and editing,” he says. “If there’s a possibility for there to be something analogous, a new form of art, a new sort of energy level in sculptural art, that is very interesting to me.”

Hat tip VSL.

Emily Badger is a staff writer at The Atlantic Cities. Her work has previously appeared in Pacific Standard, GOOD, The Christian Science Monitor, and The New York Times. She lives in the Washington, D.C. area.

This originally appeared at The Atlantic Cities. More on our sister site:

Get ready to use your ipad for the full flight

America’s landlord’s are far less likely to rent to gay couples