America’s most important industry is the best at keeping profits abroad

The bond rating agency Moody’s said yesterday that US companies held $1.45 trillion in cash at the end of 2012, 10% above 2011’s record high.

The bond rating agency Moody’s said yesterday that US companies held $1.45 trillion in cash at the end of 2012, 10% above 2011’s record high.

There are a lot of reasons US companies would hold on to so much cash—general prudence, concerns about the economy or demand for their products, preparations for acquisitions, the growing disadvantage of labor versus capital.

But the growing percentage kept offshore is interesting. Moody’s says $700 billion, or 58% of total US corporate cash, is overseas—at least for tax purposes. (Much of the money corporations keep in their overseas subsidiaries is actually deposited in US financial institutions.)

“The amount overseas reflects the relative strength of most emerging market economies over the last few years, the negative tax consequences of permanently repatriating money to the US, and the domestic use of cash for dividends, share buybacks, and the majority of acquisitions,” Richard Lane, a Moody’s vice president, wrote in the report.

In this case, the most interesting factor is the tax consequences, since non-financial companies report more of their foreign income from tax havens than major trading partners. Companies hang on to profits—and therefore cash—overseas to avoid paying US taxes on them. The US hypothetically taxes worldwide income but in effect lets companies defer payments on foreign income indefinitely. This leads corporations to pay less in taxes while earning record profits, and stacking up record cash abroad.

Technology in general has the largest cash hoard of any sector, with $556 billion, or 38% of the total. The top five companies with the most cash are Apple, Microsoft, Google, Pfizer and Cisco, making up 24% of the total. They keep a larger portion overseas, since the report notes that the top 50 corporations with the most cash keep 63% of their hoard overseas.

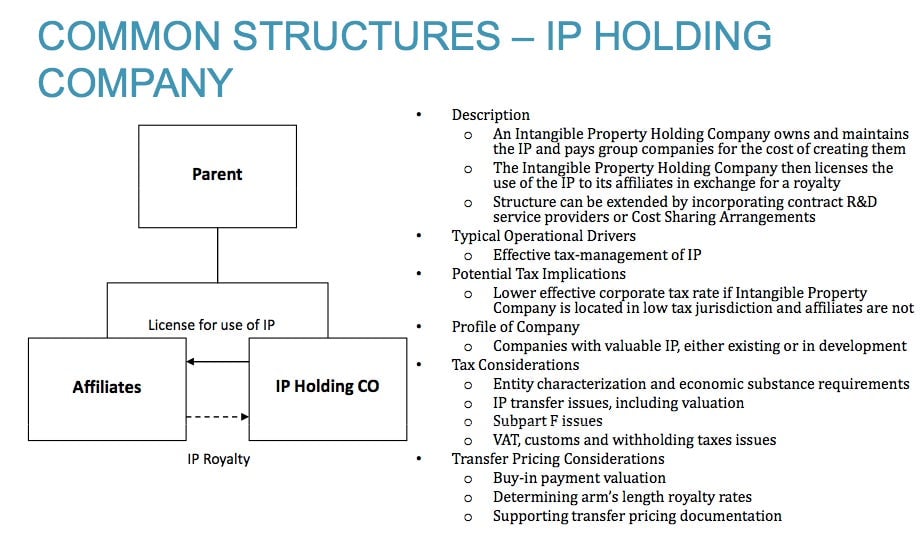

Why are so many technology companies on top of the list? The answer is intellectual property, the end result of most technology endeavors. This is also a factor for drug-maker Pfizer, the only non-tech firm among the top five. Because intellectual property is intangible, it is much easier to move it—and any profits associated with it—overseas for tax purposes. Here’s an example from a presentation by Moss Adams, a Seattle-based accounting and consulting firm:

Which is to say, a company could take the intellectual property behind its digital products (or drugs) and sell it to a subsidiary in a country with a low tax rate, like Bermuda or Ireland. Then, sales to the company’s affiliates in high-tax countries involve a royalty charge for use of the IP—leaving the company’s profits in the tax haven and the affiliates with a tax-deductible expense. You might have heard of “double Irish with a Dutch sandwich,” a complicated version of this basic idea involving multiple subsidiaries in Ireland and the Netherlands.

The reason this is possible is “transfer pricing,” the rules around how much one subsidiary has to pay the other for the intellectual property. The exchanges are supposed to occur at market rates—as if the subsidiaries were an “arm’s length” apart—but generally the sale of the IP is cheap and the rent is very expensive, since establishing the market value of IP is a creative exercise in and of itself.

“It’s not an easy question to tell you how much the patent for any one of a thousand drugs is really worth, or how much the copyright to Microsoft Office is or something like that,” a former US Treasury official says.

The challenge is getting the companies, among the most important to the economic future of the US, to bring their profits back to the US. It concerns investors, as shown in the Dell leveraged buy out and David Einhorn’s crusade to liberate Apple’s cash hoard. It concerns the companies themselves, who have launched a new coalition to push for the end to global taxation and a tax repatriation holiday. And it also concerns US taxpayers, since the government may act to limit companies’ ability to defer taxes on foreign profits—Republicans to finance tax cuts on personal income, and Democrats to cut the deficit.