The economists and accountants who keep tabs on the US economy have unveiled their latest big project: A massive revision of the US national balance-sheet to include a smarter accounting of investment in creative endeavors ranging from pharmaceutical research and software development to Hollywood films and literary blockbusters.

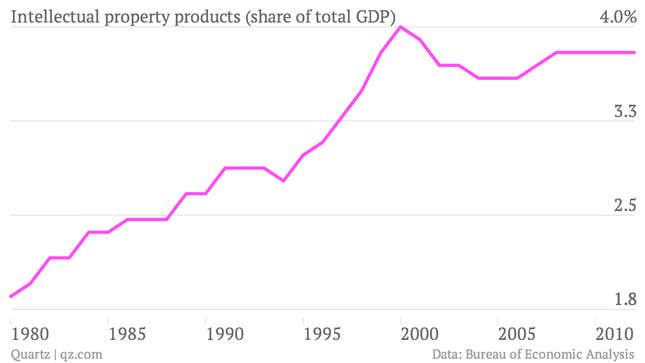

The newly revealed numbers tell a troubling story: Investment in intellectual property peaked at 4% of the total economy in 2000 and has been hovering below that ceiling ever since. And investments in research, development, and other intellectual property has contributed less to US economic growth over the last decade than it did in the eighties or nineties.

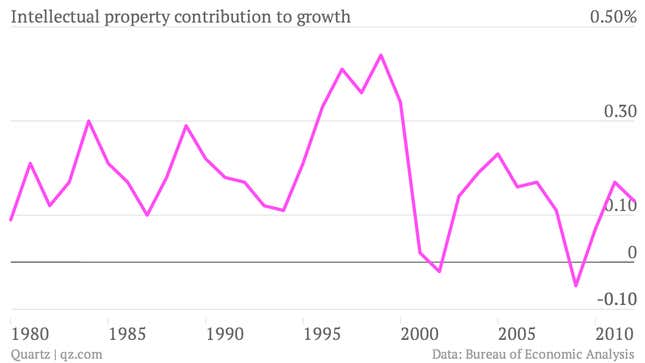

Check out this first chart, which shows how many percentage points investments in IP have contributed to growth. For example, in 2012, the economy expanded by 2.8%, and .13 percentage points of that expansion were from investments in IP:

What you notice is that IP investments played a fairly important role in growth, especially in the middle of the nineties, and plummeted precipitously thereafter. Clearly some of this reflects the tech bubble and the recession, but even at the peak of the housing bubble, when the economy was humming and businesses and people might be expected to invest more, they actually invested less.

You can argue that this fits into the Great Stagnation theory of our economic woes—productivity-enhancing innovations just aren’t coming along like they used to. On the other hand, it might be that society hasn’t run out of ways innovate, but that the US isn’t investing in much in innovation as it should be.

Why is that? One reason is that overall business investment today is inexplicably low. Another is US IP going overseas; while the accounting is supposed to catch that spending in the balance of payments, companies often game those transfer prices for their own tax benefit. It’s also possible that the calculation reflects the changing entertainment marketplace—you make less money on an original song today than you did in 1990. Or it could the pharmaceutical industry, a major R&D spender that so far this century has failed to replicate past success finding blockbuster drugs.

Whatever the reason for the slow growth in intellectual property investment, the new data certainly raises questions about the United States’ vaunted transition to an information economy that maintains its prosperity through knowledge superiority. According to the newly revealed GDP numbers, those glory days are already a decade or more behind us.