A piece of ice two and a half times the size of Paris (or roughly four-and-a-half Manhattans) broke off from West Antarctica over the weekend. It’s not unprecedented, but it has ice scientists worrying.

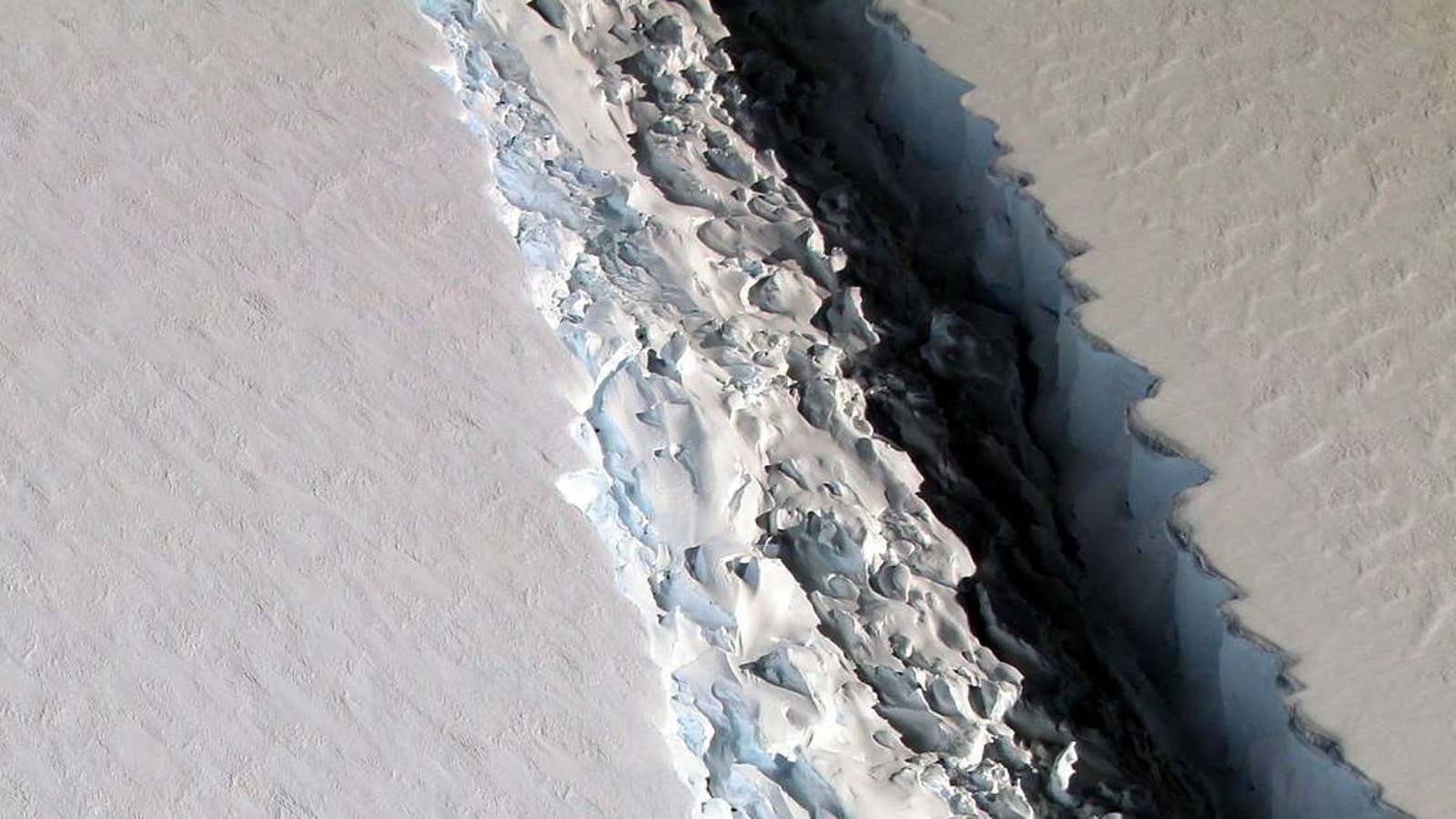

On Saturday (Sept. 23), satellite-observation specialist Stef Lhermitte at the Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands posted an image of the rift, taken from Sentinel1, a European Space Agency satellite.

The ice snapped off from the Pine Island Glacier, making it the second major ice-loss event for that glacier in the last two years. Pine Island is one of Antarctica’s biggest glaciers—and also one of the sites where ice loss has been most dramatic in recent years. This time, the iceberg that resulted from the split is roughly 103 sq miles, or 267 sq km, in size.

When ice separates—or “calves”—from an ice shelf, it becomes an iceberg. When it comes to the future of sea level rise, it’d be much better for all of us if ice shelves stayed ice shelves.

Glaciologist Peter Neff called the event “concerning for future sea level rise.”

But it’s not the size of the iceberg that’s worrying, as Christopher A. Shuman, a research scientist at the Cryospheric Sciences Laboratory at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, explained to Gizmodo. Rather, it’s the fact that a string of recent losses leave the much-larger area of ice behind them more vulnerable to melt.

As the Verge points out, the calved iceberg itself won’t raise sea levels. It is already displacing as much water as it would if it were melted, exactly like how an ice cube floating in a glass of water doesn’t raise the water level when it melts. But ice shelves at the periphery of glaciers serve the important function of keeping the inner, land-bound glacier in place. When the outer blockade of ice shelves fall away (turning into icebergs that eventually melt), the chance of the inner glacier breaking up and melting goes up; because the glacier is on land, it is not currently displacing water. If it parts of it slide into the sea, it certainly will.

If all of Pine Island Glacier melted, it could raise sea levels by 1.7 feet, according to The Washington Post. As we’ve mentioned before, for every 360 billion tons of ice that reach the ocean, sea levels worldwide rise by 1 millimeter. For context, the average sea-level rise per year during the 20th century was 1.7 millimeters (pdf).

Earlier this year, in a much bigger calving event, a trillion-ton iceberg snapped off from another area in Antarctica. Like this event, that part of the ice shelf was already floating in water and will not directly add to sea level rise—but, worryingly, it was part of an icy barrier that holds the massive Larsen-C ice shelf from sliding into the sea.

The loss of that 2,200 sq mile (5,698 sq km) chunk of ice made global headlines, prompting a fascinating array of geographic comparisons to various cities and land masses, depending where in the world you were reading the news.

Read this next: Two Luxembourgs, 10 Madrids, one Delaware: How a giant iceberg is described around the world