China gross domestic product grew 7.5% in the second quarter—a more-than-healthy rate for most countries but one that qualifies as a struggle for the policymakers in Beijing, as they attempt to reform the world’s second-largest economy with a minimum of short-term pain.

Overall GDP growth for the first half came in at 7.6%. Recall that 7.7% Q1 growth came as an unpleasant surprise when it was published in April. Today’s announcement was a much different story: Chinese leaders have been telling financial markets to expect a slowdown, most notably when finance minister Lou Jiwei remarked last week that growth of only 6.5% would be acceptable. (The state-owned Xinhua news agency confused matters slightly by “correcting” his remarks the following day.)

Even without Lou’s remarks, last week’s surprisingly weak trade data made it pretty clear that the export engine of growth was truly sputtering.

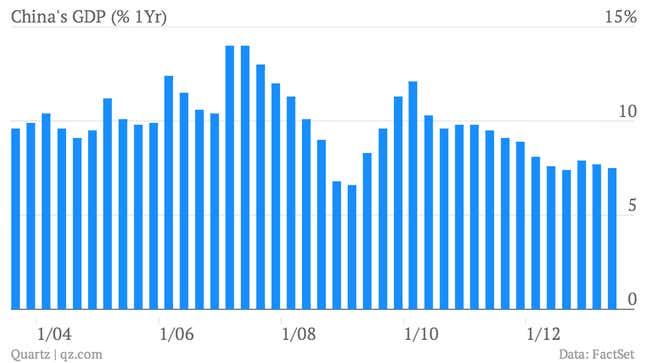

Do the GDP figures mean that Beijing has everything under control? Sort of. However, data also out today on fixed-asset investment and industrial production show that the government is not exactly switching off the investment-led growth model. First, here’s a look at the GDP trend:

So where is that growth coming from? For a start, fixed-asset investment rose 20.1% in the first half of the year (link in Chinese), compared with H1 2012:

What we’re seeing here is that investment in infrastructure and property is slowing down—but not that much.

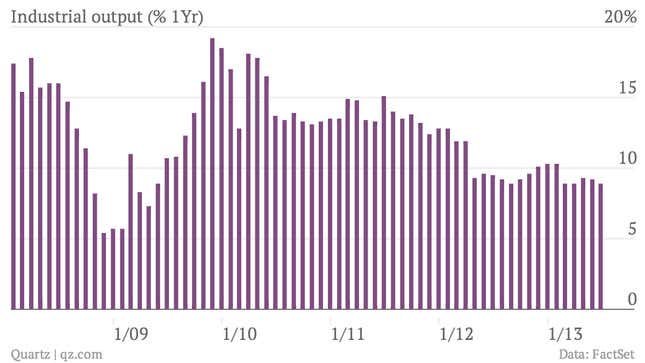

Meanwhile, industrial output, which was up 8.9% in June (link in Chinese), follows a similar pattern:

What does all this mean? Economic output is slowing as demand continues to ebb and as overcapacity burdens a rising number of sectors.

And despite Beijing’s attempts to rebalance growth, investment in infrastructure and property development investment is still clearly powering the economy. For instance, investment in real estate development rose 20.3% in the first half of 2013 (link in Chinese), versus H2 2012. And factories continue to churn out cement, glass and metals at rates faster than overall production (with the exception of steel, probably due to the current glut).

This might seem odd given that lending continues to surge. But as we’ve discussed, businesses and local governments are increasingly taking out new loans to pay off old ones—and that’s money that isn’t being sunk into new condos, overpasses and steel factories.

At the same time, consumer spending isn’t growing as much as Chinese policymakers would like. Retail sales of consumer goods grew only 12.7% year-on-year—1.7 percentage points lower than H1 2012’s growth. The slight good news is that consumption may have started to pick up more recently. June retail sales surged 13.3% on the same period last year, a good deal higher than the total for the first half.

The new administration is prioritizing structural reform in order to shift away from a reliance on investment-driven growth, and toward an economy powered by consumption. The 7.5% Q2 growth is an expected step in that direction, and a gradual enough comedown that it shouldn’t freak out markets too much. But unfortunately, there are no signs in today’s data that reform will be anything but painful.