Bad loans are finally floating to the surface. China’s “Big Four” lenders—Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, China Construction Bank, Agricultural Bank of China and Bank of China—reported a combined 329.4 billion yuan ($54 billion) in bad debt, based on their unaudited Q3 earnings. That’s the “biggest increase in soured loans since at least 2010,” said Bloomberg, and brings their combined bad loan ratio to 1.02%.

Of course, that’s teeny for a country that’s supposed to be teetering on the brink of a debt crisis—and up only a smidgen from the 1.01% in December 2012. But ICBC and CCB traded down on Thursday (Oct. 31) in Hong Kong, while ABC and BOC only saw paltry bumps.

That’s not necessarily because of the banks’ bad debt ratios. No, the more obvious concern is that though the Big Four continue to be the world’s most profitable banks, their profitability is steadily shrinking.

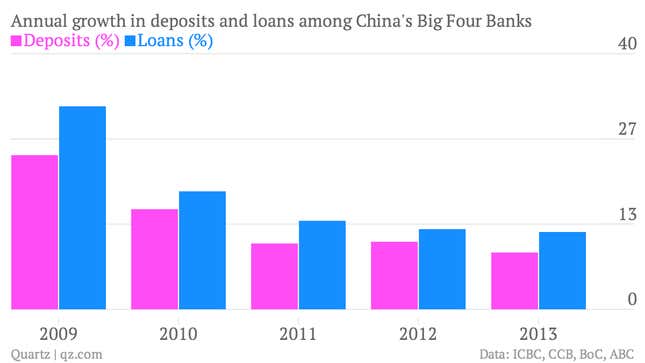

And that says something much more worrying: people are less and less willing to save their money in Chinese banks. In fact, deposits at the Big Four fell by 1.3 trillion yuan (link in Chinese) in the first 27 days of October, reports Caijing. With less of a base to lend from, they lent only a combined 93 billion yuan in October. That compares with a monthly total of between 370 billion and 208 billion yuan in 2013 so far. Here’s how the trend for the last few years looks:

In other words, the twilight of easy profits is falling fast. The Big Four’s business has boomed largely because, being state-owned, they have easier access to cheap deposits—the government sets deposit interest rates artificially low, currently 3.25%—which they turn around and loan to the biggest, most reputable state-owned enterprises (SOEs). But as growth slows, sound loan candidates are growing fewer.

Meanwhile, Chinese companies that can’t roll over loans—or order banks to lend to them—are so desperate for credit that they are taking out shadow loans, meaning money lent off bank balance sheets. Would-be depositors are lending to them because this guarantees much higher interest rates than the paltry 3.25% they can collect at commercial banks. Banks had been able to take advantage of this by in effect securitizing those higher-yield loans as “wealth management products,” a form of deposit from which they could profit without recording it on their balance sheets. But the banking regulator has been cracking down on that business of late.

Until banks write down bad debts, that supply-and-demand balance will only intensify, draining more deposits from the system, eroding the lending base with it. Fortunately, the Big Four are finally starting to recognize bad loans and provision for future write-downs. ICBC, for instance, wrote down 22.1 billion yuan in the first half, reports Bloomberg, up from 7.65 billion yuan in H1 2012. We’ll get a better sense when the banks give more detailed accounts in their annual report.

Writing down debt will likely mean that banks will need new equity, diluting their shares’ value. While the current ratio of bad loans tells us little about that likelihood, the local government audit, which should be announced sometime next week, may offer a rare glimpse at roughly how much bad debt the government is willing to admit is out there.