As we’ve been telling you, the cost of insuring US government debt against default has been surging in recent weeks, thanks to the US government shutdown. If the government doesn’t agree to some solution and vote to raise the US debt ceiling sometime between late October and early November, it will run out of money to fund federal government operations. No money means no payments to the legions of US bond holders, which means default.

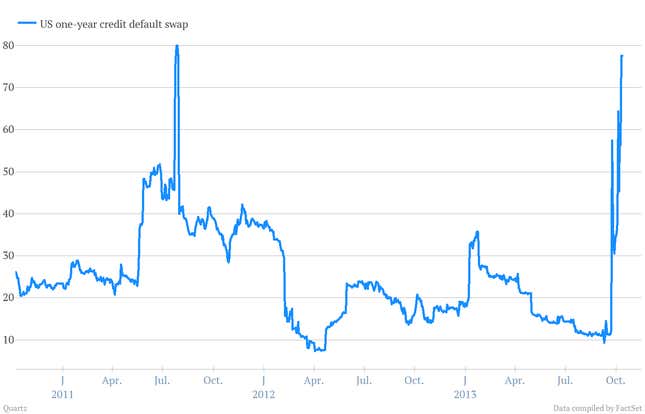

Here’s a look at surging cost for insurance for one year on US government debt, purchased through credit default swaps.

We’ve said before that CDS prices should be taken with a grain of salt, since they are notoriously illiquid instruments. Any big bet by a single entity can move the market.

The Financial Times (paywall) points out that the CDS market is getting a bit more liquid lately. Wall Street trading desks say trading volumes of US CDS have risen from an average of about €1.5 million per day to about €150 million. (Yes, US CDS contracts are priced in euros. The thinking behind that is that any investor who wants to bet against the credit worthiness of the US government would also be leery of holding US dollars.) And large global banks have started providing quotes—that is, the price at which they will buy and sell—on one-year US CDS. It’s the first time in months they’ve done business on those contracts “and are now making 15 to 20 quotes per day. Price quotes for protecting US bonds over the course of five years, traditionally the more popular contract, have roughly doubled to as many as 50 a day,” the FT reports.

The rise in trading volumes on US CDS could mean that more investors are legitimately seeking to protect themselves against the possibility that the US doesn’t pay its bills. Or it could just mean that speculators are merely betting on the fact that the US debt ceiling fight is going to get a lot scarier. These speculators probably don’t have to believe the US will default. They only have to think the crisis will get worse, which would enable them to sell the CDS protection they bought at a higher price (the buyers wouldn’t necessarily have to believe in US default either; they could just be other speculators).

Even so, it’s a sad state of affairs when the once unquestionable full faith and credit of the United States government becomes a plaything for market punters.