China swears it’s kicking that nasty credit addiction. So why’d it fall off the wagon in Q2?

The 7.5% GDP growth China reported on Monday was no surprise. Roughly in line with the government’s target growth rate for 7.5% in 2013, it was also consistent with the government’s message of late that it would prioritize structural reform over growth.

The 7.5% GDP growth China reported on Monday was no surprise. Roughly in line with the government’s target growth rate for 7.5% in 2013, it was also consistent with the government’s message of late that it would prioritize structural reform over growth.

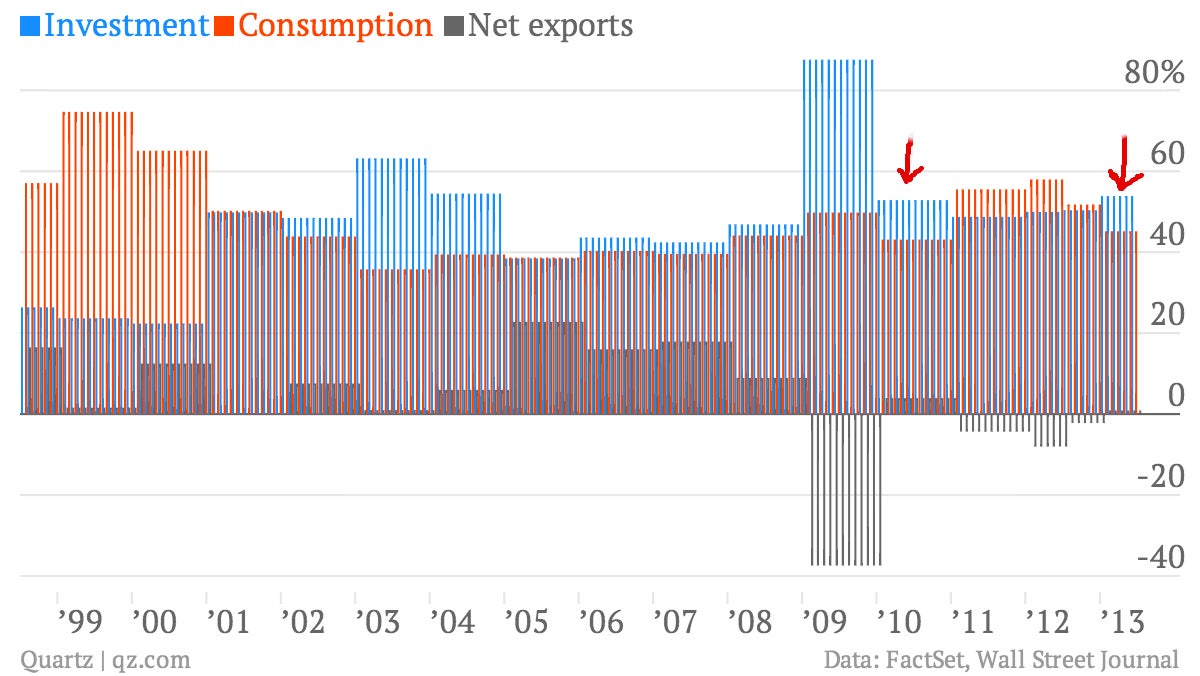

Not that there weren’t any surprises in the Q2 data. As it happens, the composition of China’s economic output showed something quite unexpected. Make that “alarming,” actually. Consumption contributed only 45.2% of GDP in H1 2013, down from 60.4% in H1 2012 (paywall). Meanwhile, investment’s share leapt to the highest levels we’ve seen since 2009.

Put another way, in Q2, China basically reverted to the same economic structure it had in 2010, when Beijing was pumping trillions of dollars worth of stimulus lending into the economy. Here’s a look at that—and recall that this doesn’t even count the estimated $2 trillion in off-balance-sheet lending:

As everyone should know by now, the Chinese government needs to “rebalance” the economy. The goal is to move toward a sustainable economy and away from the current model, which effectively taxes households in order to provide cheap credit to businesses. The problem is that this shift is hard. If it pulls back dramatically on lending, growth will implode. In fact, June gave us a foretaste of the financial bedlam that would cause, when a liquidity shortage caused banks to default on each others loans and generally be unwilling to lend to each other.

But not only would the financial sector go into tailspin, but hundreds of businesses will fold. Those that stay afloat will stop hiring or slash headcount. Consumers will understandably freak out. And they most certainly won’t start spending the way the economy needs them to.

The government can’t do that. Instead it must gradually slow credit growth while simultaneously spurring consumption.

In Q2, neither of these things happened.

The questions remains: was Q2’s shuffle of investment and consumption a fluke? Or does it mark a return to the heady lend-o-rama days of 2010?

The biggest argument in favor of the “fluke” theory is that China’s official data is notoriously unreliable. In addition, consumption of services is hard to track. Since it usually takes longer to amass that data, its contribution might not be fully accounted for in the Q2 data.

The points in favor of “not a fluke,” however, should not be ignored. First we have steadily rising loan growth. Also, retail sales during H1 grew only 12.7% on the previous year (link in Chinese), after expanding 14.4% in H1 of 2012. Plus, the growth in per capita income (link in Chinese) of urban residents slowed in the first half. At 6.5%, wages are now growing more sluggishly than China’s economy, which will stifle consumption even more.

It’ll take a few more quarters to see what’s really going on. But if Q2 really was a backslide to the 2010 growth model, “rebalancing” will be even more drawn-out and excruciating than anyone expected.