As China’s richest man, Zong Qinghou probably knows a thing or two about wealth. Poverty, however…

“We don’t need to solve the problem of the rich-poor gap,” said Zong Qinghou, the founder of the massive beverage company Wahaha, at a launch for a chain of luxury shopping malls. “We need to solve the problem of common prosperity.”

Zong was presumably referring to the new administration’s plan to address income inequality. He has professed even more extreme views in the past: ”I believe wealth should be in the hands of those who know how to create more wealth,” said Zong in an interview last year (paywall).

According to Bloomberg’s estimate, Zong is worth $11.3 billion.

Oddly enough, Zong’s wealth is actually self-made. Born into penury in Jiangsu province in 1945, Zong began making his fortune by selling popsicles and stationery from a Hangzhou grocery stand in 1987. His launch of Wahaha Oral Liquid, an appetite stimulant for children, propelled his company to national success.

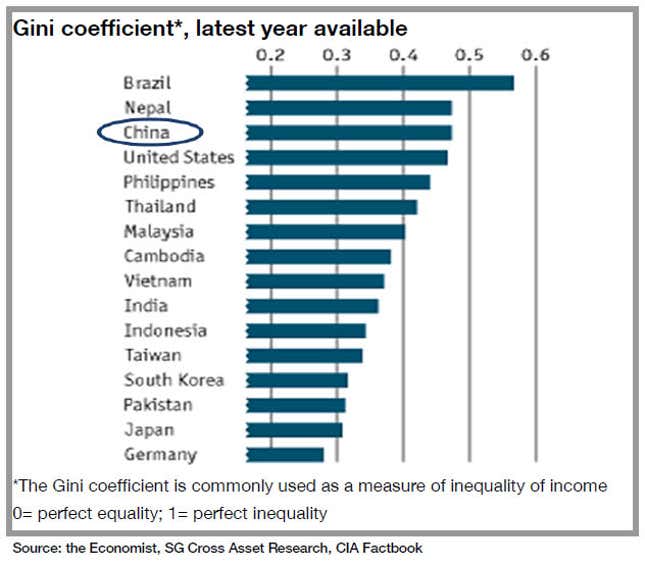

So Zong probably knows a lot more about the other side of the wealth gap than most of China’s business elite. That’s why it’s galling that he’s dismissing the real frutrations of China’s working classes. A glance around any major city reveals that China has no shortage of enormous wealth. But it isn’t being distributed equitably—in fact, the gap is widening. That’s a source of rising public discontent. Here’s a look at that:

And despite Zong’s “trickle-down” views, investment isn’t exactly scarce at the moment. The problem has more to do with the fact that, whether through the government apparatus or informal networks, the Chinese Communist Party control that wealth.

Zong disputes this, arguing that a mere “minority” of China’s affluent (paywall) made their fortunes by bribing government officials.

This defense is odd considering that Zong and Wahaha have benefited from party connections. Until recently, Wahaha was owned by the Hangzhou city government and enjoyed incentives and subsidies under that aegis. This arrangement allowed it to avoid trademark obligations (pdf) in its joint venture with Danone, which has since dissolved.

Zong is also quite snuggly with the Party. A delegate to the National People’s Congress, the country’s highest legislative body, he represents Zhejiang province, where president Xi Jinping served as the Party’s provincial head from 2002 to 2007.

And Wahaha’s obligatory Party zeal may have helped Zong quash coverage when three girls died allegedly from drinking a Wahaha tonic in the 1990s, as Quartz contributor James McGregor’s One Billion Customers details. After a Beijing newspaper broke the story, Zong’s sway with the Propaganda Department resulted in the newspaper’s president’s firing (paywall).

Of course, Zong is generally right that “prosperity” isn’t exactly “common” in China right now, and that promoting private enterprise is vital. (And his latest remarks are a disappointing departure from previous ones criticizing the state-led economy.) But his obliviousness hits at the core of the rich-poor gap—that the prerequisite for getting rich is becoming part of the state.