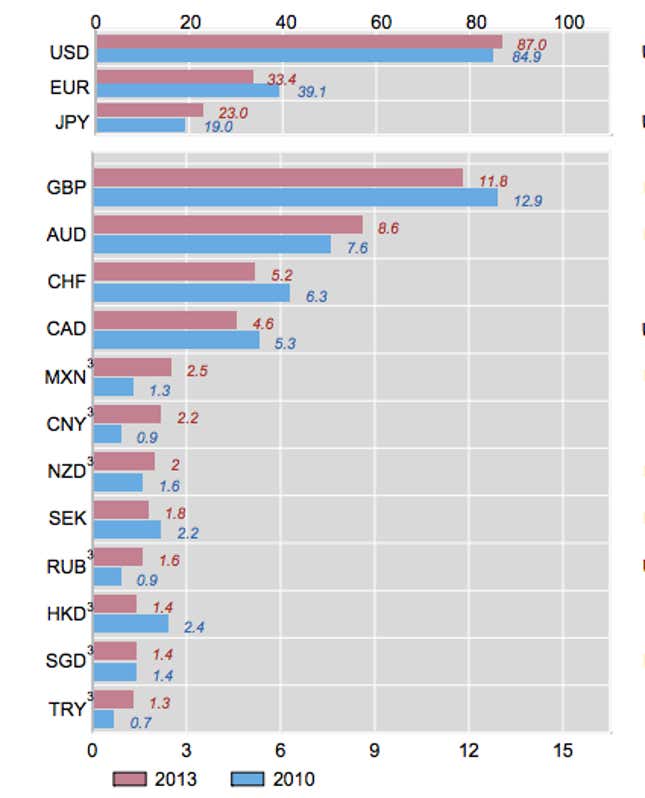

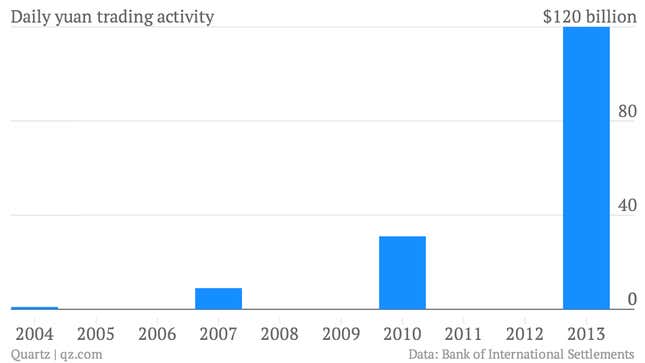

Trading of the Chinese yuan has “surged” (pdf) in the last three years, according to the Bank of International Settlements, with $120 billion now traded each day, up from $34 billion in 2010. In the ranking of the world’s most traded currencies, that drove the yuan from 17th place in 2010 to ninth place this year, leapfrogging New Zealand’s dollar (ranked #10) and elbowing the Swedish krona out of the top 10.

The yuan’s rise is “in line with increased efforts to internationalize the Chinese currency,” said BIS. But as the world’s second biggest economy, the Chinese government wants the yuan to become a currency held in central banks’ reserves and used to settle trade—just like the euro and the US dollar.

When it comes to “internationalization,” the Chinese government talks a big game. As Yi Gang of China’s central bank recently put it, letting the yuan “compete with US dollar or euro fairly in the international market”—thereby ending “discrimination against the renminbi“—is a fundamental policy of the People’s Bank of China.

That has led to hand-wringing about the rise of the “yuan standard” and its threat to the dollar (paywall). But the yuan isn’t remotely close to threatening the primacy of the greenback. And the Chinese government has given little indication that it’s ready to accept the prerequisites for getting it there.

What does “internationalizing” the yuan even mean?

Why would a country want its currency traded globally? An oft-cited reason is so that investors will buy debt issued in the country’s own currency, making it less vulnerable to default in the event of currency swings. But China doesn’t have much external debt, and is showing minimal interest in running a current account deficit any time soon.

Instead China’s leaders seem to have three goals for how the yuan might be used: trade, investment and as a global reserve currency.

The trade rationale is compelling; it would prevent Chinese exporters from losing 2% to 3% on transaction costs and exchange rate losses incurred due to the appreciation of the dollar in the time it takes to settle a trade order. (The Chinese government, which controls the yuan’s value, has let it steadily strengthen against the dollar.)

China’s ambitions for the yuan to be used for investment and as a global reserve currency, on the other hand, have more to do with prestige and bolstering China’s image of itself as a geopolitical leader and a stable, attractive economy. In that sense, the yuan’s global rise is more symbolic than strategic.

The yuan goes global

Internationalization began in earnest just after the financial crisis delivered a double-whammy: a shortage of dollars and a drop-off in global export demand. Those two factors were probably behind the government’s 2009 decision to allow exporters and importers to use yuan in offshore accounts to settle their trades (it expanded that pilot program nationwide in 2012).

As the BIS report shows, that caused an explosion in yuan trading. The growing issuance of yuan-denominated bonds and offshore trading speculation have undoubtedly helped too—not to mention the fact that the BIS began counting offshore trading more thoroughly in 2013.

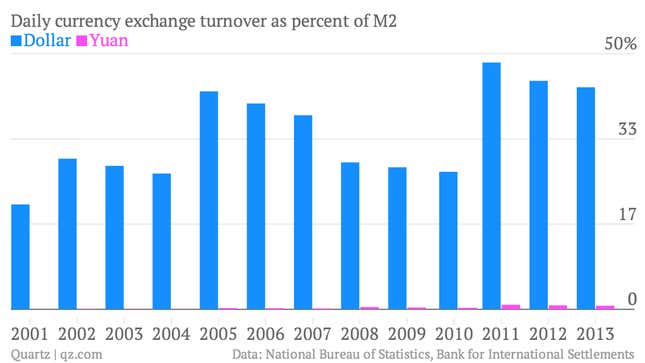

There’s much more room for yuan trade to grow—in the first half of 2013, only around 16.4% of China’s trade was being settled in yuan. If that figure rose to, say, 100%, it would amount to around $730 billion a day, putting it past the British pound’s $630 billion. But even then, trade settled in yuan would only amount to 4.3% of the total yuan in circulation. For the US, that ratio is more like 43%:

It’s really, really hard to get yuan outside of China

Since allowing trade to be settled in offshore yuan accounts didn’t actually get China very far toward its being freely traded, China’s going to have to do a lot more to reach its goals.

For instance, right now, the Chinese government rigidly controls where and how yuan are exchanged, and by whom. The result is that outside of China, yuan aren’t accepted much of anywhere. True “internationalization” can’t happen until that ends, says Patrick Chovanec, chief strategist at Silvercrest Capital Management and an expert on the Chinese economy.

“The real issue with internationalization is opening up the capital account—everything else is just window dressing,” Chovanec tells Quartz. “You can do things to set the stage, but you really can’t see [the yuan] actually playing an international role until it’s internationally useful.”

(On that topic, the yuan convertibility that will supposedly be allowed in the Shanghai free trade zone, as Agence France Presse reported today, is likely another example of “window dressing.” It’s early yet to tell, but it seems that, like the yuan settlement accounts, the government will ultimately wield control over Shanghai’s “offshore” accounts.)

Yuan supremacy: China wants the prestige but not the consequences

But that change will be excruciating. Allowing the yuan to be freely traded would mean that Chinese people could invest anywhere they wanted. Which, yikes. Because it would give Chinese households a chance to invest their $9.8 trillion in savings in overseas markets of their choosing—instead of in volatile Chinese stocks or as low-yielding deposits—opening up the capital account would risk crashing the Chinese stock market or cleaning out the PBOC’s reserves as it defends the yuan’s value.

Here are some other thorny prerequisites for the end of “yuan discrimination”: If China somehow avoided the aforementioned capital flight, it would instead need to run a current account deficit in order to pump out yuan beyond its borders. Chinese workers would lose jobs as the yuan strengthened against other currencies, risking domestic instability. And in order to open the capital account, it would need to let the market set the rates on deposits—something Chinese banks are not sophisticated enough to handle any time in the near future, particularly if they’re competing with foreign banks (which China needs to allow in order to create channels for the yuan to be traded globally). And that’s only the start.

As much as the government wants the prestige of global reserve status, it’s hardly ready to face those risks. But until it does, China can still probably trounce the Swiss franc and the British pound—even without having made much headway on “internationalizing.”