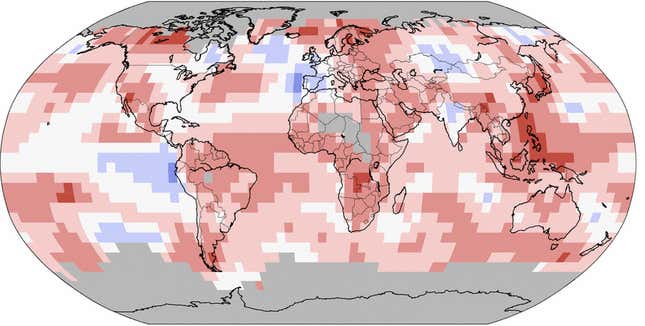

If you were born after February 1985, you’ve never lived through a month of below average global temperatures. According to new data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, in June the earth’s surface was warmer than the 20th century average for the month for the 340th time in a row. It was the fifth hottest June since 1918, NOAA said. (An analysis from NASA says the month was the second hottest since 1880.)

An entire generation has grown up during this streak of hot weather, which Philip Bump, who now writes for the Atlantic Wire, pointed out in the online environmental magazine Grist last year. The last time the global average of land and ocean temperatures was below long-term levels was in February 1985. The United Nations reported earlier in July that more countries have seen record-breaking temperatures in the first decade of this century than ever before. This month, northern Canada, northwestern Russia, southern Japan, the Philippines, southwestern China, and central-southern Africa all saw unprecedented temperatures for the month, according to NOAA.

Still, it wasn’t hot everywhere. Spain saw its coolest June sine 1997. Temperatures in the UK were also lower, about 0.2 degrees celsius (0.4 degrees fahrenheit) below than the long-term average for the month. (A slew of retailers, including spanish clothing company Inditex, said rainy and cool summer weather in Europe was to blame for slower sales for the quarter.)

We’ve already seen some of the effects of a warmer world. Since the early 20th century, the average world temperature has risen by about 0.8 degrees celsius, or 1.4 degrees fahrenheit. Researchers have recorded higher rates of hospitalization and crime. Thanks to melting ice caps in the Arctic, shipping has quadrupled just in the the last year. And last year, warmer temperatures and higher sea levels arguably turned a hurricane that hit the eastern US into a “frankenstorm.”

The United Nations has warned that the average temperature could increase by 4 degrees celsius above pre-industrial levels by 2100, which some researchers say will wreak further havoc, causing extreme temperatures, lower crop yields, damage to ocean ecosystems and human health risks.