In the ”which city is better” rivalry, Shanghai has always claimed one huge advantage over Beijing: its air quality. No more. Last week, toxic haze descended on the city, prompting authorities to warn children and seniors to stay indoors and flights to be grounded.

But even if their pollution levels hadn’t before indicated it, coal emissions have been killing Shanghai residents prematurely for a while now. In fact, Shanghai’s 22 coal plants cause 4,370 premature deaths a year, according to an interactive map by Greenpeace, a non-governmental organization. Beijing’s 10 plants cause only 1,004 deaths a year. And while the capital’s most lethal plant was responsible for 442 premature deaths in 2011, a coal plant in northern Shanghai kills 627 people a year.

Shanghai and Beijing death rates are a drop in the bucket, though. The map, which is based on the World Health Organization’s analysis of mortality rates attributable to coal emissions, shows that Chinese coal plants caused a combined 257,000 premature deaths in China in 2011. Here’s what the nation looks like:

Burning coal gives off sulphate and nitrate, which make up 80% of the particles in Shanghai’s PM2.5, the common measure of fine particles in the air that, when breathed, lodge far enough into the lungs to enter the bloodstream. These are supposed to be scrubbed out by emissions controls. However, in order to cut costs, power plants often uninstall scrubbers after inspections.

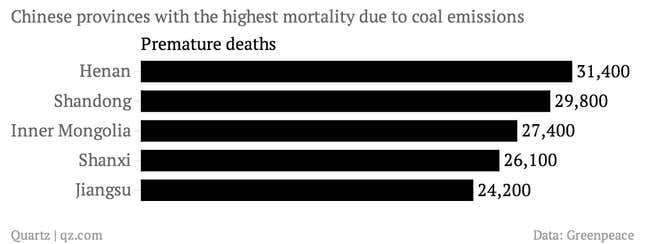

The provinces with the highest number of premature deaths are generally known for their booming use of coal. Shandong, Shanxi and Inner Mongolia, for instance, consumed 32.7% more coal in 2011 than in 2006, says Greenpeace. Those three provinces burn nearly one-third of the nation’s total—around the same amount that the US consumes.

The WHO study that map is based on found that around 1.2 million Chinese people died prematurely from air pollution of all types, including other industrial emissions and vehicle exhaust fumes. So clearly cleaning up coal isn’t the only answer. But it will be a good place to start.

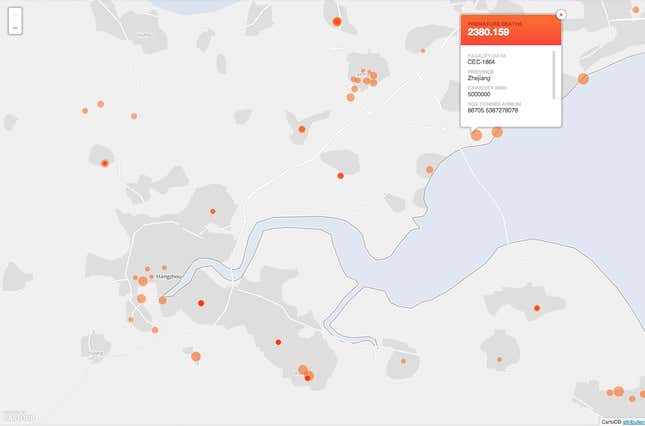

Though this study is based on 2011 data, and could therefore have changed in the last two years, it suggests that local governments in wealthy areas have a long way to go. For example, Jiangsu is China’s wealthiest province; Shandong too is relatively rich. The most lethal single plant in all of China is in Zhejiang, China’s third-richest province:

The surprising density of coal plants in posher areas of China also means that relocating coal power stations from wealthier areas could make a big impact. That bodes well for local governments in Beijing, Shanghai and other wealthier areas, which have stepped up efforts to curb coal consumption this year.

Those campaigns so far center mainly around cleaning up skies around wealthier urban areas—places where residents might organize outrage more effectively than those in poor areas. Leaving aside the issue of fairness, a mismatch of water resources is one reason this is a potentially catastrophic idea, as we discussed here and here.