Chinese local governments hit the jackpot this week. In Beijing, Shanghai, Hangzhou and Suzhou, land parcels sold for record prices, crowning a slew of new “land kings,” as Chinese slang refers to record-setting plots. Here’s a roundup of the highlights:

- Beijing: On Sep. 4, Sunac China Holdings paid 73,000 yuan ($11,900) per buildable square meter, or about $1,100 per buildable square foot, for a residential land parcel near the city’s embassy district. (For comparison, the most expensive property deal in Manhattan in H1 2013 fetched $800 per buildable square foot; the average for 2012 was $323.) The total purchase price was 4.3 billion yuan. The developer plans to build luxury apartments and a hospital. Land sales in the capital this year have totaled 109.9 billion yuan—69% more than in all of 2012.

- Shanghai: Hong Kong’s biggest developer, Sun Hung Kai Properties, bought a commercial plot for 21.8 billion yuan. The closing price, equal to about 37,300 yuan per sq m, was more than 24% higher than the starting price. Land sales in Shanghai exceeded 100 billion yuan by the end of August, blowing past last year’s full-year total of 87.5 billion yuan.

- Hangzhou: Yesterday, three developers won bids for different sections of “the last piece of prime real estate” (link in Chinese), shelling out a combined 13.7 billion yuan. The transaction prices ranged between 19,416 and 23,828 yuan per sq m.

- National: From January to July 2013, total land sales revenue hit 2 trillion yuan, a 49% increase on the first seven months of 2012 (which was, to be fair, a low base).

Does this mean supply is scarce?

These prices imply that China is running out of land supply in major cities, though it’s difficult to tell how much supply is in the market because of scarce data. While land prices have soared, the actual plots are getting smaller. In August, developers bought 24.9 million sq m of land in China’s 10 biggest cities; though the area sold was down 0.8% from a year earlier, the value per square meter jumped 151%. And that’s even though major cities have tightened restrictions on home-buying to deter speculators.

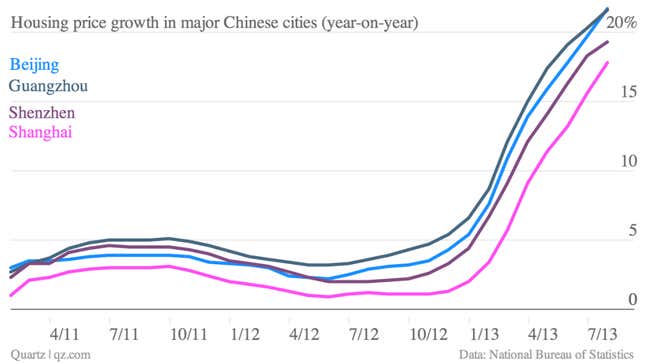

That would also explain why housing prices in big cities continue to soar. Average prices in the top 100 cities rose for the 15th straight month in August.

Actually, it could mean the opposite

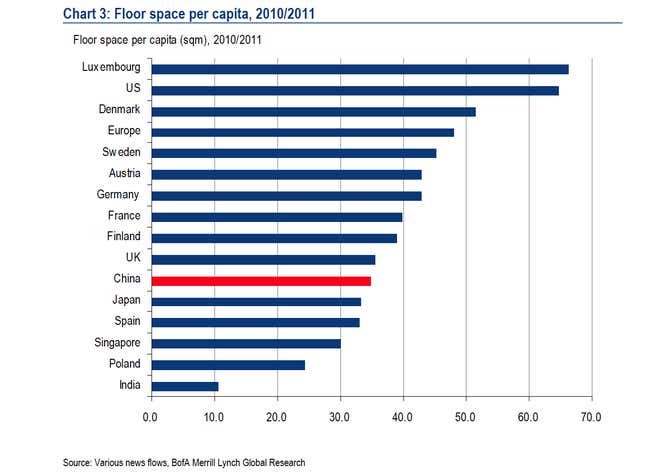

But price rises could be due more to speculation than to a dearth of supply. Especially in big cities, apartments are often seen as investment vehicles more than as homesteads. For instance, even though swanky high-rises are getting more expensive in Beijing, their sales in smaller cities are flagging, suggesting that genuine demand is weak. As Bank of America-Merrill Lynch’s China strategy team noted in March, “China is building too many housing units too fast.” Per capita housing stock, they note, hit 35 sq m in 2011, and is rising by 1.2 sq m a year, putting China in the same league as many wealthy countries:

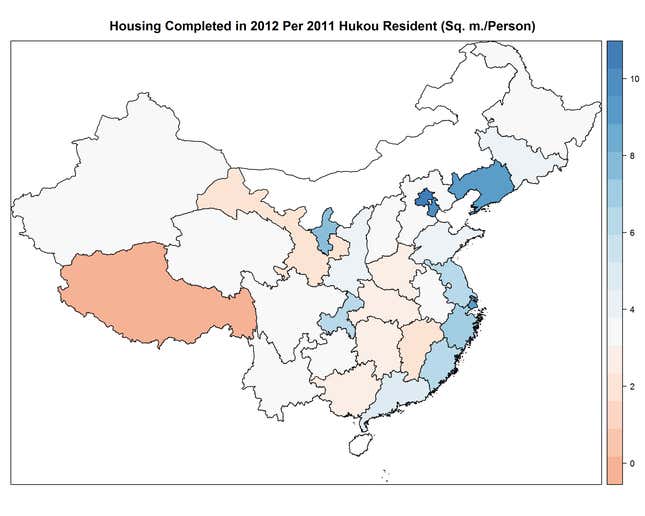

That rate picked up in 2012, even as the housing market slumped that year. Moreover, when you calculate per-capita housing stock not by the general population but by the number of people who hold a hukou, or residence permit, housing completed in 2012 leapt in Beijing, Shanghai and Tianjin, as well as in Liaoning province:

The impact on local governments

As in any country, China’s real-estate market is actually a multitude of smaller markets, each of which has different supply-demand dynamics. Rigid demand in mega-cities like Beijing and Shanghai can probably absorb any excess supply. But oversupply is already hitting smaller cities, and as demand flags, prices have started to fall (link in Chinese). If that fall becomes severe enough to make developers run short of cash, they may discount their inventories in larger cities and cause prices to suffer there too.

If house values fall that could be bad news for China’s financial system, because people frequently use property as collateral. But the greatest impact will be on local governments, many of which now have colossal debt burdens as a result of stimulus spending. Largely unable to issue their own debt because of central government restrictions, local governments depend on selling land (both government-owned plots and occupied plots seized by force) for revenue. In 2011, those sales accounted for more than 60% of local government revenue. As the Heritage Foundation’s Derek Scissors points out, at 5.9 trillion yuan, land sale revenue in 2010 and 2011 alone exceeded the 5.3 trillion yuan total from 1999 to 2008. ”This rate of increase cannot possibly last,” writes Scissors.

Yichuan Wang contributed data analysis and map illustration.