A generous car-buying incentive program has hit a major pothole in Thailand, which touts itself as the Detroit of Southeast Asia—presumably referring to the auto manufacturing, not crushing levels of government debt—in the latest in a string of questionable stimulus programs.

The $2.5 billion car-buying scheme was similar to the US “cash for clunkers” plan, but without the clunkers—first-time buyers simply received a tax refund of up to $3,200 in an attempt to encourage lower-income Thais to buy domestically made cars.

Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra launched the program after massive floods in 2011 hit the country’s auto industry. Thailand is a regional hub for many car companies, especially Japanese manufacturers such as Honda, Mitsubishi, and Toyota, and autos comprise 12% of the country’s GDP, and at first the plan seemed to work like gangbusters, with 2012 auto production skyrocketing 67% from the previous year.

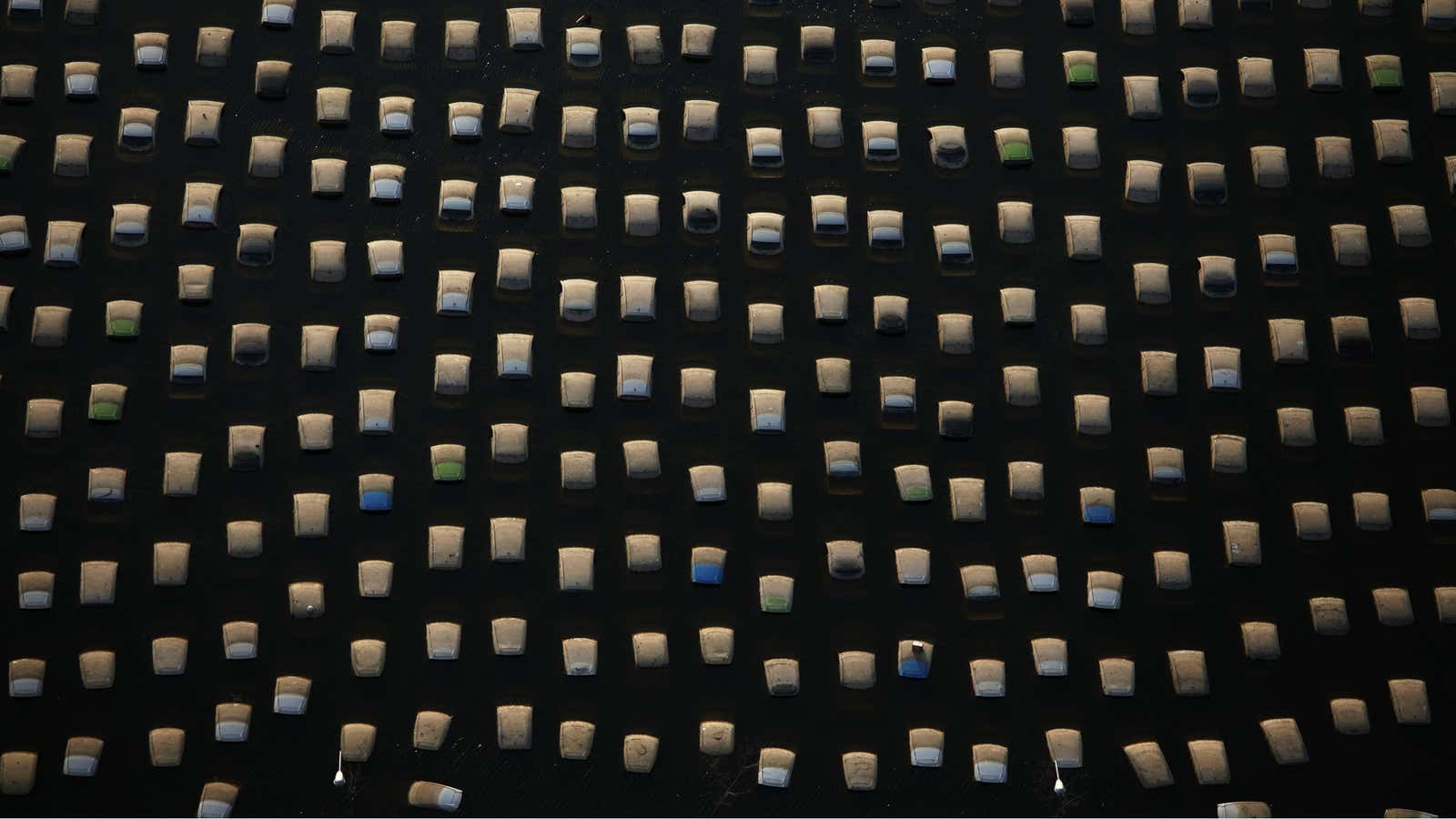

But the problem with encouraging low-income buyers is they often can’t make their car payments. Reuters reported this week that more than 100,000 new buyers have defaulted on their loans, with their cars seized by finance companies. With the resulting used-car glut and the absence of the subsidies, demand for new cars has cratered, threatening the very industry that the plan was meant to help.

“The end of the incentives scheme created an irregularity which may trade off the benefits to some extent. We’ve come to see it as an unavoidable cost of the program,” said Nobuyuki Murahashi, President of Mitsubishi Motors (Thailand), told Reuters.

The woeful outcome shouldn’t have been a surprise—the US cash for clunker program was widely seen as a failure for some of the same reasons in 2009. Unfortunately, Yingluck’s government seems to have a fondness for subsidy programs that don’t make much economic sense.

In an effort to shore up support among rural Thais, for instance, the government pledged by buy rice from farmers at a guaranteed price that was 50% higher than the market rate. The result: about $21 billion in Thai government losses since 2011, not to mention the loss of the Thailand’s status as the world’s biggest rice exporter. Vietnam and India took advantage of the misstep, and Thailand is sitting on a stockpile of millions of tons of rotting rice.

Another more recent economic policy created new subsidies for rubber farmers, who recently clashed with police in protests over their financial plight—after all, rice farmers got government funds; why shouldn’t they? Thailand is the world’s biggest rubber producer, and worldwide prices have dropped more than 45% over the last two years.

Yingluck’s solution, announced earlier this month: $681 million in rubber farmer handouts. It is unclear how this subsidy will lead to anything but more losses for the government, since rubber prices are under persistent pressure due to decreased demand from China and Europe.

The recent economic policies have been costly: Thailand’s debt climbed to 44.3 percent of gross domestic product in June from 38.2 percent at the end of 2008. In June, Moody’s noted that the country’s “increasingly expensive” rice subsidy program is “credit negative,” and threatens the government’s goal of balancing the budget in 2017.

“They’re running out of space because there’s a limit to how much they can borrow fiscally,” Deunden Nikomborirak, research director of economic governance at the independent Thailand Development Research Institute, told Quartz. She noted that “political commitments” like the car buying plan and agricultural subsidies are coming up against the country’s fiscal discipline guidelines, which are stipulated by the finance ministry.

“They’re hitting that limit,” Duenden said.