There’s been a brief resurgence of the idea that if the US Congress doesn’t agree to raise the debt ceiling by Oct. 17, a default wouldn’t be such a big deal. “I’m not as concerned as the president about the debt ceiling because the Fed are the only people buying our bonds,” Republican senator Richard Burr told reporters yesterday—probably surprising the financial sector and foreign governments who actually buy most of those bonds.

But this is wrong on a number of fronts. And the scenario most people think of when they think of a debt going unpaid—namely, creditors knocking on the door—isn’t the only one to worry about.

Rescheduling isn’t an option

First, don’t imagine that the government will be able to pay just the interest on its borrowing if there’s not enough cash for everything. Even if the Treasury could reprogram its clunky payments system to pay bond coupons first, and even if that were legal, a series of large payments due on November 1 would leave the US in arrears. Yipes.

Other than raising or eliminating the debt ceiling, then, the only solution would be some kind of radical action by president Barack Obama, like ignoring the debt ceiling altogether. That would incur a constitutional challenge. Even then, markets might might still question the legal backing of US debt, and one possible outcome is massive spending cuts that plunge the United States into an immediate recession. Which would, incidentally, make it harder to pay down the debt, the very result that freezing the debt ceiling is supposed to prevent.

But many informed people are less worried about that than what might come first: A freeze in the tri-party repo market, akin to the cascade of troubles that followed the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy in 2008.

The tri-party what?

The tri-party repurchase market (pdf) is where investment banks obtain $1.8 trillion in financing every day. In simple terms, it’s like mortgages, only for buying bonds rather than buying houses. In slightly more complex terms, it’s a revolving series of collateralized loans cleared through one of two middlemen, JP Morgan or Bank of New York Mellon. Money market funds, mutual funds and corporations hand over cash in exchange for rights to some kind of collateral proffered by banks and hedge funds who need to buy and sell securities. Typically, these trades are unwound daily.

In 2008, more than a third of that collateral was mortgage-backed securities. When Lehman went bankrupt, its lenders began a “fire sale” of the securities it used as collateral, which drove down the value of other mortgage-backed securities, which led to more fire sales. This dynamic would eventually lead to a freeze in the repo markets, which, at the time, provided $2.6 trillion in funding to the banks each day. The sudden shrinkage in financing helped break the financial system until the Federal Reserve and, eventually, US taxpayers, bailed it out.

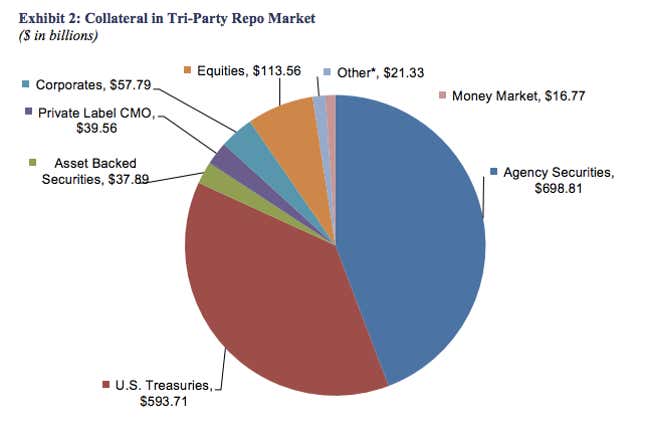

Today, while the repo market is smaller, it’s still important; the New York Fed held a seminar last week about the dangers of fire sales in the repo market. Today, most of the collateral in use is US Treasuries and “agency securities”—mortgage-backed securities guaranteed by the US government:

What could happen if the debt ceiling is reached

Right now, investors are snapping up long-term US debt, seeing it as a safer bet than stocks during the government shutdown. Few, in other words, appear to be taking seriously the prospect that the US might default on that debt. Still, you can see prices for very short-term Treasury bills falling as investors grow leery of owning bills that mature right around the time the US can no longer borrow money to pay them.

But if the ugly day of a default comes, lenders may simply stop accepting US debt as collateral. That will have the effect of sucking some $600 billion in liquidity out of the banking system. Unable to get funding for Treasurys, securities dealers would be pressured to sell them—or other assets—to find new funding, creating a fire sale dynamic. While banks have more capital now and are less reliant on levering up through the repo markets, an adverse situation could resemble 2008.

Even fears of this scenario could put pressure on the financial system. During the last debt ceiling face-off in 2011, overnight repo rates rose some 30 basis points as skepticism about the ceiling increased. So far, overnight repo rates haven’t risen in reaction to the squabbling in Washington, but that’s an indicator we’ll be watching as the debt ceiling deadline draws nearer.

And, of course, this scenario is only about how the Treasurys work in the repo markets. US debt is used as collateral for derivatives swaps and numerous other transactions; if they are suddenly worth less than expected, lenders can be expected to demand more collateral up front, putting even more pressure on the financial system. That’s why pressure is building to raise the ceiling before the world’s largest economy enters a scenario with so much uncertainty.