How China’s unsuspecting savers are funding the nation’s risky credit boom

Chinese bank loans dropped sharply in December, falling 29% year-on-year. That should be good news for the health of the financial system. Bank balance sheets are still choked with loans they made in 2009-10 (paywall) under orders from Beijing to keep China growing through the global crisis. December’s lending letup appears to signal an easing of this trend.

Chinese bank loans dropped sharply in December, falling 29% year-on-year. That should be good news for the health of the financial system. Bank balance sheets are still choked with loans they made in 2009-10 (paywall) under orders from Beijing to keep China growing through the global crisis. December’s lending letup appears to signal an easing of this trend.

Or it would, that is, if it hadn’t been offset by a steep rise in the sale of “wealth management products” (WMPs)—off-balance-sheet vehicles for GDP-boosting projects that are funded by bank customers. Deutsche Bank reports in a research note that WMPs issued by a sample group of Chinese banks rose 18% between last July and last September to 2.8 trillion yuan.

Though these figures almost certainly underestimate the actual size of the WMP load, they offer a sense of the trend. As China’s economy has slowed, its banks have found themselves in an increasingly tough spot. Official quotas limit how much they can lend to municipal borrowers, but they still face heavy pressure from local Chinese Communist Party officials to fund economic growth. The WMPs are the solution: repackaged corporate and municipal loans, often of dubious quality, that the banks keep off the books and sell to retail customers as high-yield investments.

The problem is that WMPs are flowing into projects that would previously have been too risky to qualify for loans, as the Financial Times explains. China is already littered with unviable infrastructure projects—for instance, its unsuccessful high-speed rail program, ghost towns and ambitious theme parks—built to keep people employed and growth high as the country pulled through the global financial crisis. After attempting to wean the economy off investment-led growth, last September, the government approved a rash of new projects such as railways, roads and airports. As Deutsche’s note observes, the rapid rise in new corporate financing last September and October was supported by “rapid sales of asset-backed WMPs [wealth products].”

Real estate is another example. Government efforts to cool the property sector have meant a scarcity of official lending. Enter trusts that are funded by WMPs, as in the case of a Chinese real estate developer from Hebei province that the Financial Times profiled, whose land-buying binge appears to be backed by WMPs, obscured through a complex deal structure.

Murky on many fronts

One reason for the explosive growth of these shadowy products lies in their opaque marketing. Reputable banks promote WMPs as high-growth alternatives to deposits, though they offer next to no information about how they earn these yields. As one China Construction Bank saleswoman told the FT, “It’s the investment banking department that manages these funds. Even we don’t know what they invest in.”

The government is not happy about this. Xiao Gang, a Bank of China board director rumored to be next in line to run China’s central bank, wrote a startlingly honest critique of WMPs in a state-run newspaper last year where he slammed risky WMPs, saying that they flow into “high-risk projects, which may find it impossible to generate sufficient cash flow to meet repayment obligations.”

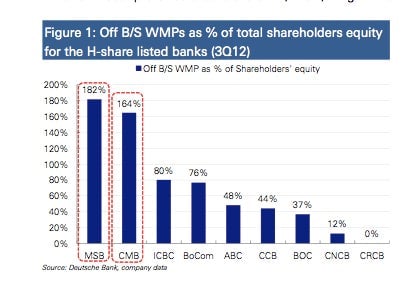

What would happen in that event is uncertain. As Wang pointed out, banks are vulnerable because WMPs may ultimately prove to be insolvent. Deutsche Bank has calculated the value of individual Hong Kong-listed Chinese banks’ off-balance-sheet wealth products outstanding relative to the size of their equity bases. (A bank’s equity is its net worth, minus all liabilities such as obligations to repay depositors.) The chart looks particularly scary in the cases of Minsheng Bank and retail-banking standout China Merchants Bank.

WMPs may also prove to be a massive risk to Chinese households in that, As Quartz has pointed out before, they resemble Ponzi schemes: New investors provide the money that pays back existing investors, since the companies whose loans make up the WMPs aren’t paying back that money themselves. The scheme can continue as long as banks collect still more deposits to stuff into the wealth products—until, that is, something causes them to unravel. And that may now be starting to happen.

Will WMPs melt down or melt away?

The first test case of what happens after a wealth product blows up began late last year, when a wealth product defaulted (paywall) for the first time widely reported. The lender that sold the product, the Shanghai branch of Huaxia Bank, initially said it was not on the hook for losses. After days of angry customers protesting outside its branch, Huaxia said it would offer “a reasonable solution,” according to the Wall Street Journal. Chinese politicians and regulators are still debating what to do next. They face an uncomfortable choice. A bailout would suggest all wealth products are guaranteed by the government not to fail. But allowing savers to lose money on the Huaxia product could spark a mass panic and a run on these types of funds.

Not everyone is concerned. Bank of America wrote in a January 8 note that while WMP defaults were “inevitable,” only a minority of these products were extremely high risk. Relying on Chinese government figures, BofA calculates that 20% or fewer of WMPs are backed by risky property loans, with the rest in lower-risk products.

But investment in wealth products may be set to slow for other reasons. According to Deutsche, the amount of money Chinese people are putting into their bank accounts is generally slowing, which could hint at a commensurate decline in demand for WMPs. Deutsche estimates that growth in the Chinese banking systems’ average deposit balance fell to 6.9%, year-on-year last September, down from 8.7% in December 2011. Deutsche also says that, while deposits are slowing, loans are again picking up, even if official data don’t reflect it. If the public becomes aware of this vulnerability in the banking system, Deutsche says, this will “deter investors from rolling over,” their wealth products (in other words, buying new ones).

It could also cause a run on WMPs that might spill over into deposits, particularly if more high-profile Huaxia-style controversies hit headlines. That would likely prompt the Chinese government to put the brake on wealth products—which could slow the Chinese economy. To prevent more Huaxia situations from occurring, Beijing is considering a crackdown on off-balance-sheet lending. BofA, too, thinks this is likely. And, as Deutsche wrote in a note published last month, a drop-off in this shadow funding would mean that its “positive effect on the economy could diminish.”

Even so, there’s the question of whether a crackdown would be effective, particularly considering how at odds the interests of the central government and local officials are. And to quote the old Chinese saw that many economists invoke when discussing Chinese bank behavior, “a strong dragon is no match for a serpent in its own lair.”