Editors’ note: This article was originally published on October 25, 2013. It explains how IEX—the firm profiled in Flash Boys, Michael Lewis’s book about high-frequency trading published today—works to neutralize the advantages high-frequency traders enjoy in the markets.

A plague of predators are eating away at Americans’ retirement funds. But the “Navy SEALs” of trading are here to help.

If you’re like most Americans, then you’re probably not playing the stock market directly. You’ve carefully selected a fund like Vanguard or Blackrock to invest a percentage of your monthly paycheck, and watched the value of your 401(k) pension fund add up over time. In 2010, institutions—including pension funds, mutual funds, hedge funds, etc.—controlled 67% of the stock market, up from 7-8% in 1950.

Unfortunately, the funds investing your retirement savings are also the ones taking the biggest hit from high-frequency traders (HFTs), who make millions by collecting pennies in an enormous volume of trades. While it might not bother you to lose a few cents when you’re making a long-term investment in 10 shares of Facebook, it’s a constant and pricey headache for the funds trading people’s life savings. (We describe one strategy HFTs use here.)

Enter IEX, a new market that says it is owned by some of the United States’ biggest institutional investors (the so-called “buy-side”), and is launching today. Run by a contingent of defectors from RBC Capital, Nasdaq, and various HFT firms—a group IEX chief executive Brad Katsuyama laughingly refers to as the “Navy SEALs” of the trading world—IEX is relying on the people managing your retirement to reshape the market system and clip the high-frequency traders’ wings.

Trading games

It’s important to understand exactly what happens to your money after it leaves your bank account or paycheck (see figure above). Although you may trade a handful of your own money on an online platform like E*Trade, large investors like the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) or Capital Group Companies (the parent of American Funds) prefer to trade through broker-dealers, who can execute their massive orders more cheaply and also provide research, advice, and financing. To avoid moving the price of a stock with a single large order, brokers spread out these orders over a number of different exchanges and “dark pools” (off-exchange markets that don’t broadcast the price of trades and aren’t open to ordinary investors).

Katsuyama says he first started worrying about the effects of high-frequency trading on his clients while he was the global head of electronic sales and trading at RBC Capital Markets, where he and three other IEX executives used to work. He recalls that markets began working differently in 2007, just after the US Securities and Exchange Commission introduced Regulation NMS—a controversial rule that many argue has spawned the rise of high-frequency trading.

Clients would tell Katsuyama to buy certain stocks. Staring at his computer screen, he’d pick from a list of algorithms that would optimize the way his order was executed on a variety of exchanges, trying to get the highest percentage of the order executed at the best price possible. But whereas he used to see nearly 100% of his orders fulfilled, suddenly he found that only 60% were being executed. Before 2007, “things would happen randomly but it didn’t feel systematic,” he tells Quartz. After, “it got unbelievably frustrating that, day-in and day-out, I was getting screwed.”

The hammer of THOR

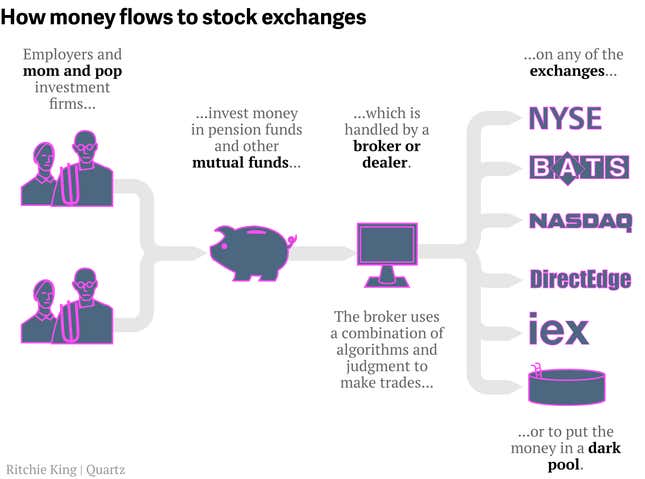

Although the many of the US’s 13 stock exchanges are nominally based in New York, they really live in New Jersey, where their servers occupy nondescript data centers.

Servers for BATS, the closest exchange by distance to New York City, live in a data center in Weehawken, right across the Hudson River from downtown Manhattan. DirectEdge—another electronic exchange—stores its servers 4.6 miles away in Secaucus. Nasdaq’s servers are in Carteret, and those of the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) are, ironically, the farthest away, in Mahwah. An order placed at the same time in New York will arrive at each of these in sequence (see above).

When Ronan Ryan, now IEX’s chief strategy officer, joined RBC Capital in 2009, it took a signal from RBC’s Manhattan router about three milliseconds to travel to NYSE. He and his colleagues soon discovered the reason for Katsuyama’s frustrations.

If a client wanted to buy 10,000 shares of Netflix, Katsuyama might send an order out to all these exchanges to buy shares at $330.00. Some of these orders would be filled almost immediately at BATS. But servers belonging to HFT firms “co-located” (housed in the same data center) with each exchange, registering that Netflix was trading for this price, would send a blast of orders ahead to DirectEdge, Nasdaq, and NYSE, and beat Katsuyama’s trade to the punch; despite heavy investments in hardware, RBC’s infrastructure was still slower than that of the HFTs. These new orders would boost the price of Netflix shares to $330.01, and Katsuyama’s order would come back only partly fulfilled. He’d send the order back out to buy at $330.01, knowing that high-frequency firms were likely making a pretty penny by boosting the share price.

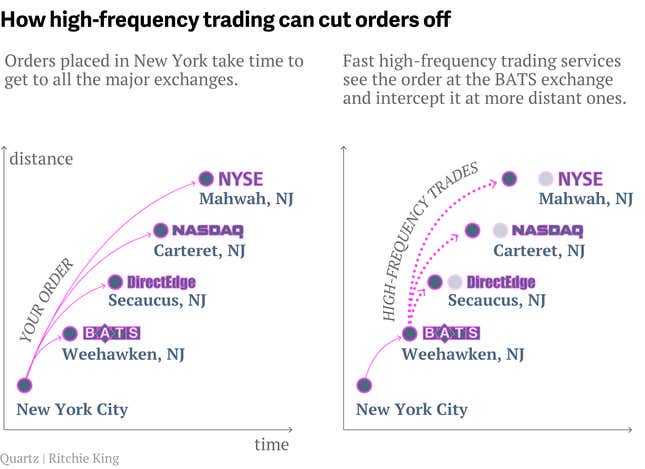

The team at RBC Capital soon developed a solution—a new trading technology dubbed THOR. To prevent high-frequency firms from jumping ahead of their trades, they staggered the timing of their orders to different exchanges. An order sent to NYSE, the farthest exchange, would go out without a lag, but the same order to a nearer exchange like BATS would be timed to go out microseconds later, so that they would arrive at all the exchanges simultaneously. The technology, launched in January 2011 (paywall), effectively neutralized the HFTs’ faster wiring.

THOR was an immediate success. “We took on 450 new clients in just those first 18 months,” recalls Ronan, who joined RBC Capital in 2009. “That’s unheard-of.” Katsuyama says he returned to fulfilling almost 100% of his orders. “We were explaining to [clients] why they had been getting screwed. It was really easy to sell [RBC’s services],” he told Quartz.

Market mania

THOR only served clients that executed their trades through RBC’s traders. But Katsuyama, Ryan, and their team knew more investors would want access to a system that put them on equal footing with HFTs. The way to offer it to them was to leave RBC and start their own dark pool—IEX.

Why start another dark pool when there are already more than 50 exchanges and dark pools operating? IEX believes its competitors have one flaw: misaligned incentives. Because there are so many markets to trade on, brokers tend to choose those that have the highest volume of trades going on. Most dark pools are owned by broker-dealers or banks, which in the attempt to maintain volume, are loath to send their orders to other venues. And their need for volume makes high-frequency traders, who execute a massive number of trades, excellent clients. So these exchanges offer them perks: order types that give them a particular advantage, rebates, and technology.

But some HFTs employ “predatory” strategies to make the extra penny or two per share: things like flooding a market with orders to change a stock’s price, jumping ahead of other investors, or trading with only certain kinds of investors. These tend to work against the interests of the investors themselves, who just need their trades carried out; they may not get the best prices.

As a result, IEX believes, existing exchanges and dark pools market their services towards intermediaries like brokers and HFTs, not the actual investors who drive corporate growth. ”What I think is lost on people is that the investor’s order is actually far more important than the intermediary’s order,” reasons Katsuyama. “If all investors stop trading, there would be no volume. If the HFTs disappeared, there would still be trading, like there was many years ago.”

So IEX takes the opposite approach. Its sales pitch is aimed at funds, which it sways with a promise to prevent predatory HFTs from hijacking their orders.

Action at a distance

IEX’s solution for keeping HFTs at bay is remarkably elegant. It doesn’t ban them. It merely slows them down a tiny bit.

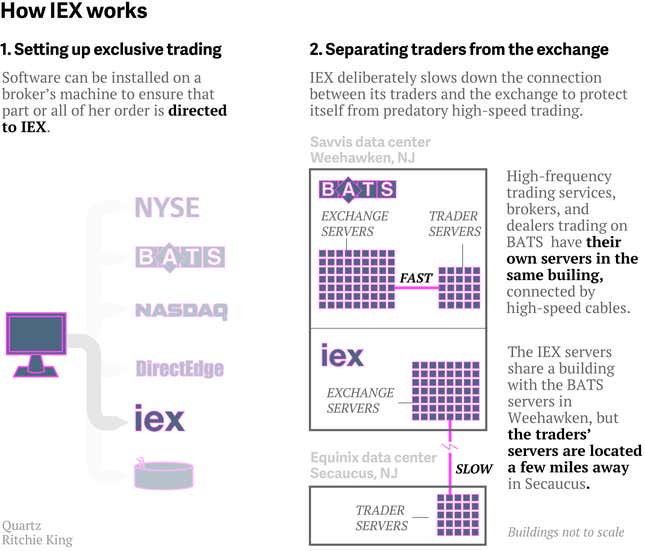

Most exchanges allow broker-dealers and HFTs to house their servers right next to the exchange’s own servers that carry out the trades. The result is an almost instantaneous transmission of information about what trades are executing. That gives HFTs a momentary advantage that they combine with raw processing power to get an edge over other players.

IEX has space for broker-dealers and HFTs to store their servers too. But not next to the trading servers; farther away, in another building. This adds a crucial delay. It takes orders 350 microseconds to travel from one building to the other, 250 microseconds to execute, and another 350 microseconds to send back confirmation. All told, that’s 950 microseconds, or just under one millisecond. IEX thinks it’s enough to stop HFTs from peppering the exchange with orders that can help it predict investor behavior.

IEX also eliminated all but four of the hundreds of order types exchanges offer brokers.

“We’re trying to put the greatest number of people on equal footing,” says Katsuyama. “There’s a huge swath of participants that these [950] microseconds is meaningless to but it has huge meaning to a very small group [the HFTs],” he adds. The point is not to prevent HFTs from doing a lot of the things they normally do—such as trading on small differences between a gold exchange-traded fund and gold futures, for example. It’s just to stop the predatory strategies that make them money at the expense of real investors.

A new kind of exchange

Like other dark pools and exchanges, IEX will have to draw volume to succeed. But because it’s owned by the “buy-side”—the investors—rather than by brokers, and because it thinks it can beat predatory HFT strategies, it’s hoping that investors will flock to it, bringing all the volume it needs.

IEX says it’s owned by a consortium of institutional investors, though only Capital Group Companies and Brandes Investment Partners are public about it. It also has 19 brokers as “subscribers,” meaning they can route some or all of a client’s order to IEX, but don’t have an ownership stake.

Still, it’s hard to get volume when you don’t have any to start with. So Ronan and Katsuyama have embarked on a massive sales pitch, circumventing brokers and attempting to sell their brand new market to pension funds, mutual funds, and other institutional investors. But they’re trying to get brokers on board too, by offering them an incentive called “broker priority” or “broker preferencing”.

The way it works is as follows. Let’s say that clients of both Wells Fargo and Barclays want to sell IBM shares at $176.00, and both brokers submit sell orders to IEX, but Wells Fargo’s order gets there first. And let’s say that shortly after, Barclays submits an order from another client to buy IBM at that price. Typically, on a US exchange, the first sell order to be submitted would be the first one fulfilled—in this case, Wells Fargo’s. But under “broker priority,” the brokerage that sent in the buy order—Barclays—gets to match it up with its own sell order.

This kind of matching just isn’t done in the US, but it is commonplace in Canada. In IEX’s case, it gives brokers an incentive to trade on the same exchange—IEX—rather than splitting their orders around various dark pools. According to IEX, the likelihood that two matching client orders will ever find each other in a dizzying maze of dark pools and exchanges is just 6%.

IEX has some prominent critics of HFT on board. One of them is Sal Arnuk, a co-founder of Themis Trading, an IEX subscriber. “I’ve been waiting for something like this for a long time,” Arnuk told Quartz.

Still, there’s no guarantee that either strategy—pitching straight to investors or broker priority—will pay off. ”Do you need another venue? Will the market support it?… It really depends on the commitment and trust that their owners put into their venue,” Sayena Mostowfi, a senior analyst at TABB Group, says of IEX. “If they trust it then it could definitely be successful.”

IEX will go live as a dark pool, which doesn’t display trading prices publicly. Its management will apply for designation as an Electronic Communication Network (ECN) early next year; although this wouldn’t make it a full-blown exchange, it would publicly display quotes for shares. If all goes well, then IEX could one day become a national exchange. Its founders harbor hopes of expanding internationally and beyond stocks into other kinds of assets, like foreign currency or bonds. ”If [institutional investors] make a decision to take ownership of their order, it will work. If they don’t we’re back to the drawing board,” says Katsuyama.