The swift uptick in Chinese corporate debt is worrisome, especially in light of the country’s economic slowdown. But the bigger and more troublesome problem lies with China’s retail investors—one that by itself could bring down the country’s entire financial system.

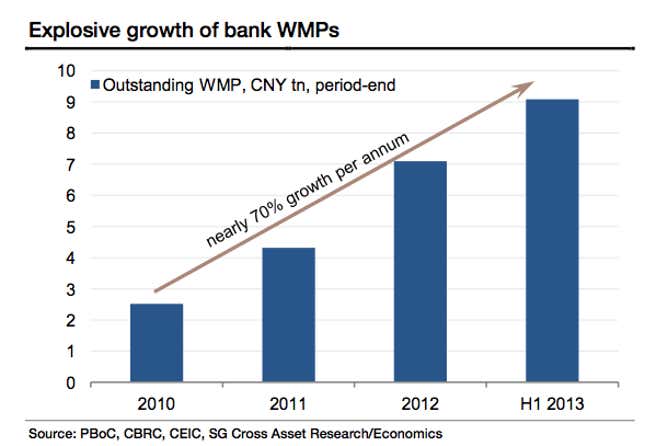

Next year, some 2.6 trillion yuan ($427 billion) in Chinese corporate debt will mature, reports Bloomberg—19% more than in 2012. The lagging economy increases the likelihood that a good few companies will be caught without the money to pay up. But then there’s the $10 trillion yuan ($1.6 trillion) (link in Chinese) in wealth management products (WMPs) that Chinese banks have now created, 90% of which matures in less than one year. (WMPs essentially securitize longer-dated corporate debt and off-balance-sheet loans, allowing banks to make money from retail customers without issuing loans.)

The Chinese government’s ownership of the biggest banks gives it tremendous control over the official banking system, allowing it to step in before a company defaults. It has much less control, however, over “shadow lending,” credit channels undocumented on bank balance sheets, which fund companies that are too shady or too risky for banks to give official loans.

Most of that $1.6 trillion in WMPs is tied to assets financed through shadowy channels. These nine charts explain how that number got so big, and why, if a Chinese financial crisis happens, WMPs will be one of the likeliest triggers:

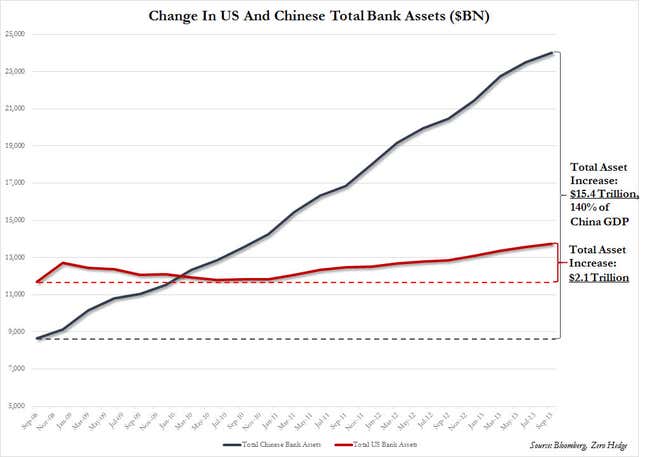

China lent its way out of the global financial crisis.

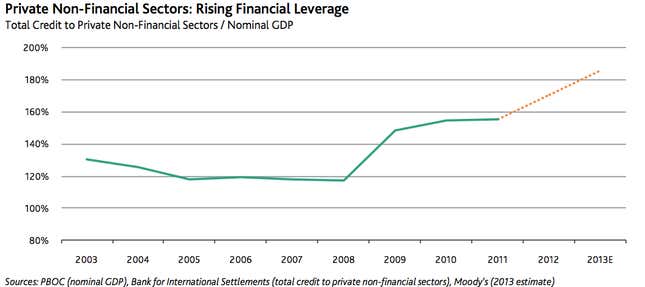

Corporate debt has hit unprecedented highs, as a report out from Moody’s today explains.

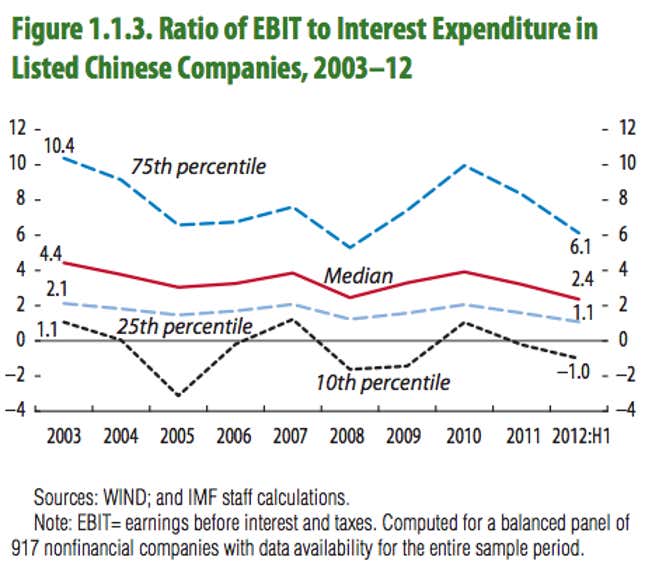

But the economy is slowing. Less growth means more and more companies aren’t making enough to pay back their debts.

So they take out more loans. How? Via China’s shadow lending system, which takes place off bank balance sheets. That explains why WMP issuance has grown from 4.6 trillion to 10 trillion in less than two years.

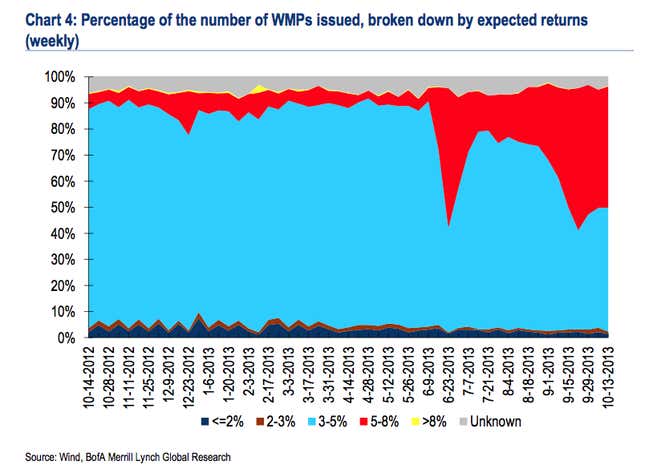

As corporates get increasingly starved for cash, WMP rates have surged. Retail customers are loving this since they can earn a lot more on those than on bank deposits, which the government sets at artificially low rates.

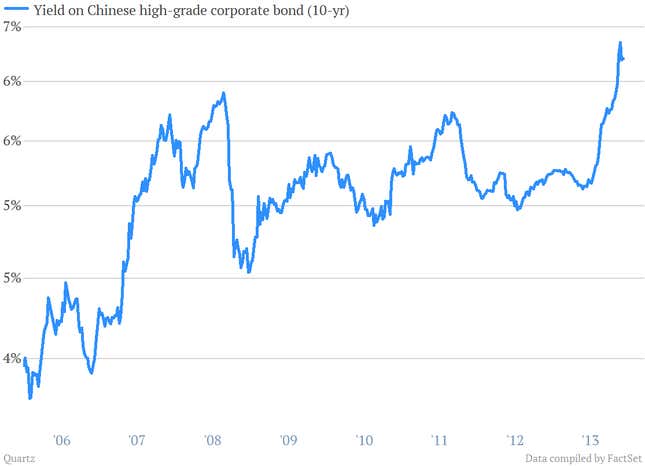

That hunger for cash is showing up in the corporate bond market now.

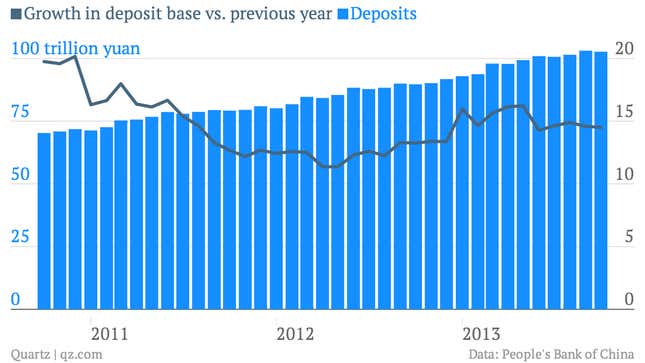

And since retail investors prefer buying WMPs to depositing cash in banks, banks are losing their deposit bases. Compared with banks from other major countries, Chinese banks are desperate for deposits.

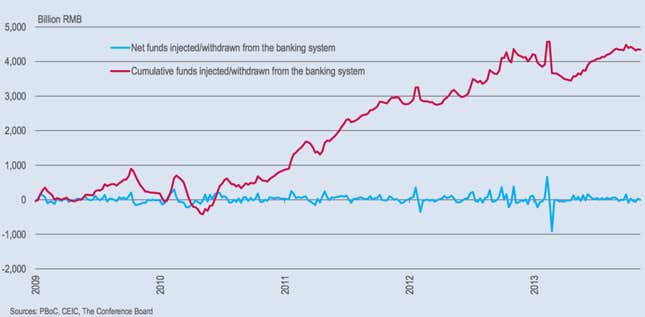

As cash dries up, the central bank has to pump more and more into the financial system to keep money flowing and rates from spiking.

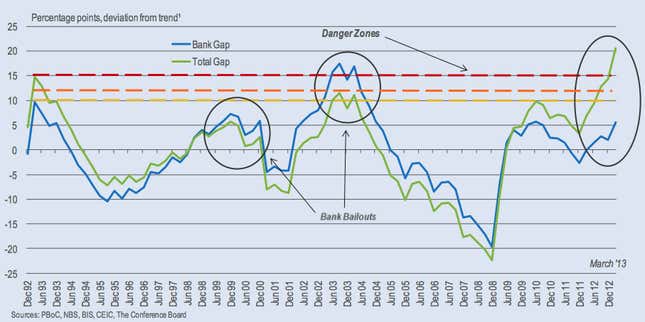

The result: China’s shadow lending has driven outstanding credit beyond historically catastrophic levels, as this chart from The Conference Board shows.

One way of measuring the likelihood of a financial crisis in a given country is to look at its credit-to-GDP “gap,” that is, how a country’s credit-to-GDP ratio differs from its long-term trend, according to research by the Bank of International Settlements (pdf). In the chart above, the Conference Board traces this metric for official lending (blue line) and all lending, including shadow lending (green line). As you can see, shadow lending—much of which is what’s repackaged as WMPs and sold on to regular Chinese households—has pushed China into the danger zone.

If slowing growth causes a rash of WMP defaults, causing households to pull their money, a huge source of liquidity will evaporate that has been keeping otherwise insolvent companies from going broke. The higher that green line climbs, the likelier that possibility becomes.