What if someone told you the stock market crashed and spiked 18,000 times since 2006, and you had no idea?

That’s the contention of a group of scientists who study complex systems after analyzing market data, collected by Nanex, since the advent of high-speed trading. While the fallout of computerized algorithms has been seen before, including the infamous 2010 “flash crash,” when markets lost nearly 10% of value in just a few minutes, that same kind of sudden volatility is going on all the time, unseen.

In a new paper called “Abrupt rise of new machine ecology beyond human response time,” researchers found a new trading ecosystem that humans don’t even notice.

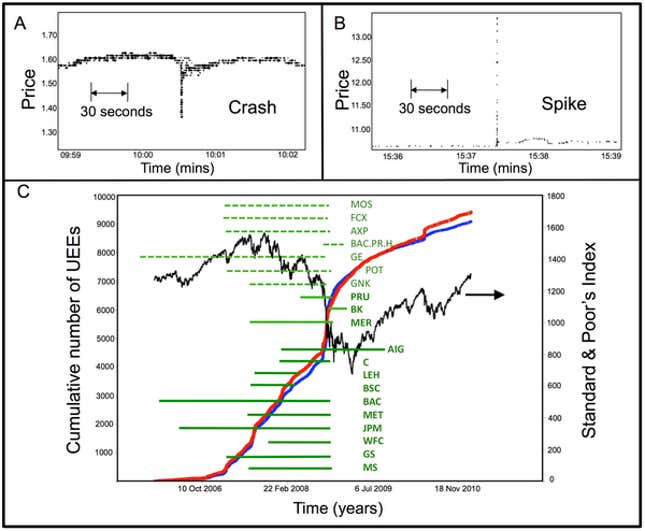

People can’t really respond to stimuli much faster than in one second. The benchmark comes from cognitive scientists who find that it takes 650 milliseconds for a chess grandmaster to realize that a king has been put in check after a move. Below that time period, you can find “ultrafast extreme events,” or UEEs, in which trading algorithms cause prices to change by 0.08% or more before returning to human-time market prices. This appears to be the case when many simple algorithms, operating on limited information, pile into a single trade.

“Down in the sub-second regime, they are the only game in town,” University of Miami Physics Professor Neil Johnson, who led the study, says. “It’s almost like you’re seeing them in pure form.”

This chart shows what an UEE crash looks like (box A), what a spike looks like (box B), and most interestingly, how the number of these events (in red and blue) has risen between 2006 and 2011 compared with the S&P index (in black). That list of stock symbols in green contains the equities that have the most extreme events, with the most likely at the bottom:

If you’ve noticed that the number of extreme events spikes around the time of the financial crisis, and the stocks most likely to experience them are bank stocks, you’ll see why the researchers are so interested in this hidden market: This pattern suggests the coupling between extreme market behaviors and global instability—”how machine and human worlds can become entwined across timescales from milliseconds to months”—and is also are seen more often before and after the kinds of “flash crashes” that people actually notice.

Regulators, though, aren’t keeping track of these events. That’s a problem, not just because of any potential forewarning, but also because trading at that speed creates volatility that makes markets less efficient.

“Are these 18,000 lucky breaks for one of the algorithms or 18,000 examples of a new form of inside trading?” Johnson says. “In terms of the information availability, it’s really hard to tell. It’s sort of strange to have that going on and have nobody know.”

The researchers say there’s much more to learn, especially at the border where human traders and robotic ones interact. One question is whether moving at computer speeds is inefficient because there’s less information available at that time scale—data just can’t move that fast, even electronically. Laboratory experiments suggest computers are more efficient on a human time-scale than a sub-second one. And if sub-second trading does continue, do market participants need to come up with sub-second hedges and derivatives to protect from this kind volatility?

Regardless, the complexity emerging naturally from high-frequency trading tends to be hard to comprehend for market participants and regulators alike.

“It’s sort of a collective, in some sense they all share responsibility and yet nobody’s responsible,” Johnson says. “Am I responsible for the traffic jam out on US 1? No, I’m just in it, but if no one was in it, there wouldn’t be one.”