Here are the signs that China’s Lehman moment is inevitable

Money market rates in China climbed again last week, prompting more worries of a deja vu of June’s cash crunch that spooked global markets. That was when the Shibor—the Shanghai interbank offering rate, which tracks the interest rates banks charge each other—soared, reminding many of the Libor leap that happened just before Lehman’s demise in 2008.

Money market rates in China climbed again last week, prompting more worries of a deja vu of June’s cash crunch that spooked global markets. That was when the Shibor—the Shanghai interbank offering rate, which tracks the interest rates banks charge each other—soared, reminding many of the Libor leap that happened just before Lehman’s demise in 2008.

The likely cause is that the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) declined to inject funds into the interbank market for a third time in a row Friday. Cash will get even scarcer this week, when banks move cash back onto their balance sheets to meet reserve ratio requirements. For that reason, the PBOC will likely open its tills on Tuesday, soothing the Shibor once again.

The Shibor is useful, says Patrick Chovanec, chief strategist at Silvercrest Asset Management, “because it’s the part of the iceberg that we can see.” Below the surface, however, are far more alarming signs of the state of China’s economy, according to a recent note by Anne Stevenson-Yang of J Capital Research in Beijing. What her research reveals about the source of China’s liquidity suggests that, regardless of China’s 7.8% Q3 GDP growth, a Lehman-like bank failure is more likely than ever.

Deposit farming

First off, bank deposits, which form the lending base for banks, are growing at a slower and slower clip. That’s largely because the government sets those rates artificially low, prompting households to shift funds into high-yield wealth management products (WMPs) and other products that make up China’s shadow finance system—credit channels that exist off bank balance sheets and beyond regulator oversight.

Loan officers are now working overtime to meet quotas for deposits, not loans, says J Capital. When they can, they pass on this work to companies hard-up for credit, requiring them to find depositors willing to put enough of their money in the bank to cover the amount of the loan they need. To lure depositors, the borrowing company offers to pay interest directly to depositors, which supplements the government-mandated 3.5% rate the bank pays on deposits. Depositors therefore reap up to 8% yield—way higher than the measly 3.5% for the deposit. This is so widespread that it’s given rise to a specialist trade in “deposit farming”—i.e. brokering depositor recruitment—which has cropped up on street corners around China, reports J Capital.

A pyramid made of quasi-money

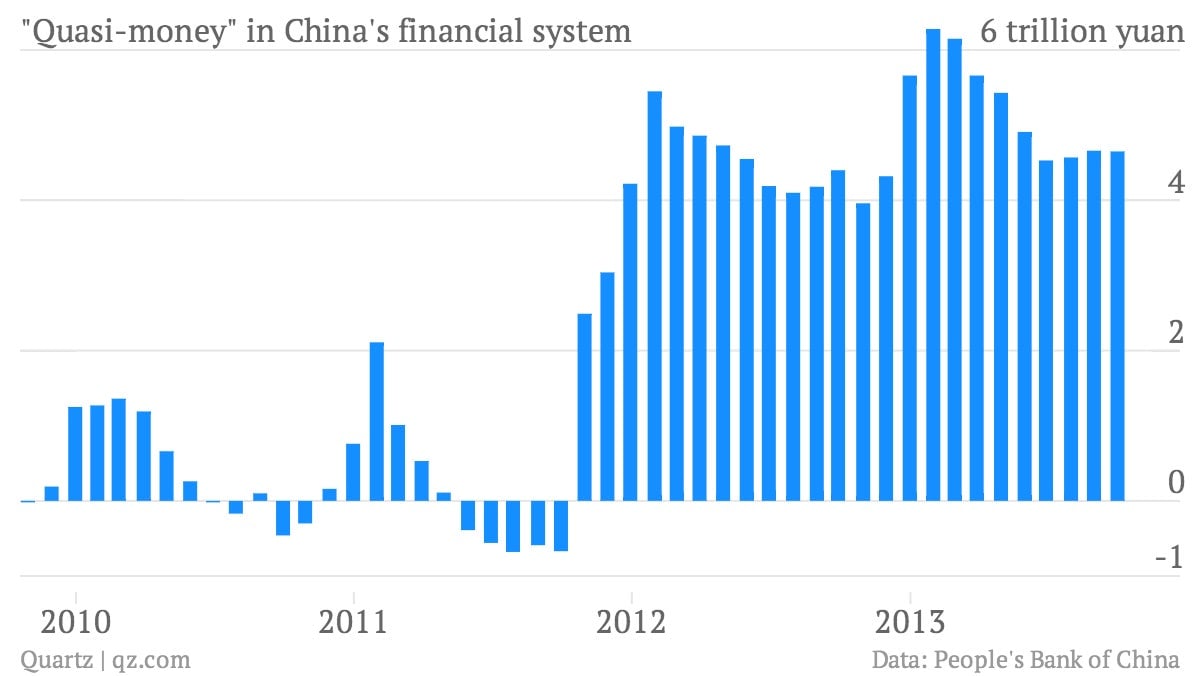

If deposits are so scarce, how have banks been able to pass the audits at the end of each month, which is when they must meet reserve requirement ratios? By using “quasi-money”—fairly liquid financing instruments that include wealth management products which securitize off-balance-sheet lending, and discounted bank acceptance notes. The latter is a promise of a future payment; businesses can cash them in at a discount before the payment is due. Through repurchase agreements with other banks, they can be wiped off bank books while boosting a bank’s deposits.

Nearly three-quarters of deposits are now made up of this “shadow currency,” according to J Capital research, as quasi-money creation has expanded faster than growth in deposits. That creation is happening without even the pretense of having a claim of a future payment. One bank manager in Hebei province told J Capital that it printed bank acceptances “on demand” for a local government finance vehicle (LGFV) whenever the platform needed to pay existing loans.

Banks that are lower on the finance food chain—smaller ones that don’t enjoy state backing—are profiting as middlemen in this trade. A source close to the banking industry in China tells Quartz that 40% of the profits of a Hong Kong-listed commercial bank now come from brokering the brisk trade in bank acceptance notes.

Where is all the “shadow currency” going?

We recently discussed Société Générale’s estimate that 39% of China’s GDP—or around $3.4 trillion—is going toward old debts. That roughly squares with J Capital’s calculation that 60% of new credit is being used to pay off old loans, and as much as 80% in some regions.

This is happening for a couple of reasons. Contrary to China’s recent economic data, growth is foundering. In interviews and surveys, business managers are “absolutely blunt about how national statistics obscure the reality before them,” says Stevenson-Yang. As a result, revenue is falling even in sectors that haven’t traditionally been hooked on credit.

But while companies in those sectors are cutting costs and liquidating assets to pay down loans, state-owned companies and LGFVs are piling on more debt. Because everyone assumes that the central government guarantees their loans, they have “infinite demand for credit,” says Silvercrest’s Chovanec, and will spend what they have to to hit growth targets. That’s especially true for infrastructure projects at the local level, he adds.

What happens next?

Despite this grim outlook, Shibor’s latest lurch will probably only be temporary. What it shows, however, is how sensitive China’s financial system is to even the slightest hiccup in cash creation. That means if the government cracks down aggressively on the shadow currency trade, consequences would be dire.

Of course, something has to give eventually. J Capital’s Stevenson-Yang sees two ways this might happen. “The economy is either going to skid into a long period of no growth,” she tells Quartz, or a bank will fail, accompanied by an economic crisis. But it’s futile to try to guess when the latter will happen, she says. ”You just can’t time these things. The whole point of the system is that they control the visible signs because it matters a lot that the banks not be looking like they’re failing.”