The Chinese central government may be gearing up for its first comprehensive attempt to take control of the trillion-yuan-plus industry around extending off-balance-sheet loans, known as “shadow banking.” And this could have all sorts of destabilizing knock-on effects.

The sign the government wants to act comes in a set of guidelines known as Document No. 107, which was leaked to the Chinese media today (link in Chinese). What they boil down to is that the government wants to clean up debt.

And there’s a lot of debt. The government weathered the global downturn by lending like crazy to juice growth through investment, often in projects that won’t make a return for years, if ever. The slowing economy has left more and more companies insolvent, paying off existing debts with shadow loans (more on that here and here).

Which is why it won’t be easy, argues Wei Yao, an economist with Société Générale. ”This development, if confirmed, [suggests] the central government is (very) serious about deleveraging…,” she writes. “The short-term impact on economic growth will almost certainly be unpleasant.”

Here are some reasons why if the guidelines are implemented, 2014 will likely see a surge in cash crunches and even defaults:

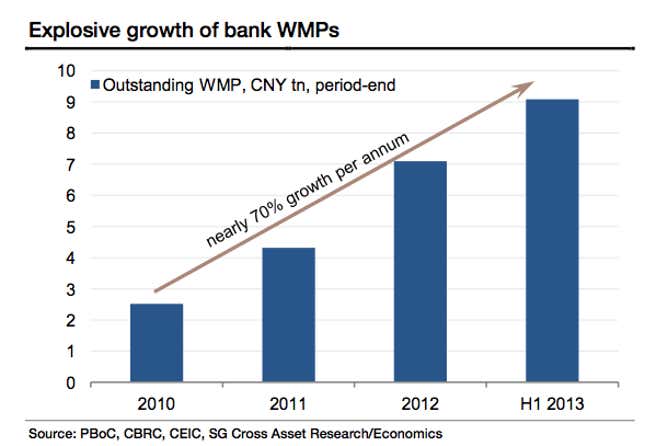

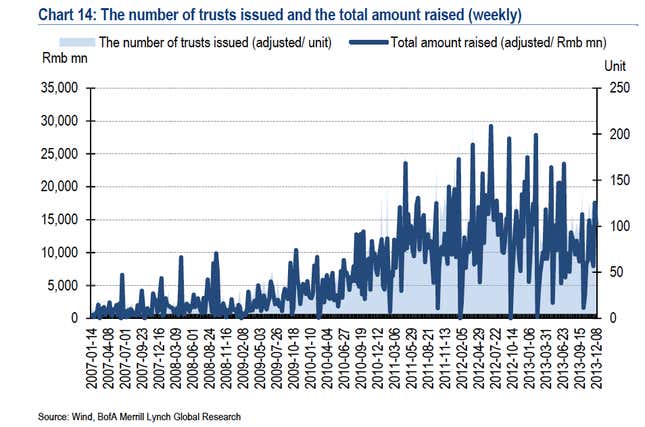

- The rules are pretty tough on two big sources of shadow lending: WMPs and trusts. Wei Yao of SocGen explains that banks wouldn’t be able to issue wealth management products (WMPs)—retail investment products that often fund insolvent companies at high interest rates—tied to certain dodgy assets. Trust companies may now have to pony up capital against loans.

- Local governments depend heavily on funding via WMPs and trusts. In order to raise money for GDP-juicing projects, local government set up what are called LGFVs—local government financing vehicles. Shadow credit taken out by LGFVs has been a huge force driving up local government debt, which hit 17.9 trillion yuan ($3 trillion) as of June.

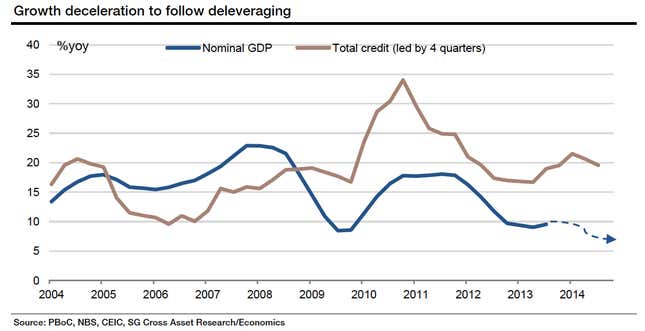

- Growth will slow sharply. It takes more and more credit to create economic growth these days. And since clamping down on shadow channels means less credit, China’s GDP growth will drop, assuming all other things remain equal:

- That means tighter and tighter liquidity. As insolvent LGFVs and state-owned enterprises have grown more desperate for money, the entire system has become vulnerable to cash crunches. That’s why any time the central bank holds back liquidity, rates have leapt, and banks have stopped lending from each other. Document No. 107 means even scarcer funding, which likely means more cash crunches like those in June and December last year.

- Tightening up WMPs and trusts will also spur a rash of defaults. Since many of these projects don’t actually generate enough money to cover existing debts, LGFVs rely on shadow loans for stopgap funding. Cut that, and some of these will default.

- That could create financial panic among savers. Because there’s never been a publicized default on the loans that underlie WMPs and trusts, no one really knows who—banks, the central government or investors—will have to swallow the inevitable losses, as we recently discussed. If investors are left on the hook or even sense that uncertainty, investors and depositors could pull their money.

It all comes down to enforcement, however. The banking industry has consistently worked around past government crackdowns on shadow channels.

Plus, Document No. 107 actually applauds shadow banks for their “positive role in serving the real economy and enriching investment channels for ordinary citizens,” as the Financial Times reports (paywall). That hints that it might not want to regulate the industry too heavily, as doing so would crimp growth. If that’s the case, 2014 won’t be much wilder than last year. 2015 though? Absolutely pear-shaped.