Some 20 employees crowd into TransferWise’s office. Most of them sit at large white desks arranged in tightly packed rows. A few work on the couches by the door. Taavet Hinrikus, who founded the fast-growing international-money-transfer service, expects to hire ten more people in the next three months. He needs a new office. But “most landlords want you to sign a five-year lease,” he says. “In five years’ time, I either need room for 200 people or none at all. But today I can’t afford to sign a lease for 200 people.”

It is a typical story. There is an inherent tension between the needs of the tech industry and those of big landlords, which include property developers, insurance and pension funds, and investment funds. Start-ups prize experimentation and move on if it doesn’t work out. Landlords value stability—and a nice, steady income—above all else. Yet they know the biggest growth in the next few years will come from tech firms.

The virtual economy’s physical needs

Some 250,000 people work in the technology-media-telecommunications (TMT) sector, according to Savills, a property consultant. That will rise to 300,000 by 2016. All those people need somewhere to work. Despite the notion that tech companies have fewer employees and need less space, most of them are as tied to physical property as industries of old. The difference is that space for nurseries, cafeterias and ping pong tables is as important as desks or assembly lines. But the purpose is the same: keep people at work and make them more productive. The staff need to be attracted to the building, says Simon Allford of Allford Hall Monaghan Morris, the architects designing Google’s new London headquarters

In theory, this is great news for developers. The highest yields on London office properties currently run at 4%-5% a year, according to Patrick Scanlon, who researches commercial property for Knight Frank, another property consultancy. Few other assets offer such reliable yet safe returns.

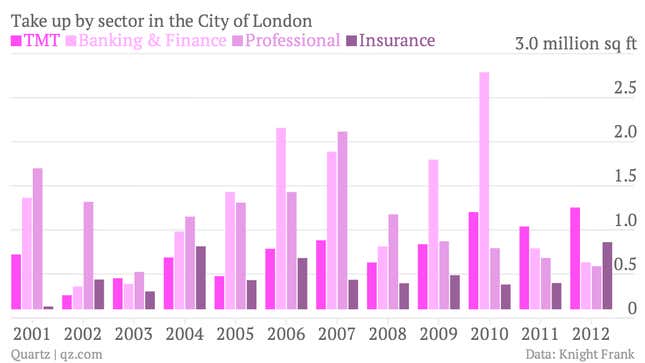

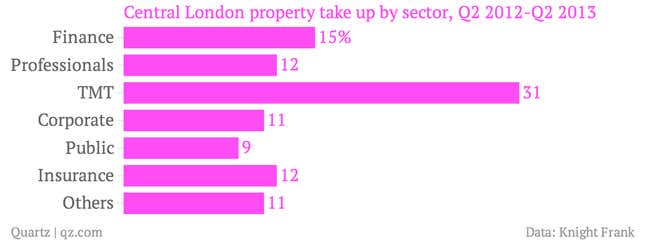

Large tech companies are indeed causing plenty of excitement in London’s property market. Amazon will move to a 12-story, 210,000-sq-ft (19,500 sq m) headquarters in central London later this year. Google is relocating from three offices in Central London to a 1-million-sq-ft headquarters between St Pancras station, where the Eurostar leaves for Paris and Brussels, and Kings Cross station, 45 minutes to Cambridge, the heart of Britain’s computer hardware industry. (Google also has a co-working space in Shoreditch, but that will remains where it is.) In the 12 months to the end of June, the TMT sector absorbed nearly a third of all available property in central London, up from 14% in 2001, according to figures from Knight Frank. The sector’s share of the central London leasing market tripled between 2006 and 2012.

Why Chinese restaurants go to Chinatown

The problem is that there is only one Google and only one Amazon. They can sign long leases and choose where to put their offices. The vast majority of tech firms have no such luxury. Not only are they unable to guarantee mere survival; they also can’t afford to be picky. Start-ups need to be close to other start-ups. Such clustering, as property types describe it, is essential because visiting investors tend to tour the neighborhood; being far away could mean missing out on a crucial meeting. The same mechanics drive hedge funds to Mayfair and Chinese restaurants to Chinatown.

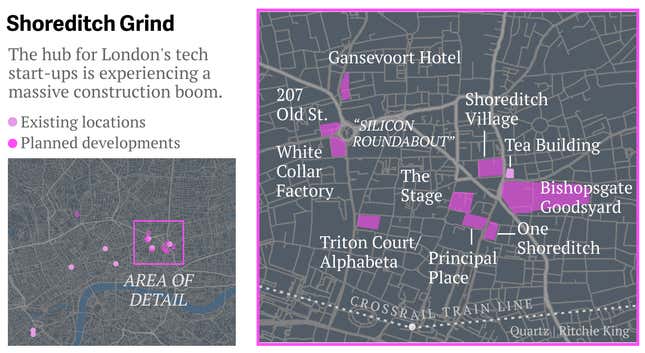

But Shoreditch, the east London neighborhood where the startups cluster, is not fit to be a hub of commerce. Like much of east London, it was an industrial area with working-class housing. Old factories and warehouses—such as the Tea Building (pictured above), in which TransferWise has its office—have been converted, but there remains a crunch for space. The biggest impediment to the networked, online economy Britain is keen on building may be the most physical, tangible one of all: finding a place to work.

The way to disperse a cluster…

That is beginning to change. Across London, property developers are becoming investors, data-center operators are becoming property developers, big landlords are adapting their business models, and a vast amount of construction is kicking off. The technology sector is changing the very face of the city.

“London is developing like Silicon Valley,” says Juliette Morgan, a property specialist at the Tech City Investment Organisation, a body set up by the government to promote investment in London’s tech scene. The similarity between wet, gray London and the verdant valley is not immediately obvious. But Morgan is referring more to the series of disparate nodes, or clusters, that form part of a larger network than to the weather or the scale.

…is to create lots of new ones…

Some four miles south-east of Shoreditch is Canary Wharf, a 1980s development filled with financial-services firms. Sterile and skyscraper-filled, it is the very opposite of achingly trendy Shoreditch. But the Canary Wharf Group (CWG), which redeveloped disused docklands into the business district it is today, is confident it can attract start-ups to its glass-and-steel towers. “A lot of developers are realizing that the TMT sector can help you fuel a lot of growth because it’s a high potential, high growth businesses,” says Eric van der Kleij, who heads Level 39, Canary Wharf’s incubator on the 39th floor of the district’s tallest building, 1 Canada Square.

The plan is not to compete with Shoreditch but to complement it. Level 39 is meant for start-ups serving the financial sector. By helping grow new companies rather than waiting for big ones, it hopes to profit from that growth. As the start-ups become bigger, they move up to the 42nd floor where they rent space. A real success might one day occupy a floor, or even a building at the new 4-million-sq-ft Wood Wharf development adjacent to Canary Wharf. Kleij calls it “property as as service.”

Canary Wharf’s plan is a fresh take on the old idea of incubators. It is a well established practice for venture capitalists to provide their start-ups working space. For example, Passion Capital, a British venture-capital firm, helps start-ups in its portfolio get around the problems of long leases by operating White Bear Yard, a building in Clerkenwell. That keeps the landlord satisfied—an investment fund is a reliable tenant—and saves start-ups the distraction of looking for space. The difference is that most VCs hope to sell off their stake in a firm as it gets bigger. Canary Wharf just hopes their start-ups get bigger and bigger.

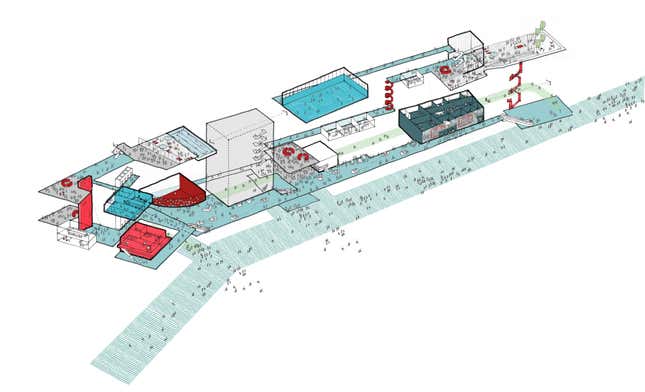

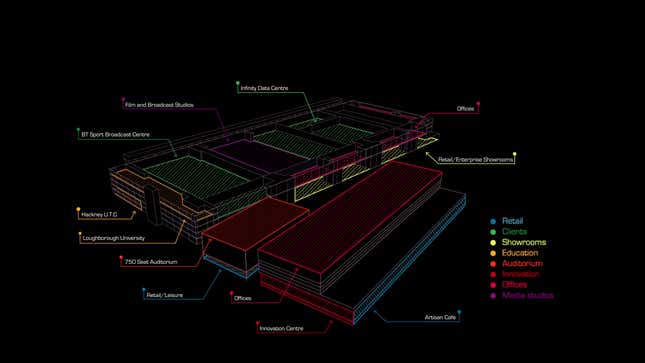

At the Olympic park at other end of town, the media center is being converted into iCity, a 1-million-sq-ft “digital quarter”. The project is the work of Infinity, a data center company, which later tied up with a developer. BT Sport, a new television channel, is already broadcasting from its new studio at iCity. Loughborough University will soon open a new campus there. The plan is to attract the new wave of start-ups specializing not in apps and websites but in hardware, 3D printing and electronics, according to iCity’s Richard Gibbs. Like Canary Wharf, iCity is not interested in competing with Shoreditch: It hopes to make its own cluster from the ground up.

Canary Wharf and iCity are miles away from Shoreditch but what they share in common with it is that they will all be easily accessible by Crossrail, a new high-speed underground rail link that will connect London to its far-flung suburbs. When trains start running in 2018, the ride from Canary Wharf to Heathrow will take less than 40 minutes. The same journey on London’s aging underground network today takes over an hour on two connecting lines.

…and refit the old ones for the new world

Shoreditch hasn’t been forgotten among all this expansion. The area is about to undergo a transformation. Roughly a dozen developments are planned for what is a fairly compact, low-rise neighborhood; many of those are planned as soaring towers. A lot of the development is clustered to the east of Shoreditch, which will see a copse of new towers, a mixed-use block called Shoreditch Village, and the redevelopment of a goods yard. The other center of action is the Old Street roundabout, for which early start-ups self-deprecatingly named London’s tech scene “Silicon Roundabout” (lately rebranded to “Tech City” by the government).

Derwent London is one of the developers on the roundabout. It is often cited by London’s property professionals as a landlord that knows how to take care of its clients and understands the shifting nature of its business. It is about to start construction on the White Collar Factory, a 15-story tower with a clump of smaller buildings surrounding it. The developer hopes to attract a big firm to the tower, but will offer flexible terms—short leases, options for breaking contracts early—in the other buildings. The idea, like at Canary Wharf, is to allow start-ups to grow within Derwent’s offerings. Think of it as the cloud-computing model—where companies lease just as much server capacity as they need at a given moment to run their websites or process their data—only applied to property.

But it will take a while. TransferWise is unlucky to be growing so fast at a time when all these developments are still in planning. Only when more buildings open up will these pressures lift. In the meanwhile market realities rule. “Ultimately, we have shareholders to answer to,” says Emily Prideaux of Derwent’s leasing team.

No going back

On the narrow street where Google’s headquarters will rise, the temporary walls that separate the construction site from the road are covered in graphics and slogans. “A particularly magical ingredient makes some cities great, and leaves others as mere over-sized towns,” one particularly philosophical wall reads, going on to reveal that the ingredient is trade.

This is hard to dispute. More important is that the nature of trade changes and cities must adapt. London, like Paris, could very well have fallen victim to stagnation. Instead its transformation over the past few years has been spectacular—but it cannot stop changing just as the global economy is re-inventing itself.

Old-time Shoreditch residents are tempted to pass off “tech city” as another fad, like earlier ones for vintage clothing shops and Prohibition-style speakeasies. They are wrong, say the developers. ”The area has a lot of detractors, people saying it’s a bubble,” says Knight Frank’s Scanlon. “I don’t think it is a bubble. You can’t reverse technology. I don’t think anyone is in any doubt that in 10 years time the tech sector will be one of London’s most important occupier groups. It’s just a question of how big.”