Of all the creatures in the world, the Irukandji is among the most fearsome. It’s about as easy to spot as a floating sliver of cellophane. But a mere human brush with these tiny creatures causes hearts to fail and blows out blood vessels in the brain. Even those that survive are racked with suffering so extreme that it’s been given its own name (“Irukandji syndrome”). Fortunately for most, these little guys don’t travel outside a shred of the ocean in northern Australia.

Or, at least, they don’t yet. However, new research suggests that while the ocean’s rising acidity might keep them up north, warmer coastal waters could help Irukandjis reproduce further and further down the continent’s east coast—and smack into some of Australia’s biggest tourist hotspots.

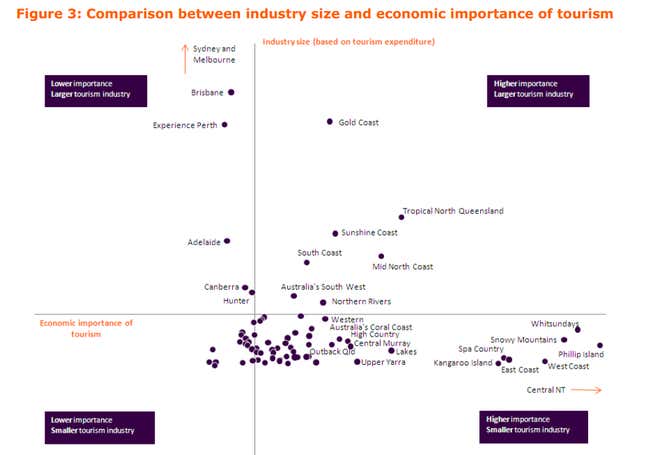

That could deal a big blow to Australia’s tourism industry. Queensland generates a sizable chunk of Australia’s tourist dollars. In 2011, tourists spent A$26.5 billion ($25.2 billion) in Queensland (pdf, p.20), 25% of Australia’s total tourism consumption.

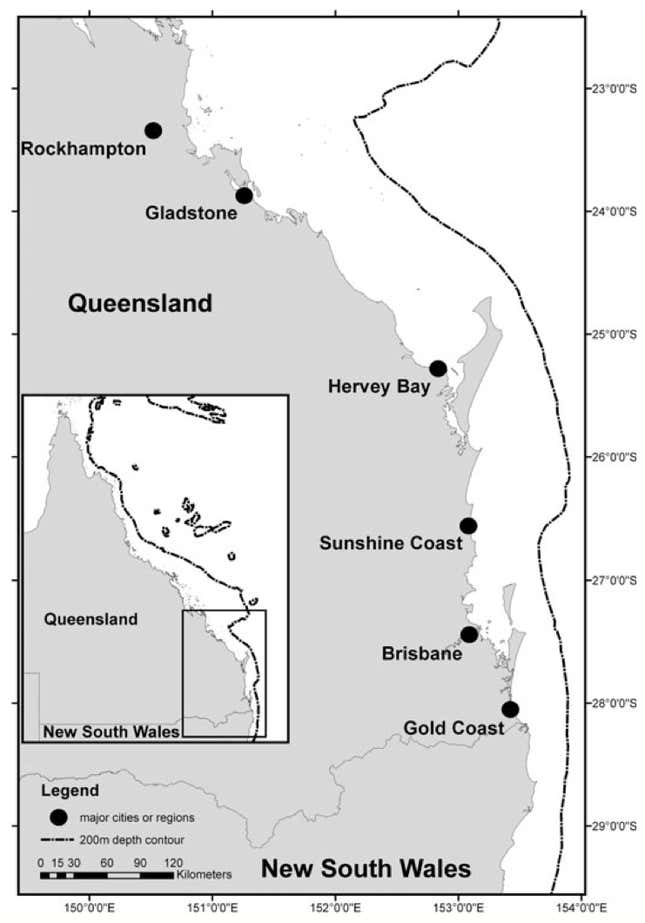

In 2007, the most recent year of available data, the Sunshine Coast and the Gold Coast generated a combined 26% of Queensland’s total tourism output (pdf, p.22). Counting Brisbane, an international hub of regional tourist traffic, that jumped to 88% of Queensland’s tourism revenue.

In the context of Australia’s lethal menagerie, the Irukandji’s southern drift might not seem like a big deal. After all, Gold Coast surfers already have to worry about great white sharks, and that hasn’t put a dent in tourism. Even the threat of another deadly jellyfish, the box jellyfish, has been manageable. That said, northern Australia has had to put up nets during peak swimming season to protect beach-goers.

But those nets are likely too coarse to work on Irukandjis, says Kristen Rathjen, an ecologist who worked on the study. “These guys are so small [that] when they actually strobilate [meaning “hatch,” in a sense] into a swimming organism they’re about the size of your pinky fingernail,” she tells Quartz. “[They] can pass through coarse nets and you’re not going to see them.”

If coastal waters become more acidic, these fears may prove unwarranted. But even if the Irukandji confines its mating to its current habitat, there’s another factor that could sweep it southward, say the study’s authors. Climate change has strengthened the East Australian Current (EAC)—a huge swath of warm water that acts as a sort of oceanic highway (see: Finding Nemo)—sending balmy tropical waters streaming as much as 350 km (218 miles) further south than it did 60 years ago, says Shannon G. Klein, the lead researcher.

Klein also says the team’s findings suggest that warming seas could widen the Irukandji’s reproductive range in other parts of the world where they are found. Where might that be? Thailand, Florida, Cuba, the Gulf of Mexico, Hawaii, and possibly the Caribbean.