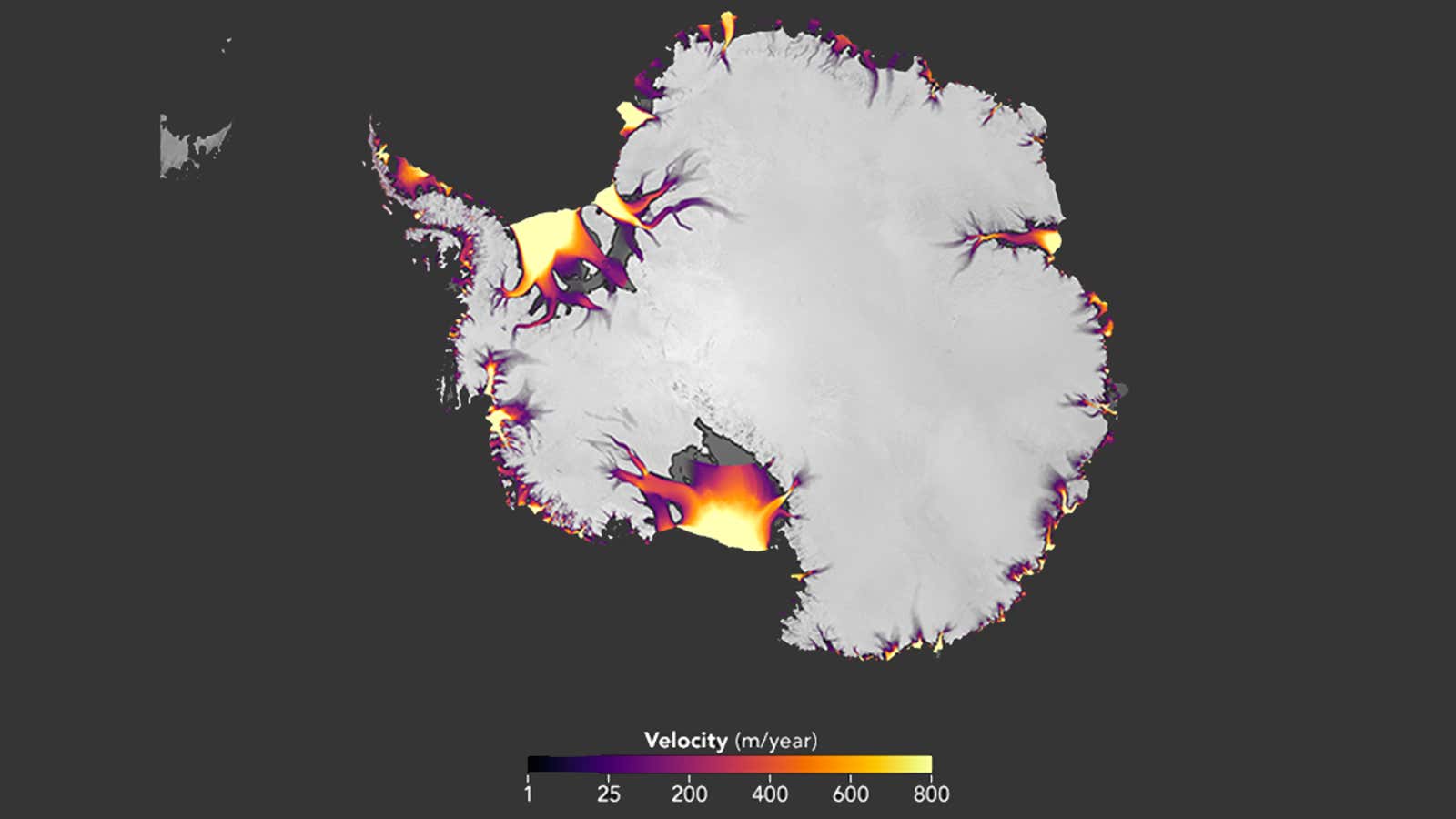

New data analysis confirms what scientists have suspected for a while now: West Antarctic ice melt is speeding up.

In a cutting-edge survey of satellite data published Feb. 13 in the journal Cryosphere, researchers from NASA and other institutions shows that ice loss from the critical region of Antarctica is happening at an increasingly fast pace.

In total, researchers found that Antarctica was losing roughly 1,929 gigatons of ice per year in 2015, the vast majority of which is replaced by new snowfall. But not all of it is replaced by snow, which creates an imbalance that contributes to sea level rise. In 2015, Antarctica lost 183 gigatons of ice that was not replaced by snow. That is 36 gigatons more than the continent was losing per year in 2008. So in total, Antarctica’s ice loss—which can also be viewed as its contribution to sea level rise—has accelerated since 2008. (A gigaton is one billion tons.)

Nearly 90% of that increase in loss occurred in West Antarctica, ”probably in response to ocean warming,” according to NASA. The new data analysis mostly confirms other recent research, but does so with a higher degree of precision by using a new technique that can process a larger amount of satellite data than was possible before.

West Antarctica has been losing a lot of ice in recent years, and at an ever-growing pace, while East Antarctica is losing ice more steadily. The West Antarctic ice sheet is of particular concern because, like a building that stands on an uneven foundation, it is inherently unstable, making it especially vulnerable to the warming climate. If the entire ice sheet were destabilized and melted into the sea, researchers estimate it would lead to 3 meters (9 feet) of sea level rise globally. Models suggest that under a low-emissions scenario, where the world commits to “peaking” and then steadily reducing emissions in the near future, complete destabilization of the West Antarctic ice sheet is possible to avoid. But under medium- or high-emissions scenarios, the loss of the ice sheet becomes inevitable.

The region has made headlines in recent years for major iceberg calving events, like the iceberg twice the size of Paris that broke off from West Antarctica last September. Icebergs themselves don’t contribute to sea level rise; since they float, they’re displacing as much water to begin with as they ever will. But they play the vital role of holding back land-based ice. When icebergs calve, they leave the much-larger region of ice behind them more vulnerable to melt.

Last week, a new study confirmed that sea-level rise is accelerating, rather than increasing at a steady rate. And earlier this week, another study concluded that—much like today’s decisions will determine the fate of West Antarctica—decisions made today about whether or not to curb emissions will have clear repercussions in future sea level rise: For each five-year delay in “peaking” global carbon emissions, median estimates for sea level rise in 2300 go up by 20 centimeters.

Update: This story was updated to clarify that the majority of ice loss in Antarctica each year is replaced by new snowfall; The amount of ice loss that is not replaced by snowfall is increasing, adding to the continent’s contribution to global sea level rise.