The huge and growing subprime debt time-bomb sitting inside China’s banks

China’s banks have not done too well in the past couple of years, due to a Chinese economic slowdown and fears about rising bad debts. But on Oct. 30 ICBC, China’s biggest bank, reported profits that came in ahead of investors’ expectations. Some analysts smell a change in the wind. China’s massive, state-owned banks, Macquarie’s Victor Wang suggested in a note to clients, have turned a corner. “We do not need to be super bearish for these money-making machines,” he said.

China’s banks have not done too well in the past couple of years, due to a Chinese economic slowdown and fears about rising bad debts. But on Oct. 30 ICBC, China’s biggest bank, reported profits that came in ahead of investors’ expectations. Some analysts smell a change in the wind. China’s massive, state-owned banks, Macquarie’s Victor Wang suggested in a note to clients, have turned a corner. “We do not need to be super bearish for these money-making machines,” he said.

But when the Beijing government unleashed its massive economic stimulus in 2009-10, China may have actually broken its banks for the long term. During the stimulus years, government officials told bankers to lend money to local governments for make-work projects that were probably unnecessary, leading to a pile up of doubtful municipal debts. So while ICBC on Oct. 30 reported a non-performing loan ratio (polite parlance for debts that may never be repaid) of a mere 0.87% of total assets, there is much suspicion that Chinese banks are not acknowledging the true extent of their soured loans. They may be “evergreening” (i.e., rolling over), reclassifying, or simply not recording them.

Chinese banks are growing at monster rates. But they are thinly capitalized. According to Fitch Ratings, Chinese banks’ asset bases expanded by $4.8 trillion from 2008 to the first half of 2012. If the growth spurt continues at the same rate, China’s banking system will have grown $14 trillion by the end of 2013, equivalent to the size of America’s entire commercial banking sector. Yet Chinese banks are among the least well capitalised in emerging markets (see chart below).

Likely bad loans are at least a problem bank analysts can count. They tend to add up local-government funding commitments, guess what percentage of each province’s projects will never become financially viable, and calculate the likely hole this will leave in lenders’ balance sheets. Some argue Chinese banks are not setting aside enough equity to shelter against future bad debts. Still, Beijing has already propped up some local government projects, suggesting it could remove bad debts from lenders’ balance sheets as they arise.

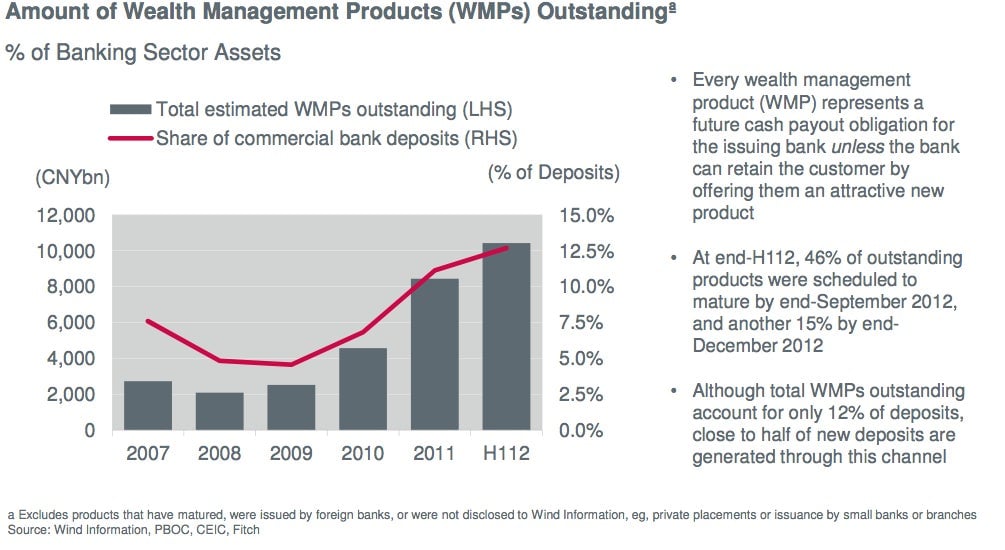

However, there is something analysts cannot measure: a ¥10 trillion ($1.6 trillion) potential liability from China’s secret, subprime corporate lending sector. In China, these are known as “wealth management products” (WMPs). They are investment products sold by banks to retail customers that promise high yields. In reality, they are ticking time-bombs of extremely unviable corporate loans—mainly to real estate developers and local governments—that the banks did not want or are not allowed to keep on their books. According to Fitch (chart below), the value of the outstanding WMP’s has reached ¥10 trillion. That is 16% of commercial bank deposits.

The subprime vehicles are a mechanism to offload bad debts. Wealth management products are how Chinese banks refinance dodgy borrowers. After the 2009-2010 lending binge, the Beijing government began imposing strict controls on bank loans to municipal borrowers and real-estate developers. This put Chinese bank managers in a bind. When they could not refinance an unsuccessful project because their lending quota for municipal borrowers was maxed out, they faced the project failing and becoming a bad debt. ”WMPs initially gained popularity as a way to offload loans after the 2009 lending boom,” said a note from Fitch Ratings in July.

Chinese business magazine Caixin explained it this way: ”Some banks, critics contend, slyly use funds raised by selling short-term, high-yield investment products to fill financial holes as soon as they appear—and before these holes show up on accounting books.”

But nobody really knows what the WMPs contain. The Beijing authorities have pressured banks to stop wrapping up dud loans into retail products. This, Fitch observed in the July note, meant banks started recording the credit-related assets inside the wealth management products as something else, such as interbank loans.

What is clear is that these subprime vehicles look very subprime. Xiao Gang, a board director of Bank of China, one of the country’s big four state-owned commercial banks, wrote a startlingly honest critique of WMPs in a state-run newspaper earlier this month. In it, he said:

China’s shadow banking sector has become a potential source of systemic financial risk over the next few years. Particularly worrisome is the quality and transparency of WMPs. Many assets underlying the products are dependent on some empty real estate property or long-term infrastructure, and are sometimes even linked to high-risk projects, which may find it impossible to generate sufficient cash flow to meet repayment obligations.

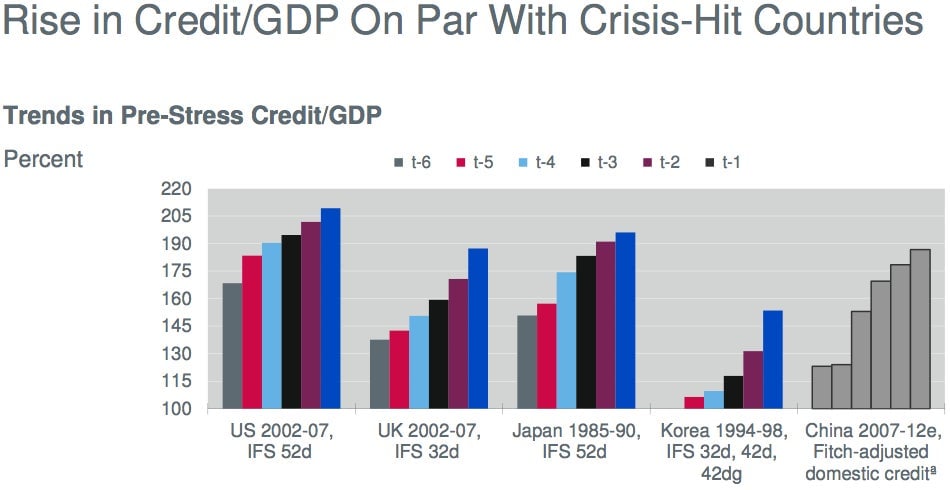

“The overriding point about these products is that no-one can say with any certainty what is in them, so it is hard to calculate exactly what damage they may do to the banks,” Fitch Ratings senior analyst Charlene Chu said in an interview. And Merrill Lynch analyst David Cui warned in a note to clients last week.”It appears to us that wealth management products (WMPs) [are] increasingly assuming the role of the CDOs in China”—CDOs, of course, being the collateralized debt obligations that allowed investor money to pour into the subprime mortgage market in the US, inflating the housing bubble and seeding the 2008-09 financial crisis. Indeed, the ratio of credit to GDP over the past few years in China looks eerily familiar:

What’s more, the banks may be lending to their own subprime vehicles (which already contain their own bad loans). Fitch wrote in July:

“In 2012, a growing share of funds raised through WMPs have been invested in interbank assets, giving the impression that liquidity and credit risk of products has declined. However, this can be misleading. Many interbank assets of Chinese banks actually represent corporate credit disguised as interbank claims. Meanwhile, banks occasionally conduct “interbank” transactions with their own WMPs, meaning that some of these assets could be claims on themselves that are not backed by any real cash flow.”

And the WMPs are run like Ponzi schemes. The banks manage the cash that is paid into their various products in large pools. In other words, investors’ funds do not remain attached to the security they bought. So the WMPs themselves do not have claims over any particular loans or securities. ”New investors’ money goes into the pool, and money from the pool is used to pay existing investors’ returns,” explains Patrick Chovanec, associate professor at Tsinghua University’s school of economics and management in Beijing.

This makes them look like Ponzi schemes.

Also, the WMPs themselves do not have a legal claim over any particular loans or securities. ”And the returns investors get have nothing to do with the performance of the products’ underlying investments or loans, which in many cases are probably not generating cash,” Chovanec says.

There are various ways the sub-prime products could blow up. First, corporate borrowers could simply go under, taking the depositors’ money with them. The products could also fail because the Ponzi funding dries up. As Cui outlined in his note: ”the music is still playing and it’s uncertain how long it may last (it will largely come down to when buyers stop buying WMPs, fearing a loss of principal)”.

There is also the matter of lopsided funding structures. Investors mostly commit cash for less than three months. But the WMPs are often funding projects that have ongoing, long-term needs for cash. As Cui explained further in his note, WMPS ”can be invested in illiquid assets and are probably funding many infrastructure, property and other risky projects directly or indirectly”. If the wealth management funding dries up, the underlying investments could go bust.

Similarly, Fitch wrote: “Fitch Ratings has frequently raised concerns over the strains that WMPs place on banks’ funding and liquidity—due to the increased mobility of depositors and the pressure to meet cash payouts at maturity.”

Chinese banks say the wealth management products are nothing to do with them. They are just managing funds on behalf of investors. This may sound familiar to anyone who observed the subprime lending debacle in the US. Chinese banks set up wealth management products, invest the assets drawn from customers into corporate loans, and then pay investors out of the profits they make from the loans. “Banks don’t think they are liable for defaults as they are only managers of the products,” Cui wrote.

But the banks will likely have to refund retail investors if the WMPs explode, Fitch’s Chu clarified in an email, saying:

Our view is that banks have very limited room to impose losses on investors if the products go bad, in large part because the disclosure is so poor. In many cases, the precise assets are never disclosed, so the bank has no way to prove to investors that the assets are nonperforming. For this reason, we believe many of the products should never be allowed to be moved off-balance-sheet in the first place.

Chinese banks should also tell investors whether they are buying each others’ WMPs—whether for the yield or to help each other disguise corporate debts as interbank transactions—and how big their exposure is. But such detail is never forthcoming. As Fitch wrote in July: ”Banks face no public reporting requirements, there is no centralised catalog of issuance and WMPs still lack unique identifiers to trace them.”